1). “Shocking U.S. Defeat: China's Rare Earth Checkmate Is NOT What Media Pretends”, Oct 13, 2025, Pascal Lottaz discusses the Chinese actions to limit U.S. Military Industrial Complex access to Rare Earth Minerals, Neutrality Studies, duration of video 30:14, at < https://www.youtube.com/watch?

2). “China’s New Rare Earth and Magnet Restrictions Threaten U.S. Defense Supply Chains”, Oct 9, 2025, Gracelin Baskaran, Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), at < https://www.csis.org/analysis/

3). “The Consequences of China’s New Rare Earths Export Restrictions”, Apr 14, 2025, Gracelin Baskaran & Meredith Schwartz, Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), at < https://www.csis.org/analysis/

4). “What China’s Ban on Rare Earths Processing Technology Exports Means”, Jan 8, 2024, Gracelin Baskaran, Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), at < https://www.csis.org/analysis/

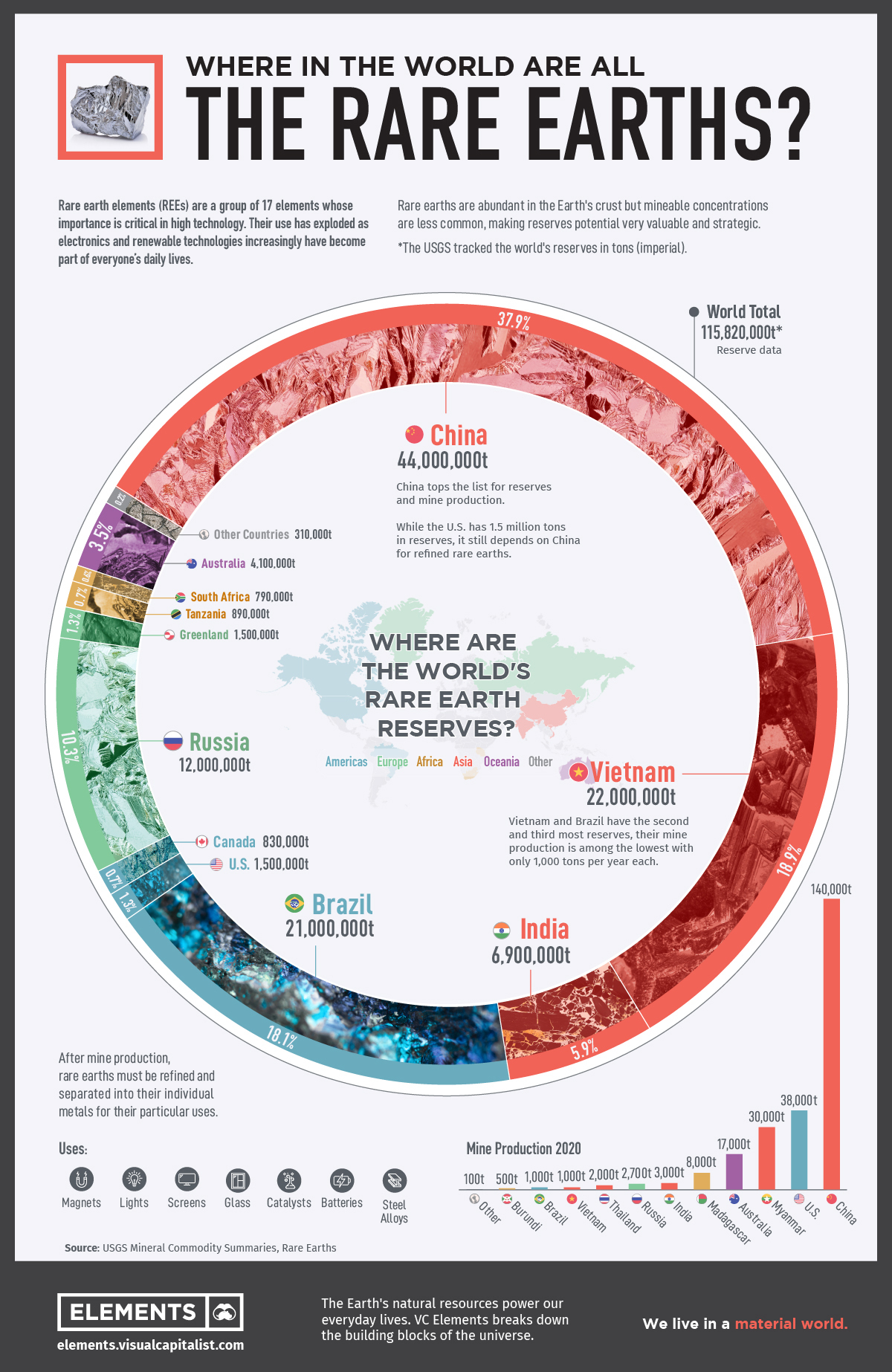

5). “Rare Earth Elements: Where in the World Are They?”, Nov 23, 2021, Nicholas LePan, Visual Capitalist, at < https://www.visualcapitalist.

6). “The REAL reason why Trump is attacking Latin America”, Oct 25, 2025, Ben Norton discusses the moves of the U.S. Ruling class, as embodied in the Donald Trump regime, Geopolitical Economy Report, duration of video 36:42, at < https://www.youtube.com/watch?

7). “Chas Freeman: Imperial Overstretch - 500 Years of Dominance Come to an End”, Oct 25, 2025, Glen Diesen interviews Chas Freeman, Glen Diesen, duration of video 45:23, at < https://glenndiesen.substack.

Introduction by desmond morista: The Trump Regime, that has in general been successful in implementing its agenda on the American people (taxing their opponents to reward their pals) is on much shakier ground in international affairs as most of the world perceives that the U.S. is much weaker than it was even just one or two years ago and certainly than was the case a few decades ago. In Item 1)., “Shocking U.S. Defeat: ….”, Pascal Lottaz points out that China has taken action to basically cut off the U.S. Military Industrial Complex (MIC) from access to the 17 Rare Earth Elements (REEs). These are materials that are absolutely essential to producing everything from cell phones, to computers, to sophisticated weapons. The U.S. military production operation reportedly has about 1.5 million pounds of REEs stockpiled, but that will last only a limited amount of time. Item 2)., “China’s New Rare Earth ….”; Item 3)., “The Consequences of ….”; and Item 4)., “What China’s Ban ….”, all address aspects of the Chinese ban on REEs for use producing weapons by the U.S. MIC. In Item 2). the discussion points out that: “The new measures mark a sharp escalation in Beijing’s long-running strategy to weaponize its