1). “In Texas’ biggest purple county, this far-right Republican is creating a playbook for local governing: From cutting social services to changing election rules, Tarrant County Judge Tim O’Hare has pushed his agenda with an uncompromising approach”, Oct. 11, 2024, Robert Donen, The Texas Tribune, & Jeremy Schwartz, The Texas Tribune and ProPublica, The Texas Tribune, at < https://www.texastribune.org/

2). “Tarrant County GOP sought an election advantage with failed effort to shutter college voting locations: In a resolution signed Friday, the party blasted two Republicans who voted against the measure and accused them of undermining its electoral chances”, Sept. 18, 2024 Updated: Sept. 19, 2024, Juan Salinas II, The Texas Tribune, at < https://www.texastribune.org/

3). “These Are the Right-Wing Ideologues Taking Over School Boards: Conservative consultants and PACs are turning Texas school boards into partisan ``battlegrounds”, Nov. 13, 2023, Steven Monacelli, Texas Observer, at < https://www.texasobserver.org/

4). “How the ‘Southlake Playbook’ brought partisan battles to America’s school boards”, May 10, 2024, Mike Hixenbaugh, Chalkbeat, at < https://www.chalkbeat.org/

~~ recommended by dmorista ~~

Introduction by dmorista : In the midst of the big election campaign between the Duopoly Candidates, the inadequate Kamala Harris vs the Dangerous and Hideous Donald Trump (yes I clearly support leftists voting for Harris in places where there is any chance of an outcome that helps the Trumpista Forces); it is easy to ignore state and local politics and how it affects those of us who live in the Red States of the U.S.

However, the importance of control of local and state governments is key to how the Right-wing is maintaining power in various Red States, particularly those where there has been high levels of population growth and an influx of Non-Maga base populations. Texas stands out, along with Florida and Georgia, as places that have become at least Purple States, and more likely Blue States. Item 1)., “In Texas’ biggest purple county, ….”, and Item 2)., “Tarrant County GOP ….”, both address aspects of the current regime of Tarrant County Judge Tim O’Hare and how he and his minions are using extreme hard-ball tactics to dominate the fairly evenly divided Tarrant County and to impose the harsh right-wing woman hating agenda of the Texas Republican Fascist faction.

Tarrant County Judge Tim O'Hare: Harsh Minority Rule in Texas

Item 3)., “These Are the Right-Wing Ideologues …. takes look at the origins of the far-right's assault on public education and the control of local school boards as a major wedge issue to mobilize right-wingers and theocrats on the local, regional, and hopefully for them the national level.

Item 4)., “How the ‘Southlake Playbook’ brought ….”, looks at the migration of the original tactics developed at first in Southlake Independent School District, in suburban Tarrant County, Texas. Tarrant County is the most conservative major urban county in Texas and is closely divided between Republicans and Democrats. The other major Urban counties of Texas are all controlled by the Democratic Party.

This is a major part of the struggle for the future of our society, and is not as well known as it should be by many on the left or among the liberals.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

In Texas’ biggest purple county, this far-right Republican is creating a playbook for local governing

From cutting social services to changing election rules, Tarrant County Judge Tim O’Hare has pushed his agenda with an uncompromising approach.

This article is co-published with ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for ProPublica’s Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox as soon as they are published. Also, sign up for The Brief, our daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news.

Over the past two decades, Tim O’Hare methodically amassed power in North Texas as he pushed incendiary policies such as banning undocumented immigrants from renting homes and vilifying school curriculum that encouraged students to embrace diversity.

He rode a wave of conservative resentment, leaping from City Council member of Farmers Branch, a suburb north of Dallas, in 2005 to its mayor to the leader of the Tarrant County Republican Party.

Three years ago, O’Hare sought his highest political office yet, running for the top elected position in the nation’s 15th-largest county, which is home to Fort Worth. Backed by influential evangelical churches and money from powerful oil industry billionaires, O’Hare promised voters he would weed out “diversity inclusion nonsense” and accused some Democrats of hating America. His win in November 2022 gave the GOP’s far right new sway over the Tarrant County Commissioners Court, turning a government that once prided itself on bipartisanship into a new front of the culture war.

“I was not looking to do this at all, but they came after our police,” he said in his victory speech on election night. “They came after our schools. They came after our country. They came after our churches.”

In Texas and across the country, far-right candidates have won control of school boards, swiftly banning books, halting diversity efforts and altering curricula that do not align with their beliefs. O’Hare’s election in Tarrant County, however, takes the battle from the schoolhouse to county government, offering a rare look at what happens when hard-liners win the majority and exert their influence over municipal affairs in a closely divided county.

Since he was elected county judge — a position similar to that of mayor in a city — O’Hare has pushed his agenda with an uncompromising approach. He has led efforts to cut funding to nonprofits that work with at-risk children, citing their views on racial inequality and LGBTQ+ rights. And he has pushed election law changes that local Republican leaders said would favor them.

O’Hare’s rise in Tarrant County has come as he and his allies continue to align with once-fringe figures while targeting private citizens with whom they disagree politically. In July, O’Hare had a local pastor removed from a public meeting for speaking eight seconds over his allotted time. Days later, O’Hare appeared onstage at a conference that urged attendees to resist a Democratic campaign to “rid the earth of the white race” and embrace Christian nationalism. The agenda prompted some right-wing Republicans to condemn or pull out of the event.

“We’re seeing a shift of what conservatism looks like, and at the lower levels, they’re testing how extreme it can get,” said Robert Futrell, a sociologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas who studies political extremism. “The goal is to capture local Republican Party infrastructure and positions and own the party, turning it to more extremist goals.”

sent weekday mornings.

Frequently, those aims include pushing back against broader LGBTQ+ acceptance, downplaying the nation’s history of racism and the lingering disparities caused by it, stemming immigration, and falsely claiming that America was founded as a Christian nation and that its laws and institutions should thus reflect conservative evangelical beliefs.

O’Hare declined multiple interview requests and did not answer detailed lists of questions emailed to him. His spokesperson instead touted a list of eight accomplishments, including cutting county spending and lowering local property tax rates.

With 2.2 million people, Tarrant County is Texas’ most significant remaining battleground for Democrats and Republicans. When the county voted for Beto O’Rourke for U.S. Senate in 2018 and Joe Biden for president in 2020, many political observers suspected the end was nigh for the era of Republican dominance in the purple county.

Two years later, voters elected the most hard-line Tarrant County leader in decades. After two years under O’Hare’s leadership, voters in November will decide two races between Republican allies of O’Hare and their Democratic opponents. The election of both Democrats would put O’Hare into the minority.

The changes in county leadership have been dramatic, said O’Hare’s Republican predecessor, Glen Whitley, who served as Tarrant County judge from 2007 until retiring in 2022. Whitley said O’Hare has implanted an “us vs. them” ideology that has increasingly been mainstreamed on the right.

“They no longer feel like they have to compromise,” said Whitley, who recently endorsed Democratic Vice President Kamala Harris for president and U.S. Rep. Colin Allred of Texas in the U.S. Senate race. “You either vote with these people 100% of the time, or you’re their enemy.”

Political rise

In 2005, when O’Hare initially ran unopposed for a seat on the City Council in Farmers Branch, a small town just outside of Tarrant County, his platform included plans to revitalize the public library and bring in new restaurants. In 2006, however, O’Hare began taking positions that were outside of the Republican mainstream at the time. He pushed for the diversifying town to declare English its official language, ban landlords from renting to residents without proof of citizenship, and stop publishing public materials in Spanish.

“The reason I got on the City Council was because I saw our property values declining or increasing at a level that was below the rate of inflation,” O’Hare said at the time. “When that happens, people move out of our neighborhoods, and what I would call less desirable people move into the neighborhoods, people who don’t value education, people who don’t value taking care of their properties.”

Hispanic residents mobilized and sued to block the rental ban’s implementation. O’Hare doubled down: He pushed for Farmers Branch police to partner with immigration enforcement authorities to detain and deport people in the country illegally, and urged residents to oppose a grocer’s plan to open a store that catered to Hispanics, arguing it was “reasonable” to prefer “a grocery store that appeals to higher-end consumers.”

O’Hare was elected as mayor in 2008. Foreshadowing moves he’d make as Tarrant County judge, he abruptly ended a public meeting after cutting off and removing one resident who criticized him. He led opposition to the local high school’s Gay-Straight Alliance and fought against a mentorship program for at-risk high school students that included volunteers from a Hispanic group that opposed his immigration resolution.

Tarrant County GOP sought an election advantage with failed effort to shutter college voting locations

Meanwhile, the city continued to defend the immigration ordinance after it was repeatedly struck down by federal judges. As costs for the seven-year legal battle ballooned, Farmers Branch dipped into its reserves, cut nearly two dozen city employees and outsourced services at the library that O’Hare had campaigned on improving during his City Council run. “At the end of the day, this will be money well spent, and it will be a good investment in our community’s future,” O’Hare said after the town laid off staff in 2008.

O’Hare stepped down as mayor in 2011. Three years later, after the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the city’s appeal, Farmers Branch stopped defending the ordinance. It was never enforced, but the related lawsuits cost the town $6.6 million, city officials said in 2016.

