~~ recommended by desmond morista ~~

Introduction by desmond morista: The ruling class of the U.S. is now faced with a difficult set of problems both internally and overseas; and concurrently there are some internal struggles going on between the various U.S. ruling class factions as to where to commit the large, but still finite, resources of the U.S. military. Let's have no doubts -- the strongest and most nimble faction is, as always, the various forces of Zionism. But seeing as the situation in Israel and Gaza is more-or-less under control right now, in a manner favorable to the far-right rulers of Israel and their domestic U.S. allies, these other U.S. factions currently have more leeway to pursue other agendas.

The situation in Venezuela is telling in that this is the first serious challenge to the strict control that the U.S. has placed over the various societies of the Western Hemisphere since at least about the 1870s or 1880s. The famous Monroe Doctrine was first elucidated in 1823 and was actually a hollow statement for decades. The Royal Navy of the British Empire was the main force that maintained conditions favorable to the Ruling Capitalists of the day, the British Empire being the leading force with the French, Dutch, Spanish and Portugese Empires operating in lesser strength. The U.S. rulers were primarily interested in conquering and purchasing their way across North America, their main interaction with Latin America during the mid 1800s was The Mexican War in which the northern half of Mexico passed under U.S. control.

But by the 1880s the U.S., that passed up the U.K. in industrial capacity during the 1880s and 1890s, and the U.S. rulers began to build a Blue Water Navy and to otherwise flex their muscles on the world stage. John Mearsheimer has pointed out that the U.S. is unique among all the empires in history, and of all the Great Powers of the current day in that it faces no sort of serious competition, threat to, or disruption of its business and resource extraction operations in its hemisphere. This is basis of the famous “backyard” reference to places like Venezuela. Just as the Roman Empire referred to the Mediterranean as Mar Nostra (Our Sea), the U.S. rulers think of the Caribbean Sea as their “American Lake”. This favorable position for the U.S. ruling class is now threatened for the first time since the 1850s; as China has made large investments in Venezuela to modernize and repair their petroleum extraction and transport operations.

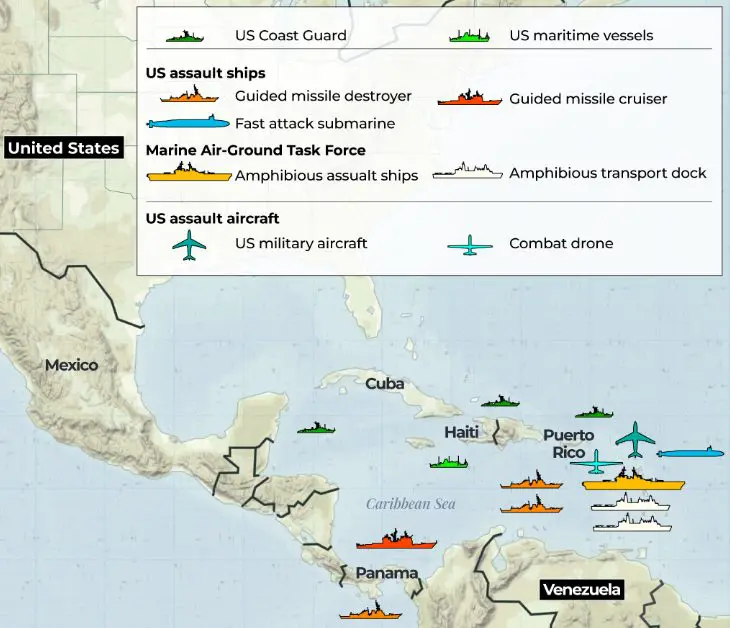

The question of controlling Venezuela's oil is certainly a major issue as well, the country is now rated as having the largest proven reserves of oil on Earth. This situation is shown graphically in the map and modified pie chart here below.

The total petroleum reserves of Venezuela are much higher (about 9 times as high) if we include the Orinoco Tar Sands oil which has an estimated quantity of 2.3 TRILLION Barrels. Those Tar Sands are very similar to the Athabascan Tar Sands in Alberta, Canada (I don't know if Canada's proven reserve figures include the Athabascan Tar Sands or not). Koch Industries has a huge refinery south of Houston on the Texas Gulf Coast purpose built to extract usable petroleum from semi-processed Venezuelan Tar Sands material (called Bitumen).