dominance in rare earths. China announced a ban on rare earth extraction and separation technologies on December 21, 2023. On April 4, 2025, the Ministry of Commerce introduced export restrictions on seven rare earth elements in retaliation for President Trump’s new tariffs on Chinese goods”. (Emphasis added) In Item 3)., the author points out that each “.... F-35 fighter jet contains over 900 pounds of REEs. An Arleigh Burke-class DDG-51 destroyer requires approximately 5,200 pounds, while a Virginia-class submarine uses around 9,200 pounds.”

In Item 5)., “Rare Earth Elements: ….” provides an interesting graphic showing where most deposits of REEs are located. The location of deposits is pretty daunting for U.S. interests that want to build mines and processing plants. China is home to 37.9%, Vietnam has 18.9%, Brazil is next with 18.1%, Russia has 10.9%, and India is where 5.9% are located. In other words 91.7% of the world's REEs are located in places that are friendly with or at the least are geographically very close to China. Mines take 3 – 5 years to build and get operational and processing centers as much or more. All this gives an incentive to the U.S. ruling class to use military force now, before the balance of forces becomes too tough to “win” some sort of war. Unfortunately some analysts say that the U.S. rulers are ready to use nuclear weapons.

Item 6)., “The REAL reason ….” discusses the reasons that Trump is working on starting a war with Venezuela. A basic issue that Norton does not discuss is the point that John Mearsheimer always makes: namely that making sure there is no real state level defiance of U.S. power in the Western Hemisphere has served the U.S. ruling class well. They never have had to worry about serious problems in “their back yard”. This might be changing as China and Russia become more powerful. Already the economic realities are working against the U.S. rulers and in favor of the Chinese who increasingly dominate the trader relationships of Latin American societies. The result is that Trump is making absurd claims that short range “cigarette boats near Venezuela are taking drugs to the U.S. well about 1,300 miles away. After plenty of criticism and after several people pointed out that the drug traffickers mostly use the Pacific Coast, U.S. warplanes have now bombed more than one boat there killing several people. The U.S. regime has claimed that the Socialist President of Colombia is a drug trafficker, an absurd charge belied by the close relationships between proven drug trafficking Colombian Presidents and U.S. politicians including Trump and other presidents. Another glaring issue, not taken up by Norton, is that most cocaine now leaves from Ecuador in banana boats owned by the family of the President of Ecuador.