After leaving office, O’Hare moved his family a few miles away to Tarrant County, where demographic changes have dropped the share of white residents from 62% of the county’s population in 2000 to 43% in 2020.

Home to some of the nation’s most influential evangelical churches and four of former President Donald Trump’s spiritual advisers, the county is an epicenter for ultraconservative movements in Texas, including those that call for Christians to exert dominance over all aspects of society. In 2016, O’Hare was elected chair of the Tarrant County GOP. Under him, the party distributed mailers that listed the primary voting records for local candidates — breaking with the longstanding nonpartisan tradition of county elections.

In 2020, following a series of racist incidents at the mostly white Carroll High School in Southlake — including one viral clip in which white students chanted the N-word — O’Hare co-founded a political action committee that raised hundreds of thousands of dollars to oust school board members who supported the Carroll Independent School District’s plans for diversity and inclusion programming. The dispute helped catapult the small Tarrant County suburb into the national spotlight amid Republican panic over critical race theory and “gender ideology,” and created a blueprint for right-wing organizing that was copied in suburbs across America.

In 2021, O’Hare launched his campaign for Tarrant County judge, squaring off in the GOP primary against the more moderate five-term mayor of Fort Worth, whom he painted as a RINO, or “Republican in name only.” O’Hare rode a wave fueled by backlash to COVID-19 mandates, baseless election fraud conspiracy theories and opposition to what he called “diversity inclusion nonsense,” according to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. O’Hare’s campaign was condemned by moderate Republicans, including Whitley, the outgoing judge, who accused him of trying to “divide and pit one group against another.” O’Hare won the primary by 23 percentage points.

Whitley and other longtime Republican leaders declined to endorse O’Hare in the 2022 general election. It didn’t matter; by then, he was backed by a coalition of far-right megadonors, pastors and churches. His top campaign donors included a PAC funded by Tim Dunn and Farris Wilks. The two west Texas oil billionaires have given tens of millions of dollars to candidates and groups that oppose LGBTQ+ rights, support programs that would use public dollars to pay for private schools, and have led efforts to push moderates out of the Texas GOP.

O’Hare received another $203,000 from the We Can Keep It PAC. The PAC’s treasurer is an elder at Mercy Culture Church in Fort Worth, whose leaders have endorsed multiple GOP candidates, including O’Hare. The church’s pastor has claimed Democrats can’t be Christian and dared critics to complain to the IRS that the church was flouting federal prohibitions on political activity by nonprofits.

Transforming elections

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/8037c470262a4deecd0061740137eb92/0418%20Tarrrant%20Co%20CommCo%20ST%2009.JPG)

O’Hare took office in early 2023, as Republicans continued to question President Joe Biden’s razor-thin win in Tarrant County two years earlier. A 2022 audit by Texas’ Republican secretary of state found no evidence of widespread fraud and that Tarrant County held “a quality, transparent election.”

Despite that — and while saying he had no proof of malfeasance — O’Hare immediately set out to prevent cheating he claimed was responsible for Democrats’ steady rise in the long-purpling county. Soon after taking office, he helped launch an “election integrity unit” that he’d lead with the county sheriff who had spoken at a “Stop the Steal” rally in the days after the 2020 presidential election.

No Democrats were initially on the unit. Nor was the county’s elections administrator, Heider Garcia, who by then had faced three years of harassment, death threats and accusations of being a secret agent for Venezuela’s socialist government by election fraud conspiracy theorists. Garcia opted for radical transparency — making himself accessible to answer questions about the election process and earning praise from across the political aisle for his patient public service.

But Garcia lasted only a few months under O’Hare: In April 2023, he resigned his position, citing his relationship with O’Hare in his resignation letter. “Judge O’Hare, my formula to ‘administer a quality transparent election’ stands on respect and zero politics; compromising on these values is not an option for me,” Garcia wrote. “You made it clear in our last meeting that your formula is different, thus, my decision is to leave.”

Garcia, now the Dallas County elections administrator, did not respond to an interview request.

One day after Garcia resigned, O’Hare told members of True Texas Project — a group whose leaders have sympathized with a white nationalist mass shooter and endorsed Christian nationalism — that he was encouraged by the potential for low turnout in that year’s upcoming elections, which he said would help Republicans win more local seats. (O’Hare previously served on True Texas Project’s advisory team, according to a 2021 social media post by the group’s CEO, Julie McCarty).

In June 2024, the election integrity unit reported that, over the previous 15 months, it received 82 complaints of voter fraud — or about 0.009% of all votes cast in the 2020 presidential election in Tarrant County — and that none had resulted in criminal charges. Meanwhile, O’Hare has proposed a number of changes to the election system that Tarrant County GOP leaders have said were intended to help Republicans or hurt Democrats.

In February, O’Hare and fellow Republicans cut $10,000 in county funding to provide free bus rides to low-income residents, a program that Tarrant GOP leaders decried as a scheme to “bus Democrats to the polls.”

O'Hare said he opposed the funding on fiscal grounds. “I don’t believe it’s the county government’s responsibility to try to get more people out to the polls,” he said before the vote.

A few months later, commissioners prohibited outside organizations from registering voters inside county buildings after Tarrant County GOP leaders raised concerns about left-leaning organizations holding registration drives. Democrats and voting rights groups assailed the moves as attempts to lower voter turnout.

In September, O’Hare proposed eliminating voting locations on some college campuses that he called a “waste of money and manpower.” But this time, his Republican allies on the Commissioners Court said they could not go along with the vote and joined Democrats to defeat the measure. Tarrant County Republican leaders condemned the recalcitrant commissioners in a public resolution that made it clear they saw the effort to close polls on college campuses as a move that would help them in November. The GOP commissioners, the resolution claimed, “voted with Democrats on a key election vote that undermines the ability of Republicans to win the general election in Tarrant County.”

Manny Ramirez, one of those Republican commissioners, said in an interview he thinks the GOP should try to win college students with their conservative ideas rather than limit on-campus voting.

“We’ve been providing those same exact sites for nearly two decades,” Ramirez said. His role as commissioner, he added, is to provide “equal access to all of our citizens.”

Targeting youth programs

Less than a year into his term, O’Hare began targeting long-established nonprofits whose websites and social media accounts contained language the county judge considered politically objectionable on issues of gender and race.

In October 2023, he moved to block a $115,000 state grant to Girls Inc. of Tarrant County, for its Girl Power program offering summer camps and mentoring to help participants focus on stress management, hygiene and self-esteem.

About 90% of the youth served by Girls Inc. of Tarrant County are people of color and come from families making less than $30,000 a year, according to the organization’s website.

Four months earlier, the national Girls Inc. group, which has chapters across the country, had tweeted out its support for abortion rights and LGBTQ+ pride, which conservative media and activists seized upon.

“Girls Inc. is an extremist political indoctrination machine advocating for divisive liberal politics,” Leigh Wambsganss, the chief communications officer of Patriot Mobile, told commissioners. Patriot Mobile is a Christian nationalist cellphone company whose PAC has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars in support of far-right candidates across Tarrant County, including O’Hare.

Local leaders of Girls Inc., who did not respond to requests for comment, said at the time their chapter is independent of the national organization. They told commissioners they were reviewing their affiliation with the parent organization.

In denying the funds, O’Hare told the Commissioners Court the government shouldn’t support “an organization that is so deeply ideological and encourages the children that they are teaching to go advocate for social change.”

Commissioners killed the contract on a 3-2 party-line vote.

Six months later, O’Hare raised questions about another local nonprofit, Big Thought. It provides youth in the Tarrant County juvenile detention system with summer and after-school programs aimed at helping them get their lives back on track through music, acting and performance arts. Big Thought has had a contract with the county for the past three years and says on its website that youth who go through its programs reoffend at a lower rate than those who don’t, potentially saving taxpayers hundreds of thousands of dollars in juvenile detention costs.

At an April meeting of the Tarrant County Juvenile Board, O’Hare raised questions about the program’s advocacy for “racial equity” after reading the organization’s website, according to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. (The board’s meetings are not streamed or recorded).

Asked about O’Hare’s concerns, a Big Thought spokesperson said in an email that the organization focuses on the realities facing at-risk youth in Tarrant County. “Young people in our communities experience challenges like economic inequality, racism, and more, and it is our responsibility to provide a safe place to build the skills they need so they can thrive,” said Evan Cleveland, Big Thought’s senior director of programs.

The county’s juvenile probation director, Bennie Medlin, who has not responded to requests for comment, told board members the program had not had any “negative results” during the partnership, according to minutes of the meeting. Members of the board were not swayed and voted not to renew the program.

Three months later, at the juvenile board’s July meeting, O’Hare and a district judge proposed ending a contract with the Pennsylvania nonprofit Youth Advocate Programs after probing the nonprofit about the position it had taken in briefs to the Supreme Court, its opinion on school choice and police in schools, and whether “they work to eliminate systemic racism,” according to minutes of the meeting.

Board members voted to cut ties with the nonprofit, which had worked with the county for over three decades to provide mentoring, job training and substance abuse counseling as alternatives to detention.

