~~ recommended by emil karpo ~~

Punta Arenas is at the intersection of changing shipping routes, new industries like green hydrogen, and the race for Antarctica. The U.S. and China have noticed.

BY PATRICIA GARIP | APRIL 23, 2024

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JOSÉ MIGUEL CÁRDENAS

This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Latin America’s ports | Leer en español | Ler em português

PUNTA ARENAS, CHILE — Perched on the pylons of a century-old coal pier, sleek black cormorants gaze out at cruise ships, propane tankers and research vessels dotting the white-capped Strait of Magellan. Farther into the horizon, a humpback whale blows a misty plume toward the sky.

This is a postcard from the end of the world, postmarked Punta Arenas.

But it’s not as remote as you might think.

Punta Arenas has become an unlikely hotspot for global shipping, one of several seaports gaining importance today across Latin America and the Caribbean. As wars choke vital shipping lanes in the Middle East and Europe, climate change snarls the Panama Canal and technological breakthroughs such as green hydrogen come to the fore, even ports on the region’s periphery are getting new attention from governments, multinational companies and others.

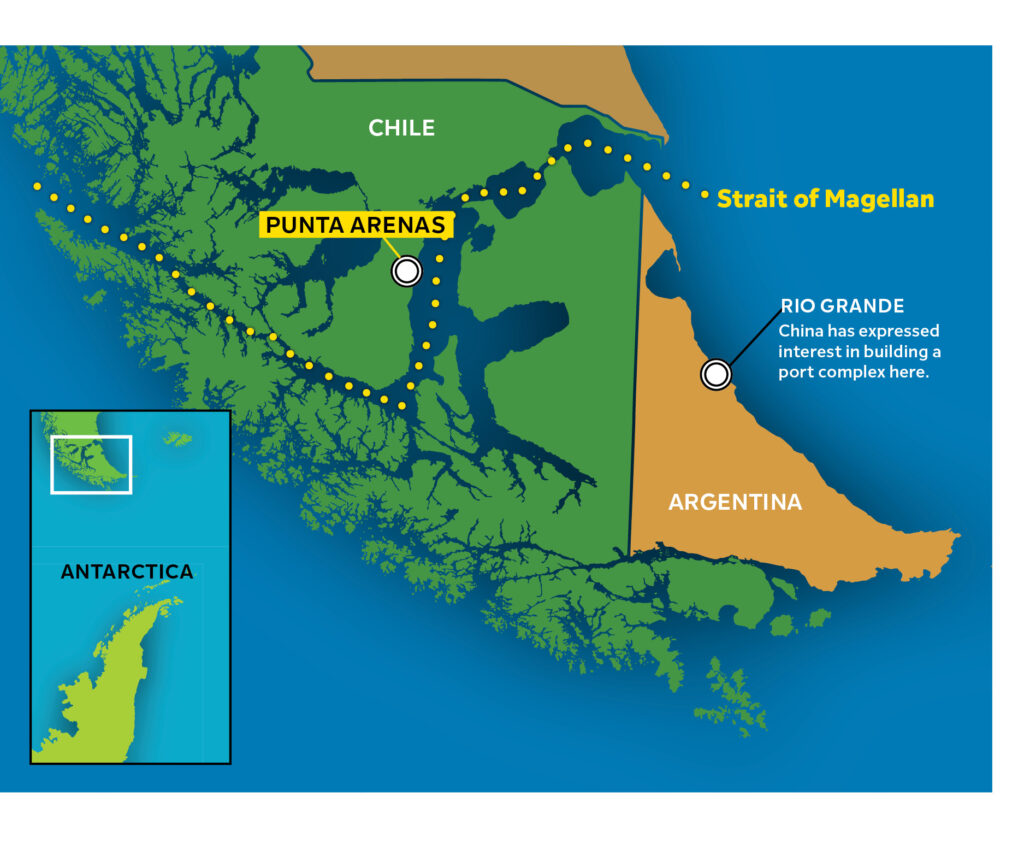

The changing tide is reflected in the soaring volume of merchant ships crossing the Strait of Magellan. In January and February, traffic jumped by 25% from the same period in 2023, and by 83% compared with 2021, when supply chains were still disrupted by the pandemic. Chile’s navy is bracing for this year’s traffic to increase by as much as an additional 70%.