The struggle, during the last couple years of the Obama Administration and the first year of the first Trump Regime, over pipelines in South Dakota (the Dakota Access Pipeline) and fights in Minnesota (the Line 3 Expansion) were all partially or totally over attempts to provide pipelines to move Bitumen from Alberta to markets and refineries in the U.S. The Tar Sands are, in reality, horrific sources of energy that cause significant damage to the environment and don't yield much energy after the huge amounts of energy expended to mine, process, and move the material. The standard measure of how much energy is actually produced is called net Energy Return on Investment (EROI). In the early days of the petroleum industry that stood at about 39 barrels of oil equivalent produced for each barrel of oil expended. A level of 4 is considered the benchmark for a generally and an economically viable project. Tar Sands / Oil Sands are at or below that cut-off level.

As for the viability of an invasion or some other military venture to try to remove Maduro and/or to replace the left-leaning government of Venezuela with a reactionary / fascist regime, more amenable to Trump and his backers and handlers, time will tell. The Russians who have supplied military equipment to Venezuela, and the Chinese who have no doubt supplied some military equipment and who have certainly invested a significant amount of money in Venezuela's oil industry, are both reluctant to challenge U.S. or U.S. allied mercenary / proxy forces in Venezuela. A potential U.S. involvement in an attack on Iran or further greater efforts in Ukraine would be entirely another matter, and the balance of forces and technologies no longer overwhelmingly favor the U.S. The Zionists hold significant sway over Trump Regime so we cannot rule out an attack on Iran, however disastrous that might be for the U.S. in general.

1). “Max Blumenthal on the war on Venezuela”, Nov 2, 2025, Max Blumenthal delivers a lecture to an audience at the Community Church of Boston, Community Church of Boston, duration of video 41:34, at <

2). “Max Blumenthal: Venezuela Invasion - A Predictable Disaster”, Nov 5, 2025, Glenn Diesen interviews Max Blumenthal with questions about the developing situation in Venezuela, Glenn Diesen, duration of video 32:52, at <

3). “A Geopolitical Analysis of the Imperialist Buildup Against Venezuela: A Conversation with Ana Esther Ceceña: Natural resources and strategic alliances are important to understanding why Venezuela is in the eye of the storm”, Oct 11, 2025, Cira Pascual Marquina interviews Ana Esther Ceceña, Venezuela Analysis, at < https://venezuelanalysis.com/interviews/a-geopolitical-analysis-of-the-imperialist-buildup-against-venezuela-a-conversation-with-ana-esther-cecena/ > (reposted by MROnline, Oct13, 2025, “A Geopolitical Analysis of the Imperialist Buildup Against Venezuela: A Conversation with Ana Esther Ceceña”, MROnline, at < https://mronline.org/2025/10/13/a-geopolitical-analysis-of-the-imperialist-buildup-against-venezuela-a-conversation-with-ana-esther-cecena/ >)

A Geopolitical Analysis of the Imperialist Buildup Against Venezuela: A conversation with Ana Esther Ceceña

Ana Esther Ceceña is a Mexican economist and geopolitical analyst known for her expertise in Latin American affairs. She serves as the director of the Latin American Observatory of Geopolitics at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). Her scholarly work explores the dynamics of power, sovereignty, and resistance, with a focus on strategic resources and the global capitalist system.

In this interview, carried out in Caracas during the recent “Colonialism, Neocolonialism, and the Territorial Dispossession by Western Imperialism” (October 2-4), Ceceña offers an incisive analysis of Venezuela’s role in contemporary global geopolitics. She discusses the implications of the recent U.S. military escalation in the Caribbean, the strategic significance of Venezuela’s resources, and the broader geopolitical conflicts involving major global powers. Ceceña also reflects on the resilience of the Venezuelan people and their struggle for sovereignty amidst external pressures.

A Pentagon leak published recently by Politico suggests that Washington could be pivoting away from China toward “protecting the homeland and the Western Hemisphere,” effectively reviving the old Monroe Doctrine under new terms. How do you read this apparent strategic turn?

The United States has long identified four countries—Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran—and a non-state entity—Al-Qaeda and its derivatives—as its main enemies. These remain the strategic adversaries for the U.S.

The U.S. has been following this program closely, primarily confronting China but also engaging via proxy conflicts with the others: a war against Iran through Israel (which recently escalated to direct attack) and a war against Russia through Ukraine.