Gary Ivory, the organization’s president, said that a week after the July vote, he met with O’Hare for about a half-hour in O’Hare’s office. He said O’Hare questioned him about his personal views on the LGBTQ+ community and “hot-button cultural war issues." Also during that meeting, O’Hare pulled up Youth Advocate Programs’ website, Ivory said, and asked him why the group takes funding from Everytown for Gun Safety, a nonprofit that advocates for gun control.

“They are saying if anybody is too woke in Tarrant County, we are going to put them in the dustbin of history and they won’t exist anymore,” Ivory said.

On Oct. 1, Tarrant County commissioners voted to sign a similar contract with another nonprofit. At the meeting, O’Hare denied pushing to kill Youth Advocate Programs’ contract “because of a phrase on a website.” Instead, he claimed Ivory told the juvenile board that 15% of the money Tarrant County gives the program goes to lobbyists and to “law firms to file amicus briefs against many of the things the people in that room that voted disagree with.”

Ivory said that is incorrect. “I said generally 85 cents on a dollar stays in Tarrant County and 15 cents goes to overhead,” he said. “And I made it clear that YAP doesn’t spend any of that 15 cents on the dollar for lobbying.”

Phil Sawyer, a longtime juvenile probation officer in Tarrant County who retired two years ago, said the program was well respected within the department and helped give badly needed services that the department could not provide. “It’s a shocker,” he said of the county’s decision to cut ties with the group. “Without them, it would just be insanity. There are things we can do as probation officers, but it’s not the same.”

Stifling dissent

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/9a24b3fe2637c9328702b66d61ffe212/0418%20Tarrrant%20Co%20CommCo%20ST%2014.JPG)

In recent months, O’Hare has taken aim at private citizens who disagree with him, ordering several political opponents removed from Commissioners Court meetings and calling for the firing of a local college professor.

As Ryon Price’s allotted three minutes of public comment during the July 2 Commissioners Court meeting expired, O’Hare issued a sharp warning to the man, a local Baptist minister who was a frequent antagonist of O’Hare’s at such meetings: “Your time is up.”

It’s not uncommon for residents to go over their allotted time during public comment sessions. But after Price continued criticizing conditions in the Tarrant County Jail for an extra eight seconds, O’Hare ordered sheriff’s deputies to step in: “He’s now held in contempt. Remove him.”

As Price was escorted out of the meeting, someone in the audience booed. “Was that you?” O’Hare snapped. “Well, try me.”

Price said that in the lobby, sheriff’s deputies handed him a trespassing warning that banned him from the premises. “I think it’s symbolic of a broader, more authoritarian shift” in Tarrant County government, Price said of his removal. “And I have to wonder if he really wants to govern this place, a place that splits red and blue evenly, or just please some higher-ups in his own party.”

Price appealed his ban to the Tarrant County sheriff’s department and said the appeal was granted in August, allowing him to resume addressing the court during public comment sessions.

Minutes after Price was escorted from that July meeting, Lon Burnam, a Democrat who served nine terms in the Texas House, approached O’Hare to confront him about his decision to cut off another commissioner who was requesting information about sheriff department policies. Burnam later received a trespass warning from sheriff’s deputies and said he is banned from public meetings until Jan. 1.

At their meeting two weeks later, commissioners amended public speaking rules as O’Hare warned residents that “refusal to abide by the Commissioners Court’s order or my order as the presiding judge or continued disruption of the meeting may result in arrest and prosecution under the laws of the state of Texas.”

O’Hare said the changes were needed to ensure civility in the meeting room. “This is not in any way shape or form attempting to stifle free speech,” he said during the meeting.

Also in August, O’Hare called for the firing of a Texas Christian University professor over social media posts from 2021 that called for police to be abolished. The professor, Alexandra Edwards, drew the ire of local right-wing activists after writing about them and the pro-Christian nationalism conference that O’Hare attended in July. Not long after, a local right-wing website published an article about her “antifa” views in which O’Hare called her a “radical” and said Edwards should be fired.

“The full force of the repression of the Tarrant County GOP and the various right-wing extremists kind of came down upon me,” Edwards said in an interview, adding that she was inundated with threats and harassment.

Such crackdowns are a sign that the local GOP has been taken over by extremists, said Whitley, the county’s Republican former judge.

“They’ve gone so far to the right that most folks who used to be adamant Republicans are not so much anymore,” he said, adding that some in the GOP are too afraid of retaliation by O’Hare to speak out publicly.

O’Hare’s term doesn’t end until 2027. But this year’s elections will decide which party controls the powerful commissioners court and, in some ways, will be a referendum on the first two years of his tenure in county government.

Whitley said he hopes it will be a unifying moment for voters from across the political spectrum. “I want us to be Americans, to be Texans and to not just care about parties,” he said. “I hope people will vote for the best person and not just vote for the party.”

Disclosure: Everytown for Gun Safety and Texas Christian University have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Tarrant County GOP sought an election advantage with failed effort to shutter college voting locations

In a resolution signed Friday, the party blasted two Republicans who voted against the measure and accused them of undermining its electoral chances.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/97af2a225e80efbfa325cc2a6a581918/0506%20Heider%20Tarrant%20County%20AS%2025.jpeg)

Sign up for The Brief, The Texas Tribune’s daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news.

Earlier this month, Tarrant County Judge Tim O’Hare proposed eliminating voting locations at some colleges because of their low turnout and to save costs.

Critics pointed to the thousands of students who used the locations in the past — many of whom favored liberal-leaning candidates — and accused O’Hare of wanting to suppress votes for his party’s benefit. O’Hare denied it and said college campuses were uninviting to older voters and had limited parking. Students could just go to another nearby location, he said.

But in a recent rebuke condemning Republicans who helped block O’Hare’s measure, the county’s party leaders don’t mention O’Hare’s previous arguments. Instead, in an apparent validation of critics’ concerns, the local party unanimously signed a resolution noting officials believed O’Hare’s proposal would’ve helped improve Republicans’ odds in the upcoming elections.

“Tarrant County Commissioners Manny Ramirez and Gary Fickes, Republicans elected with the support of the Republican brand and the Republican base, voted with Democrats on a key election vote that undermines the ability of Republicans to win the general election in Tarrant County,” the resolution reads.

The resolution states that Tarrant County Republican voters expect their officials to “work to advance policies that support free and fair election, that do not favor one party over other.” But it also laments that Ramirez and Fickes’ decision to keep the college voting locations jeopardizes “the party's ability to maintain robust, conservative leadership in local government.”

Voting rights advocates and Texas Democrats said the resolution amounted to a blatant admission of favoring party gains over a fair electoral process. They say it’s the same with other statewide efforts from top Republican leaders, who are trying to block other counties’ voter registration initiatives and spreading unproven claims of illegal voting. Travis County is suing top Texas officials, accusing them of violating the National Voter Registration Act.

“Tarrant County Republicans are saying the quiet part out loud,” state Rep. Chris Turner, a Democrat from Grand Prairie, told The Texas Tribune. The proposal to eliminate the college voting locations “was only about making it more difficult for young people and people of color to vote,” he said.

The voter access debate comes as the county, once known as “America’s most conservative large urban county,” has become more purple in recent years. President Joe Biden became the first Democratic presidential candidate to win Tarrant County since Lyndon B. Johnson in decades. Beto O’Rourke won the county in his failed 2018 bid to unseat U.S. Sen.Ted Cruz.

sent weekday mornings.

O’Hare won his seat as county judge in 2022, when the county also favored Gov. Greg Abbott’s reelection bid.

"Tarrant is one of the most diverse, electorally competitive counties in Texas,” said Texas Democratic Party Chair Gilberto Hinojosa. “Texas Democrats know it, and Tim O’Hare knows it, too. That’s why he is deliberately targeting early voting sites in high-turnout locations.”

GOP bid to remove polling sites from Tarrant County college campuses fails

During an emergency commissioners court meeting last week, county staff presented three lists of early voting locations, all of which included fewer colleges and total sites than in the past. About 10% of the ballots in Tarrant County during early voting in the 2020 presidential election were cast on college campuses, according to the county's data.

Days before, Tarrant County GOP Chair Bo French wrote in a newsletter that, “Having these locations denied is a serious win for Republicans in Tarrant County.”

But before county commissioners could vote on any of the three proposals, Ramirez called for a vote on a list of early voting locations that instead added a new polling site.

After four hours of public comment, O’Hare asked if Ramirez would amend his motion to carry one of three location lists county staff had presented. Ramirez declined, saying, “Reducing the number is not a priority.”

Texas GOP Chair Abraham George criticized the vote on social media, saying, “When Republican elected officials vote against their Republican constituents, they damage our brand and hurt our party.”

The resolution the Tarrant County GOP signed Friday calls on Ramirez and Ficke to publicly commit to supporting the county’s Republican leaders, promote election integrity and ensuring the party's success in the November election.

O’Hare, Sheriff Bill Waybourn, and District Attorney Phil Sorrells created last year a county election integrity task force to focus on potential voter fraud. It has yet to file any charges.

Ramirez responded to the resolution with a statement he sent to French, in which he defends last week’s vote.

“I took an oath to serve Tarrant County and defend the Constitution. To me, this includes ensuring free, fair, and equal access to voting in elections,” Ramirez wrote. “After prayer and reflection, I could not, in good conscience, support eliminating voting sites that served over 9,000 citizens in the last election.”