“We’re in a part of the world that’s increasingly strategic, and it transcends the country,” Punta Arenas Mayor Claudio Radonich told AQ.

Global powers are racing to expand their presence. China has expressed interest in building a port complex near the Strait’s Atlantic mouth just across Chile’s border in Argentina. From there, Beijing could grow its presence in the region and also project influence in Antarctica, where geopolitical rivalry is heating up as the sea ice melts. In April 2023, the head of the U.S. military’s Southern Command, General Laura Richardson, visited Argentina and Chile, stopping in Punta Arenas for a security briefing and a tour of the strait.

“For Magallanes, this will be like going back in time, when we were a free port and ship traffic was enormous.”

—María José Navajas, regional director of Corfo

To properly seize the moment, Punta Arenas and the surrounding Magallanes region desperately need an infrastructure upgrade. At present, the region only has a few jetties and ramps, capable of receiving midsize vessels, some cruise ships and barges—but not large tankers and container vessels of the kind increasingly sailing through the strait. There are no loading cranes or protected basins. Even the navy lacks a port of its own here.

“If we want to move toward more just and inclusive development, we need more and better ports,” Chile’s President Gabriel Boric declared last October at the signing of a port expansion plan in Valparaíso. He lauded the “extraordinary modernization” of ports he had visited in China the previous week. Boric, who grew up in Punta Arenas, signed a $400 million, five-year investment program in November to upgrade ports and other infrastructure in Magallanes. But some wonder if it will be enough.