However, to confront these strategic enemies, Washington needs to control the American continent. That is why we now see the hemisphere becoming its main priority. Latin America, with its natural resources and geographic advantages, including its relative insularity, has always been central to U.S. military strategy. However, a period of intensification is opening up. Their idea is that as long as the U.S. controls the Americas, it effectively cannot be attacked on its territory. It’s as if the U.S. were surrounded by a moat.

However, the correlation of forces in the continent has been changing: China, Russia, and even Iran—three of their five so-called enemies—are already in the region. China is making large-scale commercial agreements and infrastructure investments with most countries in the hemisphere, building ports and establishing trade routes. China is already here, competing in the US’s own “backyard.”

Meanwhile, Russia provides military support to Venezuela and maintains a strong presence in Cuba. This is a huge problem for the United States, particularly because Russia now has more advanced military technology than the U.S. in many respects. Its missile production is faster, cheaper, and more efficient, while the U.S. military industry is lagging behind.

The presence of these powers in the Americas weighs heavily on Washington.

Another key reason for the U.S. focus on the continent is economic: without the oil, minerals, and even the labor force of Latin America, it simply cannot sustain itself. It needs territorial footholds and access to extract the region’s resources for its own reproduction.

Alongside the intensified imperialist military buildup against Venezuela, the United States has just issued a license allowing Trinidad and Tobago to exploit offshore gas in Venezuelan boundary waters, while Exxon’s illegal drilling in disputed Essequibo waters continues unabated. How do these moves fit into the broader campaign of resource plunder and military pressure against Venezuela?

It’s not entirely clear what the White House is planning, but it appears to be preparing for multiple scenarios. Positioning military assets around Venezuela is strategic for controlling international transport routes: from there, U.S. forces could intercept vessels and effectively impose a total blockade both inward and outward, cutting off the country’s ability to export its resources. Such a move would have devastating consequences for Venezuela’s economy.

In the Essequibo case, the U.S. is already deeply involved through ExxonMobil, which continues extracting oil despite the ongoing territorial dispute. Washington will not give up that foothold. Even as litigation drags on, Exxon is pumping and storing as much as possible. At the same time, the U.S. may seek to undermine Venezuela’s own production capacity, potentially by targeting refineries or other strategic facilities.

It’s still not clear how this strategy intersects with Chevron’s operations in Venezuela. However, as one of the United States’ flagship oil corporations, Chevron’s continued presence serves U.S. strategic interests and even supports supply chains linked to the Essequibo extraction. Yet any escalation or attack on Venezuela’s oil infrastructure could jeopardize those same arrangements, exposing contradictions within the U.S. approach.

As for the natural gas exploitation along the maritime border between Trinidad and Venezuela, we’ll have to see how the situation develops. The entire regional oil landscape is extremely tense: frictions are mounting with Brazil, and Mexico is also facing intense pressure from Washington.

Mexico extracts oil but lacks the capacity to refine it, so most of its crude ends up in the United States, both through legal channels and via an extensive black market. In fact, a major scandal has erupted over the illegal siphoning of oil from pipelines, which we call “huachicol” in Mexico. Along transport routes, criminal networks tap into ducts to extract crude that is later sold, often across the border. The scale of this illegal trade now surpasses that of legal flows, revealing a highly organized operation with clear counterparts on the U.S. side.

Going back to Venezuela, however, I want to highlight that it represents a problem for the U.S. that surpasses oil: Venezuela is a sovereign country with a transformative project and a combative people. That’s of huge concern to the U.S.

That was precisely my next question. The imperialist aggression is often reduced to Venezuela’s vast oil reserves, but in reality, what’s at stake goes far beyond natural resources. There’s also a political project that poses a challenge to U.S. hegemony. Could you tell us about that?

Venezuela’s resources go far beyond oil. It has gold, access to the Amazon basin, and strategic proximity to the Panama Canal. However, Venezuela’s most extraordinary resource is the consciousness of its people.

Venezuela remains a profoundly Chavista country, marked by geopolitical consciousness and a collective commitment to defending its sovereignty. The role of the military here differs fundamentally from that in countries like Mexico: it is not an invasive force but a people’s army. Many have joined the armed forces as a conscious act of popular defense of national sovereignty. This unity between the people and the military is integral to a broader social and political project that continues to forge its own alternative path.

The experience of the communes, for example, is crucial. There’s nothing like this level of authentic popular democracy anywhere else. Venezuela poses a huge challenge to the United States because it’s not only resilient but also inspiring and it could be contagious.