The first-year commissioner usually votes with the Republican majority on the commissioners’ court. He voted to pass the biggest tax cut in recent county history and to block funding to a nonprofit over concerns about its support of LGBTQ+ issues and abortion rights.

“Republicans win because we work hard and have the right message, not because we cheat,” Ramirez added.

Two Fort Worth Republicans, Mayor Mattie Parker and state Rep. Charlie Geren, defended Ramirez in social media posts.

“Democracy is meant to be an arena for ideas. When we resort to winning at the expense of voter turnout, we’ve all lost,” Parker wrote on X. “Manny Ramirez should be commended, not vilified, for doing his job and protecting our fundamental right to vote.”

Anthony Gutierrez, executive director of the voting rights group Common Cause Texas, said elections should be decided by the voters.

“While the Tarrant County GOP might wish otherwise, politicians abusing their power to alter the outcome of elections is not how our system for administering elections should work,” he said.

Disclosure: Common Cause has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

These Are the Right-Wing Ideologues Taking Over School Boards

Conservative consultants and PACs are turning Texas school boards into partisan battlegrounds.

A version of this story ran in the November / December 2023 issue.

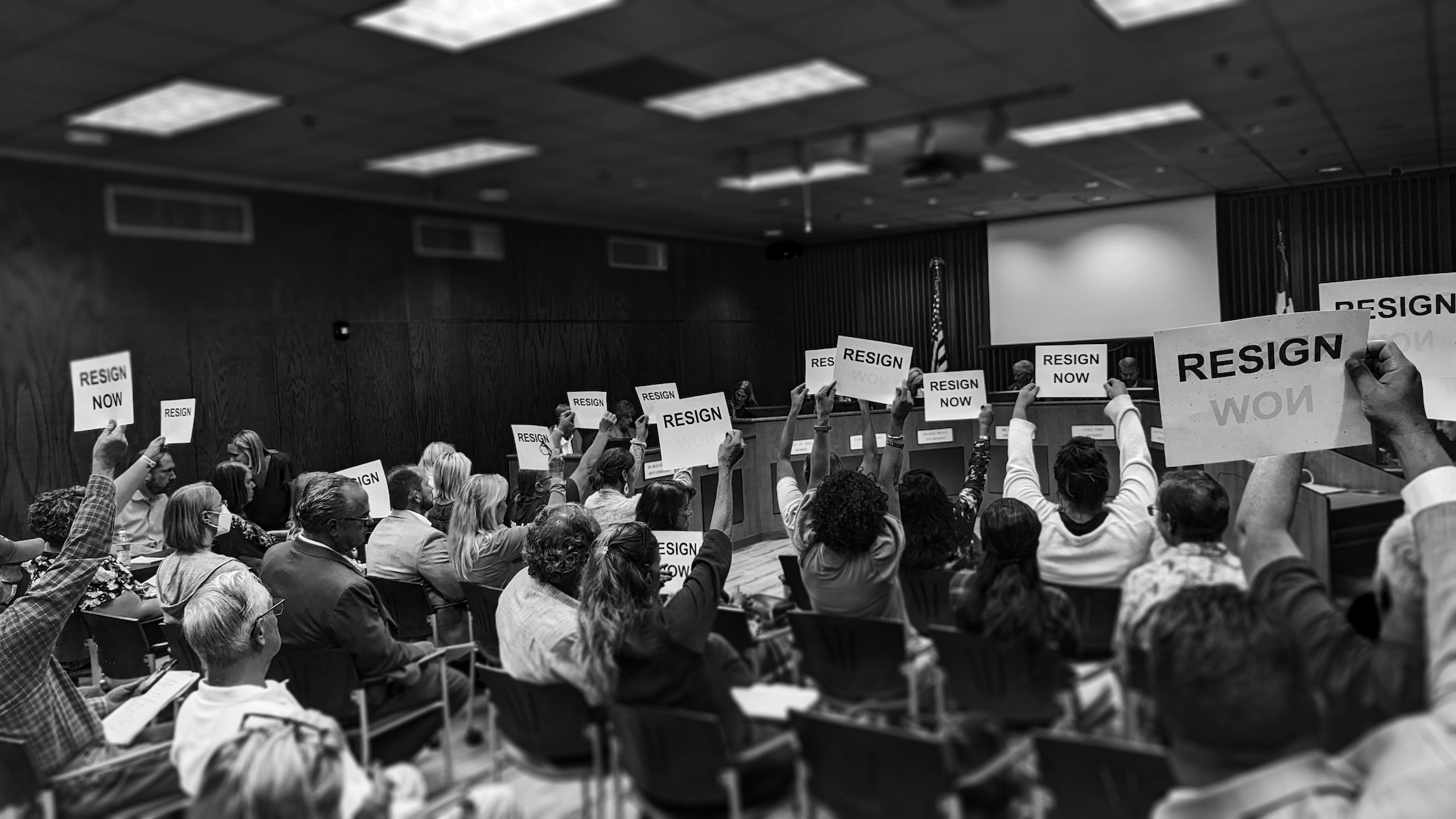

Above: Parents demand the resignation of conservative Grapevine-Colleyville School Board Trustee Tammy Nakamura.

Over the last three years, an interconnected network of political action committees (PACs), largely funded by billionaires who support school privatization, has begun to transform the nature of local school board elections across Texas. They’ve done this with the help of consultants whose efforts have largely gone unnoticed.

On August 15, 2022, members of the Carroll Independent School District (CISD) board of trustees, all dressed in Southlake Dragons’ green, posed for a photo with representatives of Patriot Mobile, a Christian Nationalist phone company that spent big last spring to help secure the victories of three trustees. The occasion honored the company’s donation of posters that read “In God We Trust.”

The trustee’s acceptance of the red, white, and blue star-spangled posters immediately drew opposition from critics who see those words not just as a motto that appears on dollar bills, but also as a declaration of allegiance to conservative causes. One disapproving parent attempted to donate signs with the same words in Arabic and on a rainbow background but was rejected; the board president said they already had enough.

Other school districts got the posters around the same time. And not all parents who spoke out were critical.

Erik Leist, who resides in the neighboring Keller ISD area, spoke to multiple news outlets about the posters after they were donated. He approved of the state law passed in 2021 that requires schools to display donated signs bearing the national motto in a “conspicuous place.”

“If it’s important to communities, the community will come behind it,” Leist said, according to accounts published in Fox News and the Texas Tribune that identified him only as the father of a kindergartener.

Leist, however, is much more than a concerned dad: He’s a conservative political consultant who at the time had already been paid tens of thousands of dollars by multiple PACs to support the campaigns of new ultraconservative school board members in Carroll and neighboring school districts, trustees who were eager to accept those posters and who later passed policies restricting students’ access to library books and rolling back accommodations for LGBTQ+ students.