Finally Item 7)., “Chas Freeman: Imperial Overstretch ….” provides another erudite discussion of the reasons for the bullying and crass and hard nosed tactics used by the Americans in dealing with other countries. Freeman, who served as a high official in various posts in the U.S. government is appalled at what he sees and thinks the U.S. is coming apart.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

1). “Shocking U.S. Defeat: China's Rare Earth Checkmate Is NOT What Media Pretends”, Oct 13, 2025, Pascal Lottaz discusses the Chinese actions to limit U.S. Military Industrial Complex access to Rare Earth Minerals, Neutrality Studies, duration of video 30:14, at < https://www.youtube.com/watch?

China’s New Rare Earth and Magnet Restrictions Threaten U.S. Defense Supply Chains

In advance of President Donald Trump’s upcoming visit to South Korea later this month—where he is expected to meet Chinese President Xi Jinping for the first time since 2019—China announced that it has expanded its restrictions on rare earth and permanent magnet exports. The Chinese Ministry of Commerce’s Announcement No. 61 of 2025 implements the strictest rare earth and permanent magnet export controls to date. The move both strengthens Beijing’s leverage in upcoming talks while also undercutting U.S. efforts to bolster its industrial base.

Q1: What is new about today’s rare earth and permanent magnet export restrictions?

A1: The new export controls mark the first time China has applied the foreign direct product rule (FDPR)—a mechanism introduced in 1959 and long used by Washington to restrict semiconductor exports to China. The FDPR enables the United States to regulate the sale of foreign-made products if they incorporate U.S. technology, software, or equipment, even when produced by non-U.S. companies abroad. In effect, if U.S. technology appears anywhere in the supply chain, Washington can assert jurisdiction.

Under the measures announced today, foreign firms will now be required to obtain Chinese government approval to export magnets that contain even trace amounts of Chinese-origin rare earth materials—or that were produced using Chinese mining, processing, or magnet-making technologies. The new licensing framework will apply to foreign-produced rare earth magnets and select semiconductor materials that contain at least 0.1 percent heavy rare earth elements sourced from China.

Given China’s dominance in the sector—accounting for roughly 70 percent of rare earth mining, 90 percent of separation and processing, and 93 percent of magnet manufacturing—these developments will have major national security implications.

Q2: What do the new restrictions mean for the defense and semiconductor industries?

A2: Rare earths are crucial for various defense technologies, including F-35 fighter jets, Virginia- and Columbia-class submarines, Tomahawk missiles, radar systems, Predator unmanned aerial vehicles, and the Joint Direct Attack Munition series of smart bombs. The United States is already struggling to keep pace in the production of these systems. Meanwhile, China is rapidly scaling up its munitions manufacturing capacity and acquiring advanced weapons platforms and equipment at a rate estimated to be five to six times faster than that of the United States.

The newly announced restrictions represent China’s most consequential measures to date targeting the defense sector. Under the new rules, starting December 1, 2025, companies with any affiliation to foreign militaries—including those of the United States—will be largely denied export licenses. The Ministry of Commerce also made clear that any requests to use rare earths for military purposes will be automatically rejected. In effect, the policy seeks to prevent direct or indirect contributions of Chinese-origin rare earths or related technologies to foreign defense supply chains.

Even before these latest measures, the U.S. defense industrial base faced significant challenges and had limited production capacity and limited ability to rapidly scale to meet rising defense technology needs. The new restrictions will only deepen these vulnerabilities, further widening the capability gap and allowing China to accelerate the expansion of its military strength at a faster pace than the United States at a time when tension is rising in the Indo-Pacific region.

Additionally, export license applications for rare earth materials used in highly advanced technologies, including sub-14-nanometer semiconductors, next-generation memory chips, semiconductor manufacturing or testing equipment, will now be subject to case-by-case review by Chinese authorities. Companies will likely need to provide detailed documentation on end users, technical specifications, and intended applications before any export is authorized. The individualized review process gives Chinese authorities significant discretion to delay, deny, or condition exports, effectively introducing a new layer of strategic control over the global supply of rare earth inputs critical to advanced computing and defense technologies.