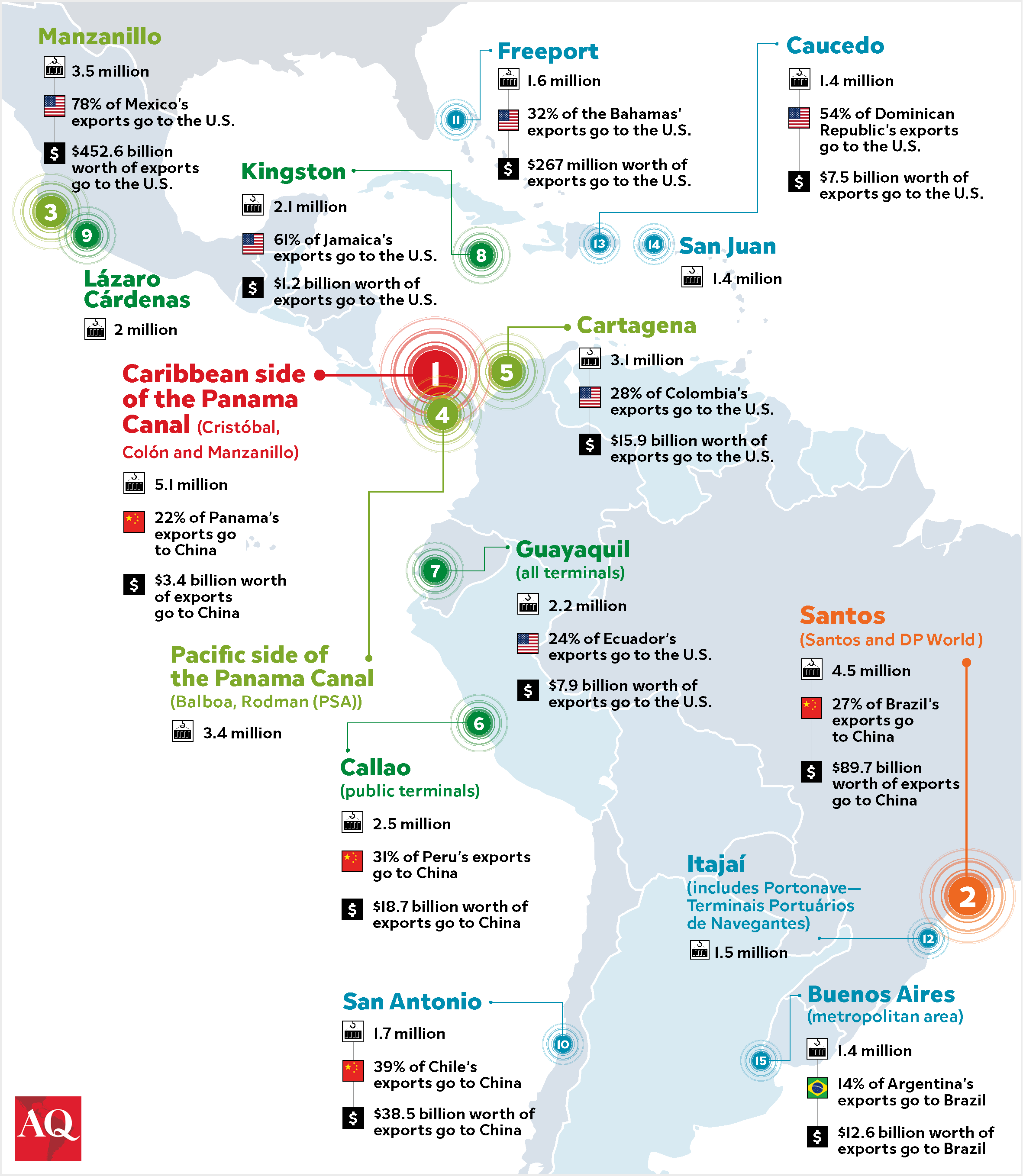

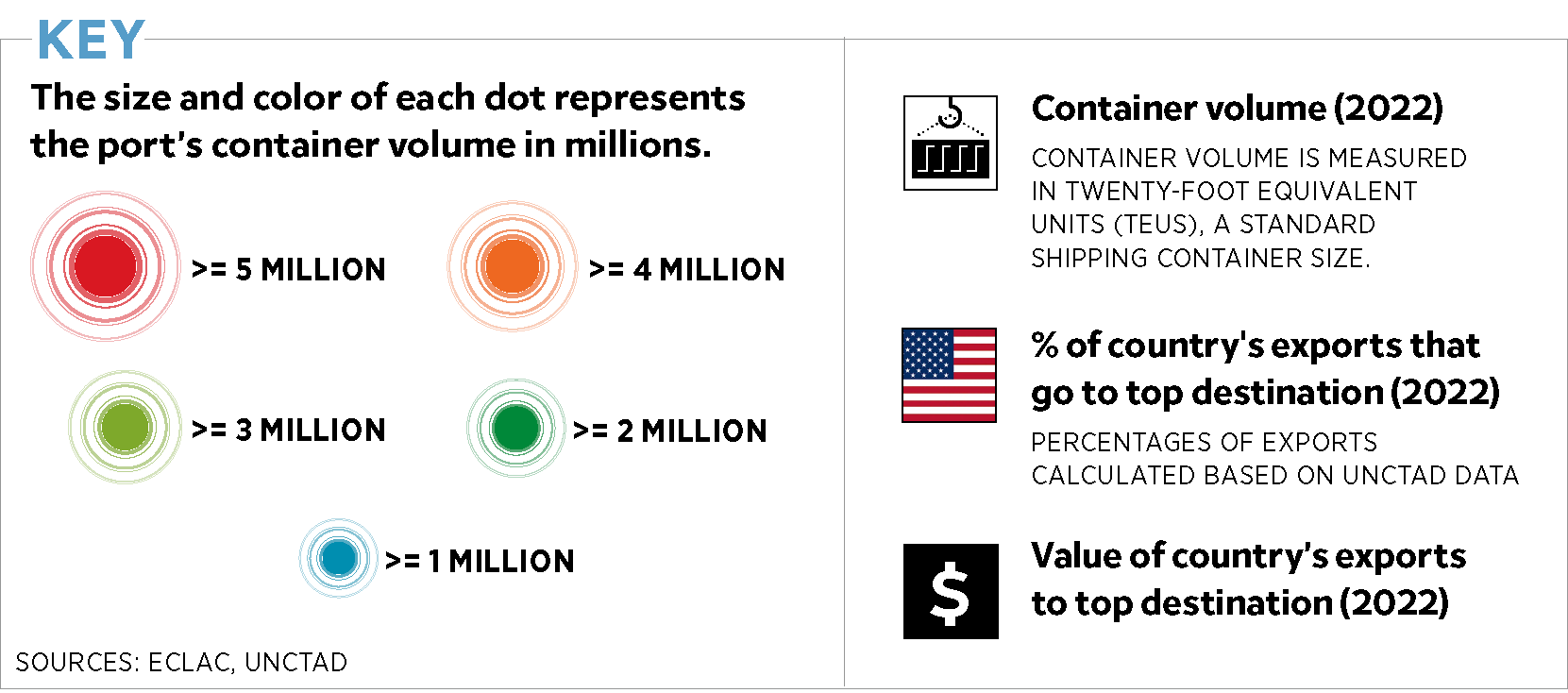

Indeed, investment is lagging in ports across much of Latin America and the Caribbean. Alarms were ringing as far back as 2018, when regional development bank CAF determined that the region needed $55 billion in maritime and ports investment by 2040.

Since then, progress has been limited. Montevideo is currently undergoing a $500 million expansion that will more than double international cargo volume. Oil-rich Guyana is building out Georgetown. The biggest project is in Peru, where Chinese state-owned Cosco Shipping will soon debut the first phase of its $3.5 billion Chancay seaport near Lima. Many other ports, like Ecuador’s Guayaquil, Brazil’s Santos and Chile’s San Antonio, remain dogged by inefficiencies and capacity constraints—as well as rising organized crime as cartels battle over lucrative smuggling routes.

The challenge is less about bricks than innovation. Most of the region’s ports are stuck in closed, outdated structures, the Inter-American Development Bank noted last year. Among the priorities are enhanced governance, digitalization and artificial intelligence to better predict and manage the flow of goods.

LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN’S BUSIEST CONTAINER PORTS

SQUARE ROOTS

The traffic surge through the strait, a 380-mile interoceanic waterway that roughly resembles the mathematical symbol for square root, largely reflects disruptions elsewhere.