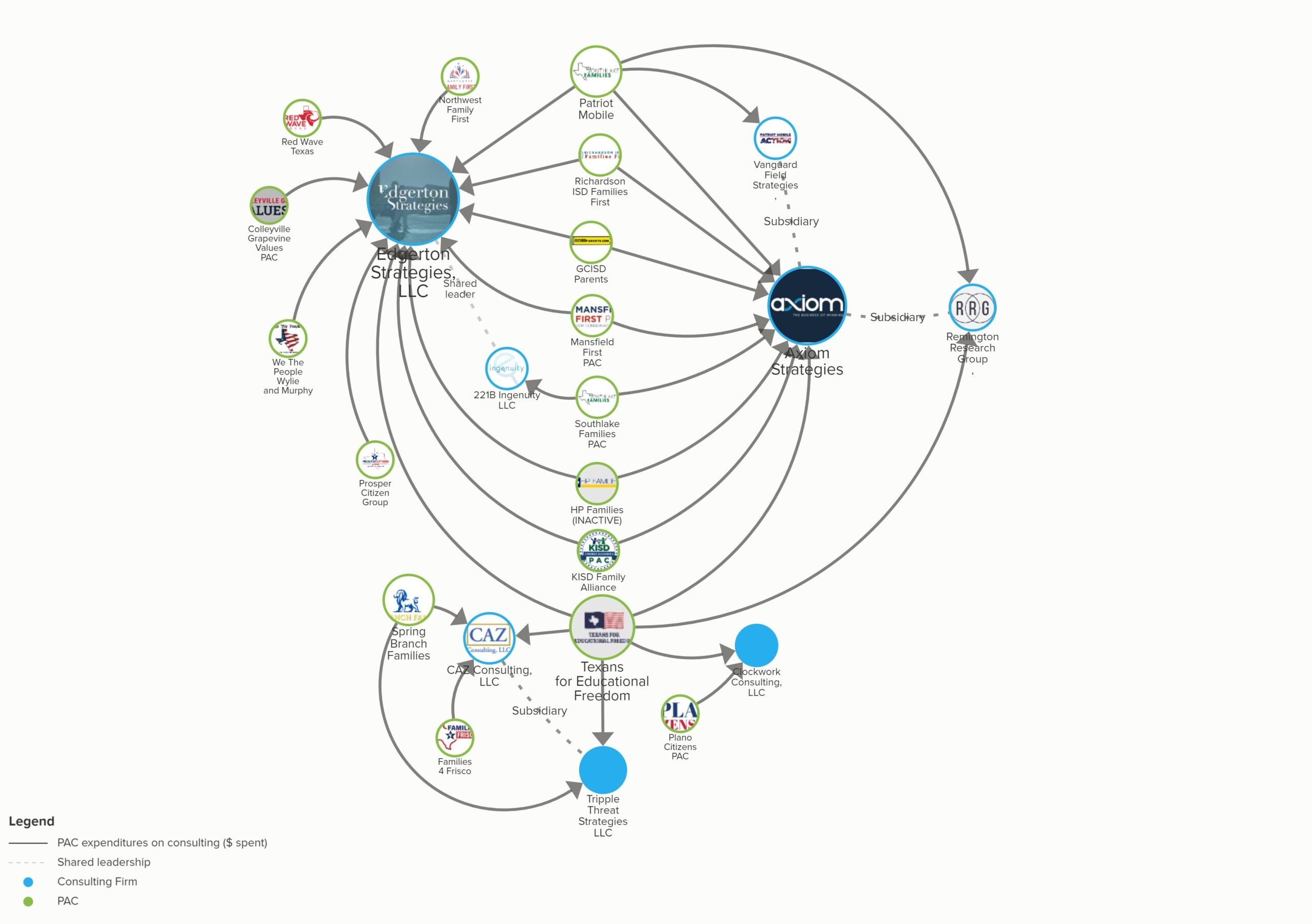

Leist is just one well-connected node in a sprawling, hydra-like network of PACs and consulting firms that increasingly are targeting Texas school board races and politicizing those formerly low-budget, nonpartisan campaigns, an investigation by the Texas Observer reveals.

The Observer’s examination of campaign finance records shows that dozens of ultraconservative school board candidates around the state have been backed by PACs that collectively employ a handful of conservative political consulting firms.

Viewed together, the connections among these individuals and organizations reveal a network of major funders and political operatives focused on winning control of the state’s local school boards. The strategy this network employs has been trumpeted in the right-wing press as a blueprint for school board takeovers: Create a PAC, endorse candidates willing to run on politicized issues, hire a consulting firm with ties to the Republican Party, raise enough to outspend opponents, and if victory is secured, pass policies that align with statewide party priorities. The biggest known backers of this network are conservative billionaires who generally don’t live in the districts being targeted but all of whom support school privatization efforts.

The timing of the network’s activities corresponds to revived efforts by Governor Greg Abbott and Republican lawmakers to support vouchers for private schools in the 2021 and 2023 legislative sessions.

The Texas Observer mapped out how this network of PACs, consultants, and funders are all linked together. Click above to interactively explore the network of connections.

To understand how this network developed over time, it’s best to begin in CISD—a district located in Southlake, a wealthy suburb of Fort Worth that is over 70 percent white. It’s where Leist got his start as a school board campaign consultant, supporting an effort praised by the conservative press as a model for other school districts.

In August 2020, the seven-member CISD board held a hearing on something called a Cultural Competence Action Plan, a proposal created in response to a 2018 viral video of Carroll high school students shouting the N-word.

Less than two weeks later, Tim O’Hare, the former chair of the Tarrant County Republican Party and current Tarrant County judge, teamed up with Leigh Wambsganss, a conservative activist and the wife of a former Southlake mayor, to create Southlake Families PAC.

In November 2020, Southlake Families PAC—which describes itself as “unapologetically rooted in Judeo-Christian values”—paid a Keller-based marketing company called 221b Ingenuity, of which Leist was a managing partner, to help set up a website to promote two conservative CISD school board candidates. They ran in opposition to the Cultural Competence Action Plan in the spring 2021 race that featured PAC-funded mailers accusing opponents of pushing “radical socialism.” Both PAC-backed candidates won.

In June 2021, the right-leaning National Review lauded Southlake Families’ victory as a “model for conservative parents confronted by similar situations around the country.” When Southlake Families helped a third candidate win a special election for a vacant CISD seat that fall, the three joined with a fourth PAC-endorsed incumbent to form a conservative majority on the board.

Since then, seven federal civil rights investigations have been opened into allegations of discrimination against Carroll students based on race, disability, and gender or sexual harassment. The most recent began in January 2023, one month after the board removed references to religion, sexual orientation, and gender identity from the district’s nondiscrimination statement, stoking further controversy and making news.

What has drawn less press attention is that the situation in Carroll has inspired a network of copycat PACs supporting conservative candidates in other historically low-budget nonpartisan school board races across the state, in which PACs and the candidates they endorsed hired from the same handful of consulting firms to help with campaigns.

Tentacles of this big-spending network have already reached more than two dozen Texas school districts. The Observer has identified 20 PACs formed since late 2020 that, through early September, have collectively spent more than $1.5 million to support the campaigns of 105 conservative candidates in 35 districts.

Most of the time, that investment has paid off: 65 PAC-supported candidates—or 62 percent—won their elections from 2021 to 2023.

The majority of those PACs are focused on only one school district each. The ultraconservative committees have typically spent tens of thousands of dollars per election, with less than $100,000 in total expenses since they were formed. A handful of PACs have spent more than six figures in total, including Southlake Families, which has spent more than $239,000 since late 2020.

Campaign finance records show that these seemingly grassroots groups often use the same consulting firms like Leist’s Edgerton Strategies, which has worked on behalf of PACs and candidates in at least 14 school districts. Other consulting firms that have made over six figures working on school board campaigns include Axiom Strategies and CAZ Consulting—and both companies’ subsidiaries. They’re the same consultants used by big-spending conservative political PACs like Patriot Mobile Action and Texans for Educational Freedom, which have respectively spent more than $500,000 and $330,000 on school board races and together have endorsed 66 candidates across at least 23 districts.

At least one federal-level super PAC, the 1776 Project, has also invested in 28 school board candidates across eight Texas school districts that were also endorsed by either Patriot Mobile Action, Texans for Educational Freedom, or one of the Southlake Families-style PACs.

This level of outside spending is highly unusual in school board races. The results of a 2018 survey conducted by the National School Board Association showed that 75 percent of all candidates reported spending less than $1,000 per race, with only 9 percent spending more than $5,000.

Analysis of campaign expenses by the nonprofit OpenSecrets shows that spending more money doesn’t always ensure victory—but often does. Given the relatively low cost of school board races, the influx of even a few thousand dollars of outside funding can transform the nature of such elections at a time of high turnover: According to a 2022 survey from School Board Partners, a national organization focused on recruiting and training anti-racist school board members, nearly two-thirds of school board members nationwide said they planned not to seek reelection.

This is extremely abnormal. This level of funding brings the possibility of raising the cost of being a legitimate candidate.

“This is extremely abnormal,” said Sarah Reckhow, a professor of political science at Michigan State University who has written two books about outside funding of school board elections. “This level of funding brings the possibility of raising the cost of being a legitimate candidate.”

Still, she said, if higher spending causes voters to be more engaged in low-profile elections and recognize that other people are influencing their school district, “then maybe that’s a good thing.”

In the southeast Texas city of Humble, another 2021 school board race became a quieter testing ground for a new conservative PAC. Unlike in Carroll ISD, there was no dramatic national coverage or clash over diversity and inclusion. The district, in one of Houston’s sprawling and forested northern suburbs, was the first foray into school board races for Texans for Educational Freedom, a PAC with a mission of “fighting against Critical Race Theory and other anti-American agendas and curriculums.”

Funded primarily by a coterie of conservative billionaires, Texans for Educational Freedom—originally known as the Freedom Foundation of Texas—was founded in early 2021 by Christopher Zook Jr., a former field director for the Harris County Republican Party and senior fellow at Texans For Lawsuit Reform.

In the May 2021 election, the PAC spent more than $10,000 to help three candidates—a significant investment from one source, given that Humble school board candidates tended to spend only about $3,300 from all contributors in contested races. The PAC money was spent on a national political consulting firm called Axiom Strategies. All three of the PAC’s candidates won.

Unlike in majority-white Southlake, the school board election in Humble—where white students are a minority—didn’t feature inflammatory, politicized rhetoric. That helped Texans for Educational Freedom keep a low profile.

“I wasn’t aware there was outside PAC spending,” said Brian Baker, a father of two students in Humble ISD. “I had been paying attention to stories in other parts of the state and I was looking out for candidates and mailers using certain buzzwords like ‘woke,’ but I didn’t really notice any.”

After the initial victory in Humble, Texans for Educational Freedom targeted two more districts near Houston, Cypress-Fairbanks and Klein, in 2021. This time, messaging around critical race theory came to the fore. All three PAC-backed candidates in Cypress-Fairbanks ran against the ostensible inclusion of critical race theory in school curriculum and teacher training, as did one PAC-backed candidate in Klein. Six of the seven candidates won.

By the end of 2021, candidates backed by Texans for Educational Freedom had established near or outright majorities in all three districts—and all three would later rank on a list of book-banning districts put together by PEN America, a nonprofit organization focused on the protection of free expression.