Venezuela is not isolated. Across the world, new anti-colonial movements such as those in the Sahel are rising. There, people once considered powerless are now standing up. If they can, why not others? Venezuela is part of this broader tide of popular emancipation. At the same time, international initiatives like BRICS are charting new forms of cooperation among nations that challenge the existing global order.

Would you agree with those who argue that U.S. imperialism is facing a crisis of hegemony?

Absolutely! The U.S. is in serious trouble. The loss of terrain in economic terms is most obvious: they aren’t able to bring manufacturing back, and the U.S. dollar is no longer the exclusive global currency. In short, if the United States is acting somewhat erratically, that’s because it is struggling to maintain global political and military dominance.

Is the U.S. also losing ground militarily?

Yes, significantly. As I mentioned before, Russian military technology is now superior in many respects, and China, North Korea, and Iran have also developed powerful capabilities. Each excels in different areas, and together they form a formidable bloc. Also, their armies are much larger than the U.S. China’s recent military parade revealed a massive, technologically advanced force.

The Bolivarian Government, which broke diplomatic relations with Israel in 2009, has been steadfast in its solidarity with the people of Palestine, and it has not hesitated in calling the genocide by its name. How do you situate the genocide in Gaza within this global geopolitical context?

There’s a global competition underway for control of key trade routes for oil, resources, and goods. A central factor to explain what is going on in Palestine is the U.S. proposal for a commercial corridor linking India to the Mediterranean via West Asia, designed to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative. This corridor would pass through Israel and necessarily across Gaza, making Gaza strategically important as a potential alternative to the Suez Canal.

Additionally, Gaza’s coastal waters contain significant gas deposits discovered relatively recently. Since then, Israel has sought to reduce Gaza’s maritime boundaries, while British companies, backed by the UK government, have moved in to exploit these resources. That’s one reason for Britain’s complicity in the ongoing conflict.

Palestinians are struggling against a colonialist project, but they are also dealing with direct imperialist interests: natural resources and strategic geography. And once more, we see the same actors: the big corporations and the main powers of the “collective West,” namely the U.S., Britain, and occasionally France or Germany. Israel serves as the regional platform for their operations, doing the dirty work of territorial cleansing.

Another largely ignored case is Sudan, on the Red Sea. It’s also being torn apart by war and mass displacement. Sudan’s location is crucial geopolitically and for trade routes and, like Venezuela, it’s rich in oil.

When you look at an oil reserves map, you can see a clear belt stretching from Central Asia to West Asia through Africa and reaching Venezuela… and where are most conflicts unfolding? Along that corridor. Venezuela sits at the western end of this chain.

Going back to Venezuela, how far do you think U.S. imperialism’s current military escalation will proceed?

It’s difficult to say. Washington is now threatening not only air and naval operations but also potential ground incursions. A direct invasion, however, would entail full-scale war, which U.S. forces are unlikely to undertake. More feasible are surgical operations such as attacks on oil facilities or key infrastructure.

They have already attempted regime-change operations similar to the Noriega-style “extraction” of Maduro, but these efforts failed. Venezuela’s high level of organization makes such actions extremely difficult. That said, they are likely to continue attempting smaller-scale incursions along the coast.

The situation isn’t easy for Venezuela, as it cannot rely fully on support from the continent, which is fragmented. Nevertheless, the country retains allies and, most importantly, it has the strength of its people, who are organized, actively participate in the militia, and are prepared to defend the nation.

4). “Putin's Nukes STUN Trump, Oreshnik Missiles to Venezuela? Larry Johnson & Col. Wilkerson JOIN”, Nov 5, 2025, Danny Haiphong discusses various issues of the overseas critical areas with Larry Johnson & Col. Wilkerson, Danny Haiphong, duration of video 126:48, at <

5). “Will the US Attack Venezuela? Solidarity activist and analyst Roger Harris takes stock of the rapidly escalating US military threats against Venezuela”, Oct 10, 2025, Roger Harris, Venezuela Analysis, at < https://venezuelanalysis.com/opinion/will-the-us-attack-venezuela/ > (reposted by MROnline, Oct 25, 2025, “Will the US Attack Venezuela?”, MROnline, at < https://mronline.org/2025/10/25/will-the-u-s-attack-venezuela/ >)

6). “The Looming Attack on Venezuela: What does it signify”, Sep 3, 2025, Hindustan Times hosts Jeffrey Sachs for statement / interview, Hindustan Times, duration of pertinent part of video is the initial 6:32, at <

7). “Ben Norton: The Shocking Truth About America’s Plans for Venezuela”, Oct 21, 2025, Cyrus Janssen interviews Ben Norton about the background to the likely massive U.S. attack on Venezuela, Cyrus Janssen, duration of video 47:08, at <

8). “My Interview with Caleb Maupin: Will Venezuela Become the Next Iraq?”, Oct 22, 2025, Foadebate host interviews Caleb Maupin, Foadebate, duration of video 28:48, at <

9). “Venezuela Tar Sands”, n.d. (appears to be from about August 2018), anon, Global Energy Monitor WIKI, at < https://www.gem.wiki/Venezuela_Tar_Sands >.