Drought has sapped water levels in the Panama Canal, where monthly transits have halved from their December 2021 peak, UNCTAD reported in February. In the Red Sea, Iran-backed Houthi rebels have been firing missiles at ships since last year, slashing Suez Canal crossings by 42% over the last two months. And in the Black Sea, shipping is tenuous because of Russia’s war in Ukraine. The turmoil has forced shippers onto longer alternative routes.

Among the vessels resorting to the strait are bulk carriers, gas tankers and container ships. In recent years, traffic has been compounded by giant Chinese fishing fleets.

The surge poses a test for the navy, part of whose role is overseeing maritime safety. As in other waterways, navigational pilots, former naval officers in Chile’s case, deploy aboard all ships traversing the strait, while convoys accompany the Asian fishing fleets.

Accidents are rare, and the navy is determined to keep it that way.

“We can handle the traffic increase now, but if it continues, we’ll need to grow, both in infrastructure and personnel,” navy Commander Felipe González Iturriaga, the recently posted maritime governor of Punta Arenas, told AQ. “We’ll need more pilots, more people, and more resources to better control traffic with patrol boats.”

The rising traffic is reminiscent of a golden age etched onto neoclassical architecture around the leafy central square of Punta Arenas, the Magallanes regional capital. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the young Republic of Chile strove to reinforce its sovereignty in Magallanes, heeding a deathbed plea by founding father Bernardo O’Higgins. Croatian and Spanish immigrants and Chileans from Chiloé island settled here, drawn by coal and gold mining, a customs-free port and lucrative sheep and cattle ranching.