Texans for Educational Freedom has intervened in races across the greater Houston area, including Houston, Conroe, Katy, and Spring Branch. The PAC has also backed candidates in the wooded Austin suburb of Leander, in the oil-rich flats of Midland, in several suburbs of Fort Worth, and in the Panhandle’s Canyon ISD. The PAC backed 12 candidates in 2021, 10 in 2022, and 20 in 2023, covering a total of 17 school districts. Out of all those candidates, 76 percent won their elections.

“Things like this have happened before but not in such a coordinated way,” said Ruth Kravetz, a retired public school administrator and teacher who co-founded Community Voices for Public Education, an advocacy group that seeks to strengthen Houston’s public school system. “In the past it was to promote charter expansion. And now it seems like it’s about promoting the destruction of public education.”

Candidates backed by Texans for Educational Freedom have regularly run on hot-button issues that tie in with state-level Republican policy and rhetoric, such as notions that children are being “indoctrinated” into radical ideologies or “sexually alternative lifestyles.”

In Conroe ISD, three candidates backed by Texans for Educational Freedom ran as the “Mama Bear” slate and won their November 2022 elections after being involved in a push by a group known as Mama Bears Rising to restrict student access to certain books.

“The PACs were able to support a massive printing of voter guides and distribution of mailers,” said Evan Berlin, a resident who lost to one of the Mama Bears. Berlin, a first-time school board candidate who has a conservative voting record, told the Observer he wanted to run on providing education in a non-politicized manner. “I think with PAC money coming from out-of-district donors, just by nature of that we could assume that it’s part of a larger, more strategic effort,” he said.

Last year, while Texans for Educational Freedom was concentrating on Houston area races, Patriot Mobile Action and another 17 PACs were backing candidates in 22 districts across the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Those candidates largely ran on issues that have become a common refrain: allegations of ideological indoctrination, critical race theory, pornography in schools, and the sexualization of children.

Fifteen of the 18 PACs targeting North Texas school districts tapped either Axiom Strategies, Edgerton Strategies, or CAZ Consulting for campaign consulting—as did many school board candidates in the area. The outliers were: McKinney First PAC, which endorsed candidates that worked with those consulting firms; Metroplex Citizens for a Better Tomorrow and Decatur ISD Parents Unite, two groups primarily funded by a Republican mega donor who has contributed to Texans for Educational Freedom; and Collin Conservatives United, a self-described PAC that does not appear in the state PAC registry, whose endorsed candidates received donations from the same megadonor.

As this larger cluster of PACs and consulting firms has grown, its strategy has proved potent. Fourteen of its 17 candidates won in 2021. Another 42 candidates ran in 2022 and 27 won. And so far in 2023, 48 more candidates ran and 26 won.

By September 2023, PAC-supported candidates had established majorities in at least eight districts: Carroll, Grapevine-Colleyville, Humble, Katy, Keller, Klein, Mansfield, and Spring Branch. And these efforts are continuing.

The recurring appearance of certain consulting firms and big donors across supposedly nonpartisan school board races appears to have been planned or coordinated statewide, if not beyond. In December 2021, the Republican Party of Texas championed PAC-backed victories in Carroll and Cypress-Fairbanks school districts and explicitly stated the party’s intention “to play a greater role in non-partisan races and ballot propositions” and focus on recruiting and resource sharing.

“It is no coincidence that this initiative comes at the same time President Biden’s Department of Justice is attempting to suppress parental involvement in local elections by threatening to treat parents as terrorists for becoming involved in their children’s education,” wrote Texas GOP Chairman Matt Rinaldi. “Democrats across the country see the importance of local elections in the fight for America, and so does the Texas GOP.”

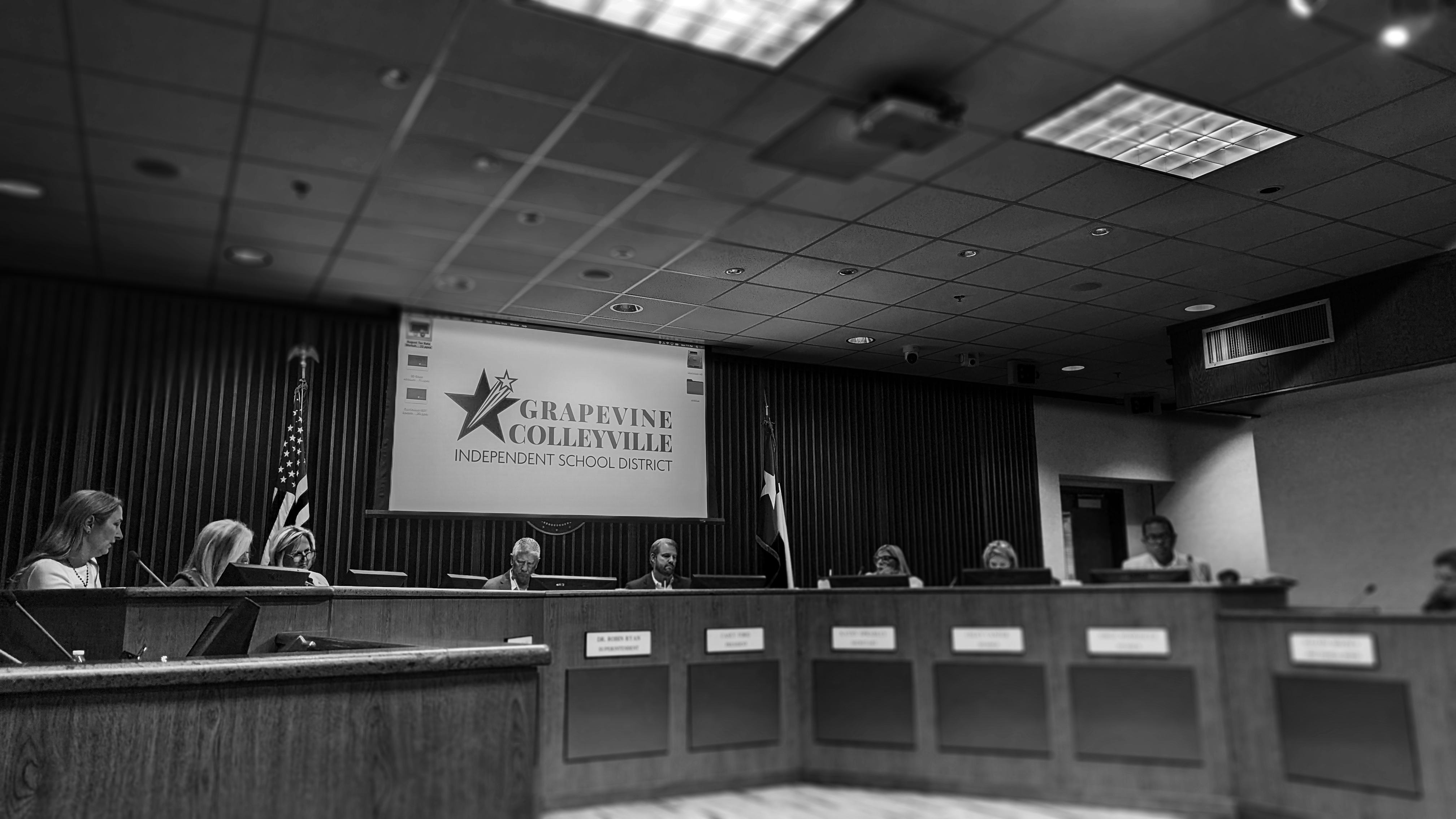

In August 2022, Shannon Braun, a Grapevine-Colleyville ISD (GCISD) trustee and current president of the board, wrote an opinion piece for the conservative website the Dallas Express titled “What Happened in GCISD Isn’t an Accident, It’s a Model.”

“I take comfort in knowing that none of this happened by accident. It was in fact a deliberate course of action that can be replicated in any community across Texas.”

“I take comfort in knowing that none of this happened by accident,” Braun wrote. “It was in fact a deliberate course of action that can be replicated in any community across Texas, so long as there are enough people willing to take a stand and take the heat that comes with it.”

Braun was endorsed in 2021 by GCISD Parents, a local PAC that as of 2023 had paid both Edgerton Strategies and Axiom Strategies for consulting services. Braun also directly hired Leist as a consultant and was endorsed by Wambsganss of Southlake Families PAC.

During her 2021 race, Braun spent over $30,000—more than three times her incumbent opponent—to defeat Mindy McClure, a long-time PTA volunteer and former Republican precinct chair.

“I didn’t see it coming,” McClure told the Observer. “But looking back, it’s clear to me that there was a lot of outside money and coordination. It made the race more political than local.”

Since her election, Braun has joined with other newly elected conservative school board members to pass policies that mirror statewide Republican priorities, including limiting how teachers talk about race, gender, and sexuality, and restricting bathroom access for transgender students.

Among Braun’s allies on the school board is Tammy Nakamura, a former Colleyville City Council member who endorsed Braun’s 2021 campaign. Nakamura’s 2022 school board candidacy was endorsed by GCISD Parents and Patriot Mobile Action and assisted by Edgerton Strategies.

The largest out-of-district donor to Nakamura’s campaign was Monty Bennett—the Republican mega donor publisher of the Dallas Express. Since 2021, Bennett has donated over $75,000 to candidates and PACs across seven school board races, including $7,000 to Texans for Educational Freedom.