Venezuela Tar Sands

Strategic Significance

Discovered in 1979, Venezuela's Orinoco tar sands hold an estimated 2.26 trillion barrels of oil but development remains in an early stage due to the country's political turmoil, insufficient infrastructure, and insufficient foreign investment. Using current technology the Venezuelan government estimates there are 316 billion recoverable barrels of oil, according to Bank Track.[1] More recently, the US Geological Survey placed the mean estimate of recoverable resources from Venezuela's heavy oil in the Orinoco Oil Belt at 513 billion barrels. The USGS did not attempt to provide an estimate of how much of this quantity would be economically recoverable; that portion will vary depending on the global price of oil.[2][3]

Venezuela's tar sands oil, also known as heavy oil, is in a position to play a major role in the global market because of the fact that it complements the light sweet that dominates the new production unleashed by the US shale oil boom. Since the US's own refineries are more suited to heavy oil, the US is expected to direct its production toward Europe, where refineries are better suited to light sweet crude. This opens up the demand by the US for either Venezuelan or Canadian hevay oil.

CO2 Emissions

The development of the tar sands would dramatically increase global GHG emissions, with estimates of up to 84 MT CO2e per year.[4] [5] Another estimate is 1.84 million barrels per day of surface extraction, and 2.96 million barrels per day of in situ extraction by 2040. Applied to a 40-year period, that amounts to 70 billion barrels, or 30.10 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, based on .43 metric tonnes of CO2 per barrel of oil or natural gas liquids, and 0.0550 metric tonnes of CO2 per thousand cubic feet of natural gas.[6] Full extraction of the recoverable reserves would result in the release of 221 billion tonnes of CO2, based on the US EIA median estimate of 513 billion barrels of recoverable oil (see above) and the US EPA conversion factor of .43 metric tonnes of CO2 per barrel of oil.[7]

International Pressure on Venezuela

Since nationalization of its oil industry, Venezuela has come under growing international pressure. In November 2017, the European Union prohibited arms sales, set up a system for freezing assets and announced new travel restrictions on some government officials. In February 2018, the United States banned exports of heavy naphtha to Venezuela, a key diluent needed in oil production.[8]

Companies Involved

After nationalization of the Orinoco Belt in 2007, all projects are majority-controlled by Venezuela's national oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA).[9]

After the decree, ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, and PetroCanada abandoned their involvement in the country and initiated lawsuits to recover the value of the assets they had lost. Other companies, including Chevron, Total, Statoil, and BP chose to remain in the country.[10][11] From 2007 to 2016, Venezuela also received $56 billion in cash injections from China, which took oil payments in lieu of cash.[12]

BP's main license is for the Petromonagas block, which currently produces around 110,000 barrels of oil per day, and may contain up to 1.2 billion barrels in total. BP controls 16.66% of the project, with the rest being held by PDVSA. BP is also developing proposals for commercial production of the Ayacucho 2 block, as part of the conglomerate TNK-BP92.[13]

In 2017, Venezuela selected the little known Dutch company Stichting Administratiekantoor Inversiones Petroleras Iberoamericanas to be its 40% partner in a new joint venture at the Junin 10 oil block in the Orinoco Belt region. The new joint venture will be called Petrosur.[14]

In January 2010, Italian oil company Eni and PDVSA signed an agreement to develop the Junin 5 block, with Eni holding a 40% stake in the joint venture. This block is one of the most lucrative, with an estimated 35 billion barrels of oil. The plan is to produce 75,000 barrels per day by 2013, with a long-term goal of 240,000 barrels per day, and to construct a new refinery for upgrading as much as 350,000 barrels of tar sands oil per day. Eni is investing $300 million for the project initially, rising to $646 million as the development achieves certain milestones. It is worth noting that the Venezuelan government compensated Eni with a $700 million payment for the nationalisation of the Dacion oil field in 2006.[13]