Q3: How is China tightening control over the outflow of its skills and technologies?

A3: Under the new measures, Chinese nationals are barred from engaging in or providing support for overseas projects involving rare earth exploration, extraction, processing, or magnet manufacturing unless they first obtain explicit authorization from Chinese authorities. By tightening control over the movement of expertise, China aims to prevent the outflow of proprietary technologies and know-how that have made it the global leader in rare earth mining and magnet production. These restrictions build on the rare earth processing technology export ban in December 2023.

Q4: Why are the new export restrictions likely a negotiation tactic?

A4: In its announcement, the Ministry of Commerce stated that China remains open to enhancing communication and cooperation with other countries through both multilateral and bilateral export control dialogues. The ministry emphasized that such dialogue seeks to promote compliant trade while protecting the security and stability of global industrial and supply chains.

Q5: How do these restrictions build on China’s earlier rare earth export controls?

A5: The new measures mark a sharp escalation in Beijing’s long-running strategy to weaponize its dominance in rare earths. China announced a ban on rare earth extraction and separation technologies on December 21, 2023. On April 4, 2025, the Ministry of Commerce introduced export restrictions on seven rare earth elements in retaliation for President Trump’s new tariffs on Chinese goods.

Subsequent diplomacy offered only a temporary reprieve. During the May 11 talks in Switzerland, U.S. and Chinese officials agreed to a 90-day tariff truce, which included removing U.S. companies from China’s trade blacklist and restoring their access to rare earth supplies. Yet stability proved short-lived: U.S. manufacturers soon began shutting down production amid ongoing shortages, as China delayed the issuance of export licenses despite not formally abandoning the deal. Tensions flared again when President Trump accused Beijing of backtracking on its commitments. Ultimately, on June 11, 2025, following two days of negotiations in London attended by U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, both sides reached a new trade framework—but the episode underscored how Beijing’s rare earth policy has evolved into a potent instrument of economic and geopolitical leverage.

Q6: What is the United States doing to build its rare earth and permanent magnet capabilities to reduce China’s leverage?

A6: Noveon Magnetics is currently the only manufacturer of rare earth magnets in the United States. This week, Noveon Magnetics and Lynas Rare Earths announced a memorandum of understanding to establish a strategic partnership focused on building a scalable, domestic supply chain for rare earth permanent magnets in the United States.

In July 2025, as part of a landmark agreement, the Department of Defense (recently renamed the Department of War) invested $400 million in equity into MP Materials, making the U.S. government the company’s largest shareholder. The deal also includes a 10-year price floor commitment of $110 per kilogram for MP Materials’ NdPr (neodymium-praseodymium) products, designed to protect the commercial viability of the company amidst low prices stemming from Chinese overproduction. Additionally, the Department of War’s Office of Strategic Capital (OSC) has extended a $150 million loan to expand MP Materials’ Mountain Pass, California, facility, adding heavy rare earth separation capabilities to strengthen domestic processing capacity. MP Materials has also announced plans to build its second U.S. magnet manufacturing facility, known as the “10X Facility.” The Department of War has entered into a 10-year offtake agreement for 100 percent of the facility’s magnet output. It will take time to ramp up these capabilities. Until then, China retains a significant amount of leverage over supply chains crucial for national and economic security.

Gracelin Baskaran is director of the Critical Minerals Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

The Consequences of China’s New Rare Earths Export Restrictions

On April 4, China’s Ministry of Commerce imposed export restrictions on seven rare earth elements (REEs) and magnets used in the defense, energy, and automotive sectors in response to U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariff increases on Chinese products. The new restrictions apply to 7 of 17 REEs—samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium—and requires companies to secure special export licenses to export the minerals and magnets.

Q1: To what extent will the most recent export restrictions on rare earths impact U.S. sourcing of these critical minerals for defense technologies?

A1: There are various types of export restrictions: non-automatic licensing, tariffs, quotas, and an outright ban. The new restrictions are not a ban; rather, they require firms to apply for a license to export rare earths. This development has three implications: first, there will likely be a pause in exports as the Chinese government establishes this licensing system. Second, there is also likely to be disruptions in supply to some U.S. firms given that the announcement also placed 16 U.S. entities on its export control list, limiting them from receiving dual-use goods. All but one of the firms on the list are in the defense and aerospace industries. It is unclear how China will implement the new licensing system. And third, the licensing system may be dynamic and could incentivize countries across the world to cooperate with China to prevent disruptions in their rare earths supply.