When the Panama Canal opened in 1914, the local economy dimmed. But Magallanes clung to its relative prosperity, especially after oil was discovered in the 1940s. National oil company Enap imbued local culture for generations. But most of the hydrocarbons turned out to lie in Argentina, with which Chile nearly fought a war in 1978 over disputed islands in Cape Horn. Along scenic Route 255 that hugs the Strait, you can still spot army bunkers and warnings about land mines dating back to this tense era.

In the decades since, Magallanes has neglected the sea, lamented eminent historian Mateo Martinic at his book-lined home in Punta Arenas. Chile now has a duty “to ascribe to the Strait of Magellan the significance and attention that it needs” through new port infrastructure that reflects its “extraordinary geopolitical value.”

GREEN GOLD RUSH

The modern economic anchor for Magallanes could become green hydrogen. The versatile carbon-free resource, derived from water using renewable energy, may eventually help to replace planet-warming fossil fuels. In the International Energy Agency’s ambitious net-zero scenario issued last year, the global market for low-emission hydrogen could balloon from just $1.4 billion today to $112 billion in 2030. It’s a bold scenario for a resource that’s yet to prove commercially viable.

Developers are undaunted. With fierce winds and a sparse population, Magallanes is a Goldilocks place to produce green hydrogen. The region has attracted at least 16 gigawatt-scale project proposals, mostly for export in the form of ammonia and synthetic fuels, or e-fuels, that recycle carbon dioxide.

Nearly all the aspiring producers are European companies rushing to meet EU mandates intended to slash emissions and diversify away from Russian gas. The project roster totals upwards of 3,600 wind turbines representing around 25GW of installed capacity. Realistically, four or five projects could crop up by the turn of the decade, enough to transform the landscape.

“For Magallanes, this will be like going back in time, when we were a free port and ship traffic was enormous,” said María José Navajas, regional director of state development agency Corfo. From shared infrastructure to a planned $6 million technology center in Punta Arenas, hydrogen’s advent “will be focused on the well-being of the whole region.”

Some executives are wary of potential liabilities from legacy installations that were built decades before today’s rigorous environmental evaluations.

That hopeful vision will only materialize with seaports, first to enable imports of equipment for turbines, electrolyzers, desalinization plants and other installations, and then to facilitate exports to markets like Germany and Japan.

Encouragingly, Chile has signed cooperation agreements with world-class ports in Rotterdam, Antwerp-Bruges and Singapore. And multilateral financing for infrastructure is within reach. “Wars are won with logistics, not guns,” quipped chemical engineer Erwin Plett, one of Chile’s green hydrogen champions.

STATE COORDINATES

On a gusty summer day in February, the Laurence M. Gould, one of two U.S. icebreakers permanently based in Magallanes, was snuggled across from Ukraine’s yellow-peaked research ship Noosfera at the Arturo Prat jetty in Punta Arenas. A cruise ship too big to dock there was anchored farther away, its passengers ferried ashore on tender boats.

State-owned Empresa Portuaria Austral (EPA) is gradually lengthening the 373-meter jetty to accommodate more research vessels and larger cruise ships. A few miles north at the José de los Santos Mardones cargo and cruise ship terminal near a navy shipyard, EPA plans reinforcements, two mobile cranes and a basin for safer disembarkation. All cruise ships will shift to Prat to free up Mardones for hydrogen-related imports.

Three years ago, Mardones handled imports for an e-fuels demonstration plant spearheaded by Highly Innovative Fuels (HIF), a consortium led by Chilean firm AME along with Porsche, U.S. fund EIG , Baker Hughes and Gemstone Investments. Located about 25 miles north of Punta Arenas, the tidy Haru Oni plant dispatched its first nominal e-gasoline shipments to Europe through Mardones, too. “From the public-sector perspective, we want to ensure that projects like HIF’s are not impeded by a lack of adequate infrastructure,” EPA chairman, Gabriel Aldoney, told AQ.

But Mardones is just a stopgap. The jetty is at least an hour’s drive along a narrow highway from wind farm sites, a precarious journey for delicate oversized equipment like giant turbine blades.