As of mid 2018, Spanish company Repsol continues to be heavily involved in Venezuelan heavy oil, iwth an 11% share of a consortium known as Petrocarabobo that includes the Venezuela Petroleum Corporation (CVP) and other oil companies.[15]

Potential ESG Risks

Corruption issues

President Maduro has aggressively purged and arrested executives at PDVSA under the banner of weeding out corruption, and put a military general with no experience with oil in charge of the company. PDVSA has a long-held reputation for shady conduct, and Maduro’s regime has argued that the company needs to root out graft to become more efficient and deliver more revenue for the government. But analysts say that arrests also serve another purpose: consolidating power for a beleaguered president who has lost the trust of the country’s population as it endures widespread food shortages and teeters on the edge of a debt crisis. Venezuela is currently struggling to service about $120 billion worth of debt as its economy remains locked in a tailspin due to plunging global oil prices.[16]

Environmental

The Orinoco River is 2,140 km long, and the surrounding area is a wetland of high biodiversity and home to many endangered species. In 2012 Heinrich Böll Stiftung found that "while there is a legal requirement in Venezuela for all oil projects to carry out environmental impact assessments (EIA), including baseline studies, these studies do not appear to have been published and there is no information on any more recent EIAs carried out by PDVSA in relation to operations in the Orinoco Belt."[17]

NGO's Involved

Local Opposition

Local opposition is minimal due to the country's dire economic situation.

Status of Project

Venezuela's Orinoco Belt occupies a much smaller footprint than tar sand basins in Canada and is easier to extract and export because it is warmer, closer to the surface, has more uniform viscosity, and can be more easily transported. Production was 600,000 bpd in 2015 with a goal of 2.1 million bpd by 2019.[18] Overall, national oil production had dropped from 2.3 million barrels per day in January 2016 to 1.6 million barrels per day in January 2018; specific figures for production in recent years for heavy oil production as a share of overall national oil production are not available.[19]

Infrastructure

The decrepitude of Venezuela's energy infrastructure is a major obstacle to increasing tar sands production and oil exports.[20] More than 80 percent of Venezuela's exports leave from one of two ports — Puerto Jose or Puerto La Cruz — located near each other on the coast of Anzoategui state. Puerto Jose handles two-thirds of the country's oil exports and also hosts an upgrading facility. Venezuela is now seeking foreign investment to upgrade this infrastructure.[21]

Domestic Political Situation

Tax Revenue

With the nationalization of its oil industry in 2007, the Venezuelan government promised to better distribute oil revenues for social programs. “We guaranteed that the country would have fair profits like other nations of the world, by increasing the royalty rate from 1 percent to 33 percent. Previously, for each 100 produced oil barrels, they [the transnational companies] would take 99 [percent] and the Venezuelan people would take 1. This figure became the lowest rate ever paid in the world for oil exploration,” said Oil Minister Rafael Ramírez. Between 2001 and 2011, the amount of oil taxes collected reached $356.76 billion, compared to $23.4 billion in the previous decade."[22]

The dire state of the country's economy has created a situation in which the government and popular opinion favor increasing economic production at any cost, with the use of revenues being a distant, secondary consideration.

Alternatives

Venezuela's Guri Dam is the largest hydroeletric power project in the world and supplies most of the country's electricity. Climate-change-induced drought has caused the dam's reservoir to fall below critical levels and is contributing to power shortages. The country's economic situation makes it unlikely to that new renewable projects can be funded or completed in the near future.[23]

Project Economics

Subsidies

Under President Chavez, the majority of a US$20 billion long-term loan agreement from the China Development Bank (CDB), half of which is renminbi-denominated, was received by PDVSA in return for crude oil or diesel. A large proportion has also gone into funding Venezuelan infrastructure projects. Resources channelled into the ‘China Fund’ – which has received around US$51 billion from CDB – were spent on big infrastructure projects, such as the addition of new lines to the Caracas Metro system. Similar projects were introduced in Maracaibo, with the construction of two new bridges over the Orinoco River and Valencia, with the development of its rail network.[24] To ramp up tar sands production, it is likely that the current government will seek to subsidize its energy infrastructure on an even greater scale.

Financing

The successful campaign to convince HSBC, RBS, and other European banks to reduce or stop financing oil sands projects might limit development of Venezuela's tar sands, but not very dramatically if the country leverages its relationships with China and other countries where such campaigns have not gotten much traction.

No comments:

Post a Comment