Q2: What is the significance of the focus on heavy rare earths given U.S. supply chain vulnerabilities?

A2: The restrictions apply to seven medium and heavy rare earths: samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium. The United States is particularly vulnerable for these supply chains. Until 2023, China accounted for 99 percent of global heavy REEs processing, with only minimal output from a refinery in Vietnam. However, that facility has been shut down for the past year due to a tax dispute, effectively giving China a monopoly over supply. China did not impose restrictions on light rare earths, for which a more diverse set of countries undertake processing.

Q3: Why are rare earths significant to U.S. national security?

A3: REEs are crucial for a range of defense technologies, including F-35 fighter jets, Virginia- and Columbia-class submarines, Tomahawk missiles, radar systems, Predator unmanned aerial vehicles, and the Joint Direct Attack Munition series of smart bombs. For example, the F-35 fighter jet contains over 900 pounds of REEs. An Arleigh Burke-class DDG-51 destroyer requires approximately 5,200 pounds, while a Virginia-class submarine uses around 9,200 pounds.

The United States is already on the back foot when it comes to manufacturing these defense technologies. China is rapidly expanding its munitions production and acquiring advanced weapons systems and equipment at a pace five to six times faster than the United States. While China is preparing with a wartime mindset, the United States continues to operate under peacetime conditions. Even before the latest restrictions, the U.S. defense industrial base struggled with limited capacity and lacked the ability to scale up production to meet defense technology demands. Further bans on critical minerals inputs will only widen the gap, enabling China to strengthen its military capabilities more quickly than the United States.

Q4: Is the U.S. rare earths industry ready to fill the gap in the event of a shortfall?

A4: No. There is no heavy rare earths separation happening in the United States at present. The development of these capabilities is currently underway. In its 2024 National Defense Industrial Strategy, the Department of Defense (DOD) set a goal to develop a complete mine-to-magnet REE supply chain that can meet all U.S. defense needs by 2027. Since 2020, the DOD has committed over $439 million toward building domestic supply chains. In 2020, the Pentagon awarded MP Materials $9.6 million through the DPA Title III program for a light rare earths separation facility at Mountain Pass, California. In 2022, the Pentagon awarded an additional $35 million for a heavy rare earths processing facility. These facilities would be the first of their kind in the United States, fully integrating the rare earths supply chain from mining, separating, and leaching in Mountain Pass to refining and magnet production in Fort Worth, Texas. But even when these facilities are fully operational, MP Materials will only be producing 1,000 tons of neodymium-boron-iron (NdFeB) magnets by the end of 2025—less than 1 percent of the 138,000 tons of NdFeB magnets China produced in 2018. In 2024, MP Materials announced record production of 1,300 tons of neodymium-praseodymium (NdPr) oxide. In the same year, China produced an estimated 300,000 tons of NdFeB magnets.

The DOD has thrown its support behind Lynas Rare Earth’s U.S. subsidiary, Lynas USA, as well. The company was awarded a $30.4 million DPA Title III grant in 2021 for a U.S. separation facility for light REEs and another $120 million in 2022 for a heavy REE processing facility. These DPA investments are an important step in building completely independent supply chains for REE magnets.

Even with recent investments, the United States is a long way off from meeting the DOD’s goal for a mine-to-magnet REE supply chain independent of China, and it is even further from rivaling foreign adversaries in this strategic industry. U.S. capabilities are largely early-stage. For example, in January 2025, USA Rare Earths produced its first sample of dysprosium oxide purified to 99.1 percent. Produced using ore from the Round Top deposit in Texas and processed at a research facility in Wheat Ridge Colorado, the company has called the development a breakthrough for the domestic rare earths industry. However, significant work remains to turn production of samples in a laboratory into full scale commercial production capable of reducing reliance on China. Developing mining and processing capabilities requires a long-term effort, meaning the United States will be on the back foot for the foreseeable future.

Q5: Could the United States have seen this coming?

A5: Yes. A number of policies have foreshadowed that REE export restrictions were on the horizon. China first weaponized rare earths in 2010 when it banned exports to Japan over a fishing trawler dispute. Between 2023 and 2025, China began imposing export restrictions of strategic materials to the United States, including gallium, germanium, antimony, graphite, and tungsten.