A closer, near-term option is Enap’s brownfield Laredo terminal near Haru Oni. In April 2023, Enap signed a $50 million agreement with hydrogen developers HIF, AustriaEnergy’s HNH Energy and France’s Total Eren to reconfigure Laredo’s ramp and esplanade for equipment imports and storage. One constraint is a shallow approach that would require inefficient barges.

The water is deeper at the adjacent Cabo Negro terminal where Enap has two active jetties. It uses one for cabotage fuel shipments and leases the other to Canadian methanol producer Methanex. HIF intends to install its first $830 million commercial-scale e-fuels facility in Chile at Cabo Negro, to be powered by the planned 384MW Faro del Sur wind farm, a $500 million project with Italian firm Enel Green Power. Between Laredo and Cabo Negro, there’s potential for another jetty at Punta Porpesse.

Enap has bolder plans for its Gregorio terminal, an hour north of Cabo Negro at Puerto Sara. The company and six developers—Total Eren, HI F, FreePower, EdF, RWE and HNH Energy—are studying this alternative and considering forming a consortium.

For potential partners, Enap offers obvious advantages. Its existing maritime concessions and right-of-way pipeline permits would expedite construction. And when it comes to red tape, having a state-owned partner is often a plus. But some executives are wary of potential liabilities from legacy installations that were built decades before today’s rigorous environmental evaluations.

Enap is cautious too. “We want to embrace this opportunity and be as business-friendly as possible, but this is an industry that globally still hasn’t taken off,” said CEO Julio Friedmann, who vowed to avoid “irresponsible business decisions or wishful thinking.” Meters from Haru Oni, the company is drilling a new unconventional gas well, underscoring its core business.

“Strategically, part of the navy’s role is to contribute to the country’s development.”

—Chilean Admiral Jorge Castillo

HARD TO SHARE

Comprehensive logistics plans are progressing, maintains Alex Santander, the Energy Ministry’s head of strategic planning and sustainable development. “You won’t see any fireworks, but we’re doing what we need to do, slowly but surely.”

The Boric administration wants seaports to be open access and shared among developers to minimize impact in a region rich in fauna like guanacos and condors. But it also wants to encourage job-creating industrial development.

As if that balance wasn’t tough enough, it’s uncertain whether developers will succeed in striking a deal to share infrastructure. The big ones are jockeying for early mover advantage, subsidies and the Holy Grail of offtaker deals. Executives also worry that cooperation would sow false perceptions of collusion.

In Chile, the shared model is unusual. In its mining industry, for example, ports are typically built by a single company for its sole use. And questions around who would operate a shared facility—Enap or a specialized third party, for instance—remain unanswered. “The main challenge behind shared infrastructure will be the business model,” said Aldoney.

The developers are going it alone for now. HNH Energy is eyeing a greenfield terminal at San Gregorio. Total Eren is targeting Posesión near the Strait’s Atlantic mouth where Enap has gas-processing facilities. On Tierra del Fuego Island, Danish fund CIP, Saudi fund Alfanar and U.K. company TEG could use Enap’s old Clarencia and Percy terminals at Gente Grande Bay.

In nearby Inutil Bay, German firm GSTF wants to install an offshore wind farm to make sustainable aviation fuel. While the trailblazing project would require less port infrastructure, a nearby penguin colony will make it harder to secure an environmental permit, even though subsea foundations are known to attract marine life.

How Chile navigates such environmental sensitivities will largely determine the pace and breadth of investment. The companies say their projects are compatible with nature and will help to decarbonize the planet. But obtaining myriad permits on top of maritime concessions is a complex, years-long affair. Any proposed dredging would prove especially thorny.

The administration says it is working to streamline permitting without compromising the environment. That doesn’t convince people like Ricardo Matus, who runs a bird rehabilitation center in Punta Arenas. “It’s like everyone wants to throw a party and Chile is putting up the house,” he told AQ. He worries that unbridled development will doom fragile species like the Magellanic plover and ruddy-headed goose.