Asked about his motivations for the donations, Bennett said, “Access to quality education should not be denied to any child, even when government can’t or won’t provide it.”

While Patriot Mobile Action is primarily funded with money from the Christian nationalist cell phone company, some conservative billionaires have forked over big bucks to school board PACs, including Houston real estate mogul Richard Weekley, who contributed $152,500 to Texans for Educational Freedom. He also gave $1,237,500 to the Coalition Por/For Texas, a PAC founded by Dallas real estate mogul Harlan Crow; the PAC transferred $150,000 of its funds to Texans for Educational Freedom. Then there’s Fred Saunders and his son Stuart Saunders of the wealthy Houston area banking family, who together have contributed $297,500 to Texans for Educational Freedom, and James Leininger, the Texas Public Policy Foundation founder and longtime school voucher proponent who donated $70,000 to Texans for Educational Freedom.

Bennett, Weekley, and Crow are all supporters of Texans for Educational Reform, an advocacy organization and PAC that has pushed for school privatization and vouchers since 2014.

McClure, the former GCISD trustee who was unseated by a PAC-backed candidate, believes that this seemingly coordinated effort to take over school boards has a larger agenda.

“There’s a lot of money in education,” McClure said. “I think it’s ultimately all an effort to support the push for school vouchers.”

This is about dismantling public education as we’ve always known it to exist by disrupting it from the inside.

Anne Russey, a parent of two children in Katy ISD schools, has been a vocal critic of the district’s new PAC-backed conservative majority.

“This isn’t just about gaining control over school boards,” Russey said. “This is about dismantling public education as we’ve always known it to exist by disrupting it from the inside.”

Where conservative school board majorities have been secured with the support of a similar set of PACs and consultants, trustees have passed similar policies.

In 2022, new PAC-backed conservative majorities passed a range of new policies in the Carroll, Mansfield, Keller, Klein, Spring Branch, and Grapevine-Colleyville districts, affecting things like access to certain books, the ability of LGBTQ+ students to use certain bathrooms, and how staff discusses issues of race, gender, and sexuality. In Frisco, where only two of four PAC-backed candidates won, the board passed a policy restricting transgender students from using their preferred bathrooms—spurring a complaint from the Texas chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union.

In June, PAC-backed trustees in Keller ISD voted to adopt controversial policies regarding pronoun and bathroom use, effectively requiring teachers to deny the chosen gender identity of students. And in late August, the Katy ISD board began requiring staff to inform parents if their children identify as transgender or choose to use a different name or pronouns at school.

“This policy is a direct assault on trans students and other marginalized groups of students who don’t have a sufficient voice in policymaking,” said Cameron Samuels, who graduated from Katy schools in 2022. “So many trans students spoke at the board meeting where they passed the anti-trans policy, including myself. But they ultimately passed the policy after four hours of public comment, which was not a surprise at all. That’s what they were elected to do.”

Samuels, a queer person who uses they/them pronouns, had been very active at Lake High School in organizing against the attempts to remove LGBTQ+-friendly books. As a freshman, they discovered that LGBTQ+ resources like The Trevor Project were blocked on the school internet, and with the help of the American Civil Liberties Union, they got it unblocked. Now a graduate, Samuels is the executive director of Students Engaged in Advancing Texas, a nonprofit they co-founded to help organize student advocacy in policy-making.

“Katy is following a trend that matches many other school districts in the state,” Samuels told the Observer.

Whether this political network will continue to expand its influence to more school board races is uncertain. Recent defeats of PAC-backed candidates in Plano, McKinney, Frisco, and Richardson suggest that organized grassroots opposition groups have prevented highly funded right-wing school board takeovers.

Tarrah Lantz, a longtime PTA volunteer and a former president of the Plano ISD Council of PTAs, looked at campaign finance reports from other school board elections in Tarrant County and knew what was coming when she decided to run for Plano school board in May 2023. Lantz sent out mailers about the threat of outside influence and called out a slate of three candidates who she said were working with “the same Keller-based campaign consulting firm as Patriot Mobile Action, a cell phone company with an extremist agenda which led the recent takeover of Keller, Southlake, Carroll and Grapevine-Colleyville school boards.”

“This was on my radar,” Lantz said. “I was watching what was happening across the state, and I knew that if I ran we would have a conservative effort that would try to put forth candidates to be mouthpieces for people who might not have a direct interest in Plano ISD.”

She was right. Payments to Edgerton Strategies and Axiom Strategies appeared on the campaign finance reports of all three conservative candidates endorsed by the Plano Citizens’ PAC, which also paid Edgerton for consulting work. All three candidates lost, but the races proved costly for the victors.

“We had to really treat it as if we were running a campaign for state or congressional house,” Lantz told the Observer. “We had big yard signs or big road signs. We had field operations. It was massive for a school board. Unprecedented, I would think.”

Ultimately, Lantz attributes her victory to being more education-focused.

“When asked about things like safety and security at one of the first candidate forums, while my opponent said they thought the alleged existence of pornography in the library was our biggest issue, instead I talked about the bond money we have committed to safety and security and the addition of doors that can create barriers should a shooter be inside a school,” Lantz said. “They were concerned with singular issues, or they were running with an agenda.”

Even as some recent efforts by this network have faltered, new fronts have opened in the battle for education. Some school boards taken over by ultraconservative majorities are not only adopting cookie-cutter policies, they are charting courses far out of the mainstream by trying to divorce themselves from the longstanding association that trains and supports state school boards.

On March 17, the Texas GOP called on school boards to disaffiliate from the Texas Association of School Boards (TASB), an organization formed in 1949 that supports school boards with training and shared resources. The reason: TASB’s guidance regarding accommodations for transgender and gender-nonconforming students. Just ten days later, CISD’s conservative-dominated board voted to break ties with TASB. The trustees later expressed interest in joining a new organization, Texans for Excellence in Education, an explicitly conservative, newly formed nonprofit alternative to TASB.

According to corporate filings in Delaware, Texans for Excellence in Education was founded in 2021 by Dallas hospitality industry entrepreneur Adrian Verdin, an associate of Bennett’s who has often visited Bennett’s ranch. The first article about Texans for Excellence in Education appeared in Bennett’s Dallas Express. The article named a longtime Republican political consultant as the group’s public affairs manager. The consultant has started multiple organizations in the past with Bennett, including an unsuccessful attempt to launch a school voucher program in Wimberley ISD. Bennett did not respond to specific questions about these ties.

Texans for Excellence in Education promotes something they call the “Classical Social Emotional Learning” policy, which targets social issues such as “critical race theory,” “gender fluidity,” and “potentially pornographic material.” The metadata for the policy document available on the Texans for Excellence in Education website shows it was authored by someone at the law firm that employs Tim Davis, the general counsel of the Tarrant County Republican Party. The policy was first considered by the GCISD board of trustees, which since 2022 has hired two firms where Davis has worked as a partner. In September, GCISD fielded a presentation from Texans for Excellence in Education after two trustee candidates endorsed by the organization won their elections.

State Representative Nate Schatzline, who represents part of Tarrant County and also has paid Axiom Strategies and Edgerton Strategies for campaign work, lauded Carroll ISD’s move and has promoted Texans for Educational Excellence in multiple social media posts.

“An alternative to [TASB] is finally here,” Schatzline wrote. “I’m calling on every Texas ISD to leave TASB and join Texans for Excellence in Education! They’ll provide all the resources your school district needs without the leftist indoctrination of TASB!”

There’s also a growing effort by some of these school boards with new PAC-backed conservative majorities to challenge long-standing school funding formulas. School boards in Carroll and Grapevine-Colleyville have recently considered resolutions opposing “recapture” payments to the state, while boards in Keller and Spring Branch have already passed them.

The recapture system, first put into law in 1994, requires local districts with high amounts of wealth per student to send excess local property tax dollars into a general fund that is redistributed to property-poor districts. Hence the system is often referred to as “Robin Hood.”

These resolutions, in the words of one PAC-backed CISD trustee, send a clear message to the state: “We’re not going to pay you, and that could come with some consequences.”

Chris Tackett, a former member of the Granbury ISD school board who has turned himself into a campaign finance researcher, fears that the parallel efforts of these right-wing school boards may ultimately undermine the schools they’re supposedly serving.

“People generally are happy with their schools, and that’s an obstacle to vouchers. … So while vouchers are being pushed … they have to devalue the community’s perception of their local schools at the same time,” Tackett said. “And I think that’s exactly what they’re doing.”

This story and infographic are part of a series supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Steven Monacelli is a freelance investigative journalist in Dallas. His reporting has been featured in Rolling Stone, The Daily Beast, The Real News, Dallas Observer, Dallas Weekly, and more. He is also the publisher of Protean Magazine, a nonprofit literary publication.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

How the ‘Southlake Playbook’ brought partisan battles to America’s school boards

The following is adapted from “They Came for the Schools: One Town’s Fight Over Race and Identity, and the New War for America’s Classrooms,” a book by NBC News senior reporter Mike Hixenbaugh set to be published by Mariner Books on May 14.

Three years ago, a conservative uprising swept through the wealthy, North Texas city of Southlake.