In 2023, the Select Committee on the Strategic Competition between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party published a report titled Reset, Prevent, Build: A Strategy to Win America's Economic Competition with the Chinese Communist Party. It recommended that “Congress should incentivize the production of rare earth element magnets, which are the principal end-use for rare earth elements and used in electric vehicles, wind turbines, wireless technology, and countless other products.” Specifically, it advocated for Congress to establish tax incentives to promote U.S. manufacturing.

In December 2023, China imposed a ban of REE extraction and separation technologies. It had a notable impact on developing REE supply chain capabilities outside of China due to two main factors. First, China possesses specialized technical expertise in this field that other countries do not. For instance, it has an absolute advantage in solvent extraction processing techniques for rare earths, an area where Western companies have faced challenges both in implementing advanced technological operations and in addressing environmental concerns. Second, while multiple facilities for separation, processing, and manufacturing are currently being built, completing construction and bringing them fully online will take several years.

Q6: Are there any international partners from which the United States could alternatively source heavy rare earths and fill the supply gap?

A6: While several countries are working to develop their light and heavy rare earths deposits, China maintains a monopoly on refined heavy rare earths for the time being. Australia, Brazil, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Japan, and Vietnam all have initiatives and investments underway to bolster key REE mining, processing, and research and development (R&D) as well as magnet manufacturing. For the United States to build alternative sourcing partners for long-term supply chain security, it is important to continue to provide financial and diplomatic support to ensure the success of these initiatives.

Australia is working to develop its Browns Range to become the first significant dysprosium producer outside of China. The deposit has estimated dysprosium reserves of 2,294 tons, to be unlocked in a multistage process resulting in 279,000 kg of dysprosium per year. However, much work remains to be done to build processing and refining capacity outside of China. Australia’s Lynas Rare Earths is the largest producer of separated rare earths outside of China, but still sends oxides to China for refining. Australia is expected to be reliant on China for REE refining until at least 2026.

Working with international partners can also help to overcome gaps in technological know-how when it comes to REE separation and processing. A few countries lead the way in developing critical minerals and REE-specific R&D initiatives to support the development of the strategic sector. The Australian Critical Minerals Research and Development Hub is working to boost international R&D cooperation on critical minerals. The hub includes rare earth and downstream processing initiatives lead by government agencies working in partnership with industry and universities to boost technical capacity. Japan has the Center for Rare Earths Research within its Muroran Institute of Technology as well as a joint initiative with Vietnam to improve REE extraction and processing at the Rare Earth Research and Technology Transfer Centre in Hanoi. The initiative was launched in 2012 as Japan looked to strengthen and diversify its REE supply chains in response to China’s REE export ban in 2010.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Rare Earth Elements: Where in the World Are They?

This was originally posted on Elements. Sign up to the free mailing list to get beautiful visualizations on natural resource megatrends in your email every week.

Rare earth elements are a group of metals that are critical ingredients for a greener economy, and the location of the reserves for mining are increasingly important and valuable.

This infographic features data from the United States Geological Society (USGS) which reveals the countries with the largest known reserves of rare earth elements (REEs).

What are Rare Earth Metals?

REEs, also called rare earth metals or rare earth oxides, or lanthanides, are a set of 17 silvery-white soft heavy metals.

The 17 rare earth elements are: lanthanum (La), cerium (Ce), praseodymium (Pr), neodymium (Nd), promethium (Pm), samarium (Sm), europium (Eu), gadolinium (Gd), terbium (Tb), dysprosium (Dy), holmium (Ho), erbium (Er), thulium (Tm), ytterbium (Yb), lutetium (Lu), scandium (Sc), and yttrium (Y).

Scandium and yttrium are not part of the lanthanide family, but end users include them because they occur in the same mineral deposits as the lanthanides and have similar chemical properties.

The term “rare earth” is a misnomer as rare earth metals are actually abundant in the Earth’s crust. However, they are rarely found in large, concentrated deposits on their own, but rather among other elements instead.

Rare Earth Elements, How Do They Work?

Most rare earth elements find their uses as catalysts and magnets in traditional and low-carbon technologies. Other important uses of rare earth elements are in the production of special metal alloys, glass, and high-performance electronics.