So far, only HIF has submitted a permit application for its Cabo Negro project, after withdrawing an earlier one because of blowback over the potential impact of turbines on migratory birds. (In October 2022, HIF and partner Enel Green Power said public agencies “exceeded the usual standard” in assessing their hydrogen-associated wind project. They cited these “exceptional requirements” for the application withdrawal, rather than specifically referencing birds.) Other developers plan to apply by year’s end.

ROUGH SEAS

Permitting aside, the Strait’s rough conditions will make it difficult and expensive to build and operate jetties that could extend for more than a mile and a half. While the waterway doesn’t experience the imposing swells that regularly pause Chile’s Pacific ports, tidal ranges are among the world’s widest, up to 12 meters (39 feet) at the Atlantic mouth compared to an international open-coast average of around two meters (6.5 feet), according to seaports consultancy PRDW. Associated currents in the Strait’s narrows can hit a dizzying eight knots.

In the Otway Sound that bulges north from the Strait’s Pacific approach, the sea is calmer. This is where Chilean shipping company Ultranav plans to repurpose the jetty of a former coal mine on Riesgo Island. Ultranav’s Otway Green Energy would make use of an existing maritime concession to import hydrogen equipment, export ammonia and foster a green shipping corrider. The project would repurpose the site of the Invierno mine, which environmental opposition forced to close in 2020. Across the sound, the old Peckett coal mine offers a similar port option.

These sites are reminders of the boom-and-bust cycles that Magallanes has endured for generations. So locals are expectant but wary as foreign executives scope out the steppe. At the gravel turnoff for the village of Punta Delgada in San Gregorio municipality on Route 255, just past dwindling gas-producing blocks and the ghost town of a former sheep ranch, a windsock flaps over a new helipad. Streets around the village square are freshly paved and a new community center is going up. “We’ve been through this before. Look what happened with gas,” mused former sheep shearer Fredy Barria. “We have to be realistic, not optimistic.”

MAGALLANES MOMENT

On Argentina’s side of the Strait, investors are also weighing hydrogen and port opportunities as libertarian President Javier Milei steers a course more aligned with the West.

Chinese company Shaanxi’s proposal to build a $1.25 billion port at Rio Grande has been quashed by federal authorities, said international security expert Juan Belikow. For now, an Argentine contractor is designing a port for the site instead. Farther south, in Ushuaia, Argentina’s navy is expanding a base for Antarctic logistics and monitoring Chinese fishing.

Back in Punta Arenas, Magallanes Governor Jorge Flies sweeps his hand across a wall map of this proud region around the size of New Zealand, but with a mere 1% of Chile’s population of 19 million. In nooks beyond the Strait, Flies points to Ultima Esperanza Bay for Pacific-facing exports. In Puerto Natales and Puerto Williams, the hemisphere’s southernmost city, port works will encourage tourism.

The mandate transcends the commercial logic that drives seaports elsewhere in Latin America. A solid jetty in Chile’s slice of Antarctica is in progress, and designs are underway for a $200 million navy port near Mardones, Flies told AQ. “To have secure transit, and everything that’s needed for logistics and oversight, we need to have very strong armed forces.” A new authority incorporating the navy and EPA will oversee the future ports system.

A reinforced military presence here would help to safeguard freedom of navigation and Western access to Antarctica, an emerging theater of international competition over potential minerals exploration, fresh water reserves and defense dynamics. Also at play is global food security, embodied by green hydrogen-based fertilizers and a proposed grains terminal in Tierra del Fuego.

Chile’s naval leadership conveys commitment. “Strategically, part of the navy’s role is to contribute to the country’s development,” Admiral Jorge Castillo told AQ at the Third Naval Zone headquarters in Punta Arenas. “We should contribute by ensuring that this advances, and not be an obstacle, by allowing maritime industry to scale up in line with the needs of these new strategic situations.”

Flies captures the implications of this transformative moment for Magallanes. “Our role, our relative weight inside our country, and our global geostrategic significance will change significantly.”

No comments:

Post a Comment