The impact of that local movement has since rippled well beyond the suburb’s borders — helping bring divisive political strategies to nonpartisan school boards across the country and quietly influencing what children are taught about race, gender and sexuality. As these conflicts continue to roil communities, the story of what happened in Southlake — and how it inspired conservative activists nationwide — reveals what’s at stake as voters consider competing visions for America’s schools in the 2024 election.

Southlake’s fight began after a series of racist incidents spurred local officials to roll out a plan to make the affluent Carroll Independent School District more inclusive. Then came the backlash.

In 2020, parent activists — outraged at what they depicted as anti-white and anti-American indoctrination — formed a political action committee called Southlake Families PAC, which promised to end diversity programs and elevate “Judeo-Christian values” at the suburban Carroll school district. They raised hundreds of thousands of dollars to support a slate of hard-line conservative candidates, launched attack ads accusing their opponents of being radical leftists and, in 2021, won control of the Carroll school board.

The landslide victories caught the attention of conservatives nationally.

Afterward, The Federalist, a conservative online magazine, compared Southlake’s political revolt to the early days of the tea party movement in 2010, when anti-Obama blowback propelled a new generation of far-right Republicans into power. “Only this time,” the magazine wrote, “the stakes are far higher, with conditions ripe for a new takeover.”

The Wall Street Journal editorial board praised the outcome in an op-ed titled “Southlake Says No to Woke Education,” writing, “Perhaps parents in other parts of the country will take the lesson that they can resist indoctrination that tells students they must divide and define themselves by race and gender rather than focus on learning and achievement.”

Laura Ingraham opened her nightly Fox News broadcast on May 3, 2021, with big news out of a small town in Texas. The clear message from Southlake, she told viewers of the “Ingraham Angle,” was: “We’re winning.”

Ingraham, like other Fox hosts, had spent months calling on her audience to fight the rise of Black Lives Matter and critical race theory in American society. “More of you are smartly heeding that call, because in Saturday’s election in Southlake, Texas, candidates opposed to the far-left BLM curriculum won the two open seats on the Carroll Independent School District board with nearly 70% of the vote.”

It may have been the first time that a Fox News prime-time program led with the results of a local school board election. Six months after former President Donald Trump’s 2020 election defeat, conservative pundits appeared hungry for something to celebrate — some indication that the political winds were shifting ahead of the 2022 midterms. After years of selling their viewers a dark vision of America besieged by sinister forces from the left, the Southlake story appeared to present the bosses at Fox News with an opportunity to feed their audience something markedly different: hope that their side would prevail.

Activist Chris Rufo, the man most responsible for turning critical race theory into a conservative battle cry, was so excited by the outcome in Southlake that he apparently failed to fact check his celebratory tweet: “In 2020, Joe Biden narrowly won this district. Today, anti-woke candidates won by 40 points,” Rufo wrote, conflating Southlake’s 2020 presidential results — which skewed heavily for Trump — with those of the broader, more moderate Tarrant County, whose electorate had swung narrowly for Biden.

Nevertheless, Rufo’s point was fast becoming conventional wisdom on the right: Southlake, the argument went, held the answer for how Republicans could regain the ground they’d lost over the years in fast-growing and rapidly diversifying suburbs nationally. Republicans believed they could motivate voters by recasting nonpartisan school board elections as fights for the soul of America.

Days later, former Trump adviser Steve Bannon declared on his War Room podcast: “The path to save the nation is very simple — it’s going to go through the school boards.” That summer, the Center for Renewing America, a leading think tank in a conservative consortium that’s now preparing for a second Trump administration, published a 33-page handbook for taking control of school boards, holding Southlake Families PAC up as a model.

The sense that the strategy was a winner for conservatives nationwide was also the headline message that spring when the leaders of Southlake Families PAC threw themselves a victory party at the home of Leigh Wambsganss, a longtime local conservative activist and one of the political action committee’s co-founders.

The chairman of the Texas GOP, Allen West, had come to celebrate their success — and issue a challenge.

“This is a best practice,” he said. “This is a lesson learned. You have to put this in a white paper. You have to make a video. You’ve got to make sure that you export this to every single major suburban area in the United States of America.”

West paused between those words for emphasis: Every. Single. Major. Suburban. Area. In the United States.

In August 2021, 17 months after the initial shutdowns to prevent the spread of Covid, a disturbing scene unfolded in a darkened parking lot outside a school board meeting in Williamson County, Tennessee, a wealthy and predominantly white community in the suburbs south of Nashville.

As the Delta variant of the coronavirus burned through the population that summer, filling hospital beds across the nation, the school board in Williamson County had made the politically divisive decision to follow the advice of public health experts and reinstate the district’s mandatory mask policy for the upcoming school year.

After the vote, an angry crowd swarmed mask proponents as they headed to their cars. “Take that mask off,” a woman shouted, getting into the face of another resident. Later, two men followed a mask-wearing official to his car, shouting, “We know who you are!”

“You can leave freely,” one of the men yelled, “but we will find you!” The other man made the threat more explicit: “You will never be allowed in public again!”

Video of the altercation went viral on social media, becoming the latest in a line of chaotic school board meetings to make headlines that summer, as conservative parents nationwide revolted against pandemic safety measures and lessons on racism that they attacked under the right’s ever-expanding definition of critical race theory.

Similar scenes had played out in Loudoun County, Virginia, where parents opposed to a district diversity plan shut down a meeting chanting, “Shame on you!” and in Rockwood, Missouri, where a school superintendent felt compelled to hire private security to stand guard outside the homes of Black senior administrators responsible for overseeing the district’s diversity and inclusion programs.

Your shortcut to understanding public schools across the U.S.

Whether you're an educator, parent, or informed taxpayer, our free national newsletter is for you. Get a weekly digest of everything you need to know about public education this week.

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Notice and European users agree to the data transfer policy. You may also receive occasional messages from sponsors.

School board meetings grew so volatile that summer and into early fall that the National School Boards Association wrote a letter to President Joe Biden requesting help assuring the safety of school employees and board members. Attorney General Merrick Garland followed up by sending a memo to the FBI and federal prosecutors noting a “disturbing spike in harassment, intimidation, and threats of violence” against school officials, and directing agency leaders to come up with strategies to address those concerns.

Conservative activists seized on the missive to spread a conspiracy theory that the Justice Department planned to target parents opposed to critical race theory and to prosecute angry suburban moms as “domestic terrorists.”

Many conservative parents embraced that title as a badge of honor that summer as they rallied around new national groups like No Left Turn in Education and Moms for Liberty that had formed to take the fight to school boards.

Robin Steenman had launched a Moms for Liberty chapter to oppose the mask mandate and lessons on racism in Williamson County, the site of the ugly parking lot showdown. An Air Force veteran and white mother of three, Steenman’s own children did not attend public school, but as a taxpayer in the Nashville suburb, she was determined to rid the district of any lessons or curriculum that she believed focused too heavily on the history of racism in America.

Although Steenman said she admired Martin Luther King Jr.’s call to judge others based only on the “content of their character,” she and her supporters wanted the district to ban the children’s book “Martin Luther King Jr. and the March on Washington,” because it contained historical images — including depictions of white firefighters blasting Black people with hoses — that might make white children feel bad about themselves.

“There’s so much positive that has happened in the 60 years since,” Steenman told a Reuters reporter, referring to several historical books she wanted removed. “But it’s all as if it never happened.”

The district refused to remove the books, arguing that they presented important historical facts in a clear, age-appropriate format. Later, the school board agreed to minor adjustments in the way teachers presented some of the material, but that did not appease Steenman, who’d come to believe that speaking at board meetings and writing stern letters wouldn’t be enough to effect real, lasting change.

If she and her supporters were going to take control of their public schools, they would need to harness the anger on display at public meetings that summer to win seats on the school board itself.

To do that, Steenman looked to the example set in a Texas town some 700 miles away.

In October 2021, five months after Southlake Families PAC’s landslide election victory, Steenman filed paperwork to form a new political action committee of her own. She and her allies named it Williamson Families PAC and quickly launched a website, which featured a mission statement taken nearly word for word from SouthlakeFamilies.org.

“Williamson County is built upon the rock of Judeo-Christian values that are the foundation of our country. We welcome all that share our concerns and conservative values.”

Steenman confirmed her inspiration in an interview with The Tennessee Star, a conservative online news site: “Williamson Families is a recipe that’s been done before. It was done in Southlake, Texas,” she said. “So I said, ‘Wow, that really works. That could really work here.’”

Like Southlake Families, Steenman’s political action committee held a kick-off celebration. Instead of Allen West, theirs featured John Rich, a popular country singer known for supporting Republican politicians. And like the Texas-based PAC that inspired it, Williamson Families quickly raked in nearly $200,000 and set its sights on recruiting candidates for the following year’s school board elections.

As in Southlake, Steenman and others on the PAC privately interviewed prospective candidates, looking to weed out those who were insufficiently conservative. The Williamson County-based PAC also hired a heavy-hitter GOP consulting firm called Axiom Strategies — the same firm advising Southlake Families. Axiom, known for its work on Republican Sen. Ted Cruz’s presidential campaign and Glenn Youngkin’s campaign for governor that fall in Virginia, was now in the business of bringing sophisticated, national-level political strategies to local school board races.