Alloys of neodymium (Nd) and samarium (Sm) can be used to create strong magnets that withstand high temperatures, making them ideal for a wide variety of mission critical electronics and defense applications.

| End-use | % of 2019 Rare Earth Demand |

|---|---|

| Permanent Magnets | 38% |

| Catalysts | 23% |

| Glass Polishing Powder and Additives | 13% |

| Metallurgy and Alloys | 8% |

| Battery Alloys | 9% |

| Ceramics, Pigments and Glazes | 5% |

| Phosphors | 3% |

| Other | 4% |

The strongest known magnet is an alloy of neodymium with iron and boron. Adding other REEs such as dysprosium and praseodymium can change the performance and properties of magnets.

Hybrid and electric vehicle engines, generators in wind turbines, hard disks, portable electronics and cell phones require these magnets and elements. This role in technology makes their mining and refinement a point of concern for many nations.

For example, one megawatt of wind energy capacity requires 171 kg of rare earths, a single U.S. F-35 fighter jet requires about 427 kg of rare earths, and a Virginia-class nuclear submarine uses nearly 4.2 tonnes.

Global Reserves of Rare Earth Minerals

China tops the list for mine production and reserves of rare earth elements, with 44 million tons in reserves and 140,000 tons of annual mine production.

While Vietnam and Brazil have the second and third most reserves of rare earth metals with 22 million tons in reserves and 21 million tons, respectively, their mine production is among the lowest of all the countries at only 1,000 tons per year each.

| Country | Mine Production 2020 | Reserves | % of Total Reserves |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 140,000 | 44,000,000 | 38.0% |

| Vietnam | 1,000 | 22,000,000 | 19.0% |

| Brazil | 1,000 | 21,000,000 | 18.1% |

| Russia | 2,700 | 12,000,000 | 10.4% |

| India | 3,000 | 6,900,000 | 6.0% |

| Australia | 17,000 | 4,100,000 | 3.5% |

| United States | 38,000 | 1,500,000 | 1.3% |

| Greenland | - | 1,500,000 | 1.3% |

| Tanzania | - | 890,000 | 0.8% |

| Canada | - | 830,000 | 0.7% |

| South Africa | - | 790,000 | 0.7% |

| Other Countries | 100 | 310,000 | 0.3% |

| Burma | 30,000 | N/A | N/A |

| Madagascar | 8,000 | N/A | N/A |

| Thailand | 2,000 | N/A | N/A |

| Burundi | 500 | N/A | N/A |

| World Total | 243,300 | 115,820,000 | 100% |

While the United States has 1.5 million tons in reserves, it is largely dependent on imports from China for refined rare earths.

Ensuring a Global Supply

In the rare earth industry, China’s dominance has been no accident. Years of research and industrial policy helped the nation develop a superior position in the market, and now the country has the ability to control production and the global availability of these valuable metals.

This tight control of the supply of these important metals has the world searching for their own supplies. With the start of mining operations in other countries, China’s share of global production has fallen from 92% in 2010 to 58%< in 2020. However, China has a strong foothold in the supply chain and produced 85% of the world’s refined rare earths in 2020.

China awards production quotas to only six state-run companies:

- China Minmetals Rare Earth Co

- Chinalco Rare Earth & Metals Co

- Guangdong Rising Nonferrous

- China Northern Rare Earth Group

- China Southern Rare Earth Group

- Xiamen Tungsten

As the demand for REEs increases, the world will need tap these reserves. This graphic could provide clues as to the next source of rare earth elements.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

6). “The REAL reason why Trump is attacking Latin America”, Oct 25, 2025, Ben Norton discusses the moves of the U.S. Ruling class, as embodied in the Donald Trump regime, Geopolitical Economy Report, duration of video 36:42, at < https://www.youtube.com/watch?

Ambassador Chas Freeman discusses the current historical time we live through, as the foundations for 500 years of dominance come to an end. Ambassador Freeman was a former Assistant Secretary of Defense, earning the highest public service awards of the Department of Defense for his roles in designing a NATO-centered post-Cold War European security system and in reestablishing defense and military relations with China. He served as U. S. Ambassador to Saudi Arabia (during operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm). He was Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs during the historic U.S. mediation of Namibian independence from South Africa and Cuban troop withdrawal from Angola.

TRANSCRIPT

No comments:

Post a Comment