1). “Notes from the Editors”, (First Entry – Discussion of Various Statements by Richard Haas), The Editors, Monthly Review, April 2024 (Volume 75, Number 11), at < https://monthlyreview.org/

2). “China is winning the battle for the Red Sea: America has retired as world policeman”, Feb 11, 2024, Nathan Levine, UnHerd, < https://unherd.com/2024/02/

3). “The Red Sea Crisis Proves China Was Ahead of the Curve: The Belt and Road Initiative wasn’t a sinister plot. It was a blueprint for what every nation needs in an age of uncertainty and disruption”, Jan 20, 2024, Parag Khanna, Foreign Policy, at < https://foreignpolicy.com/

4). “As Red Sea shipping attacks continue, pressure grows for China to act”, February 13, 2024, Nong Hong, ICAS, Originally published at South China Morning Post, at < https://chinaus-icas.org/

5). “How Houthis threaten US control over global shipping: A powerful symbol of the US-led global security order is increasingly under threat by the Yemeni rebel group”, Jan 25, 2024, John P. Ruehl, Asia Times, Originally published at Globetrotter, at < https://asiatimes.com/2024/01/

6). “Geopolitical Risk in the Red Sea”, Jan 12, 2024, Silvia Boltuc, SpecialEurasia, Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598,fvv Volume 38 Issue 7, at < https://www.specialeurasia.

7). The Baltimore bridge collapse is only the latest — and least — of global shipping’s problems: From drought in the Panama Canal to the Houthis in the Suez to pirates off Somalia, we’re all paying the price”, Mar 27, 2024, Caroline Houck, Vox, at < https://www.vox.com/2024/3/27/

8). “Red Sea Crisis shakes up global maritime security landscape”, Feb 4, 2024, Wang Xu, China Military Online, at < http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/

This is a collection of 8 articles, that I selected from the plethora of material that is on the web concerning these issues. I tried to pick some from the left, some from the right, and even number 8, a press release from a person associated with the Chinese Military itself.

~~ recommended by dmorista ~~

Introduction by dmorista: The U.S. has been left behind by a number of Asian Societies when it comes to issues like levels of general industrial production, high-technology production, research and development, educational levels, personal income, home ownership, life expectancy, maternal and infant mortality, and even average stature. One of many other areas where the U.S. is still a key power is in the management and administration of maritime shipping, and in using its naval power to keep the SeaLanes open; promoting the right of ships to what they term as "Free Navigation" through international waters. China, South Korea, and Japan have larger and busier ports, they are also the three leading ship-building economies. But the U.S. still dominates when it comes to coordinating shipping and protecting the sealanes.

The U.S. has been a Maritime Power during its century of Hegemonic Power. Like the British Empire before it the U.S. ruling class has concentrated on its trade relations and business with Europe and many parts of what we now call the Global South. Its fleets have sailed the world's oceans but the U.S. has, in general, avoided getting deeply involved in the political affairs or military campaigns in the interior of the Great land mass of Eurasia, or of Africa for that matter. The current adversaries of the U.S. namely China, Russia, and Iran are all located in interior Eurasia where U.S. influence and activities were at a strict minimum over the years.

Various Geostrategic thinkers in the U.S. and in the U.K. have expounded on these ideas beginning with Alfred Thayer Mahan an American Admiral and Halford MacKinder a British Geographer. The ideas were further developed and adapted to the needs of the U.S. ruling class by Nicholas Spykman and even by Zbigniew Brzezinski. The U.S. not only maintained hundreds of military bases and kept fleets sailing around the Eastern and Western ends of Eurasia, but also provided various types of assistance to capitalist societies located around the deep interior states of the Soviet Union / Russia and China. In the 1960s and 1970s American techology was provided free to Japan, Taiwan, S. Korea, Singapore, and Hong Kong to give them solid business and scientific power to surround and isolate China. This was done despite a heavy cost associated with the economic decline of major American regions and industries. The American version is shown in Figure 1). below:

Now China has grown powerful and the West has weakened to the point that merely functioning as a low-wage export platform selling products to the West is no longer enough to provide the level of business investment and sales that Chinese corporations need to prosper. The Economic Collapse and Financial Crisis of 2007 – 2009 convinced Chinese Political and Economic planners that other means of promoting Chinese business had to be created. The Belt and Road Initiative, along with measures to increase demand for Chinese products by the population of China itself, were the responses. The Belt and Road System, that added terrestrial infrastructural projects to the ongoing maritime trade system is serving to tie together Eurasia and to a lesser degree Africa. Some of the projects are providing a transportation and pipeline system that connects formerly isolated regions of Eurasia with the road and rail networks of China and Europe. Some projects are pretty clearly just resource-extraction operations that are indistinguishable from the sorts of infrastructure built by the colonial powers in the past couple of centuries. A couple of maps depict the elements of this initiative, Maps 2 & 3 below:

Still through all the increase in infrastructure built in Eurasia and other areas the Chinese are just as dependent on Maritime Shipping Traffic to move products for sale from China to other regions. The Chinese build the largest share of cargo ships now, with around 48% of the world's shipbuilding capacity in China, 25% in S. Korea, and 15% in Japan (the actual figures vary depending on how it is measured numbers of vessels or gross tonnage etc.). {See, “BIMCO: Chinese Shipyards Achieve Market Share Record in 2022”, Feb 16, 2023, Anon, The Maritime Executive, at < https://maritime-executive.

But what has developed is a system of massive Global Shipping in which finished products many of which are made in China, using raw materials shipped to China from mines and plantations around the word, are moving in ships generally built in China, S. Korea, and Japan; but over which the Chinese exert precious little control. The Wealthy elements of The West still control most of the legal, insurance, and administrative aspects of this trade. It moves through long-established routes and transits through just 2 major globally important canals and other chokepoints. A ship's captain of local pilot, like in the Ever Given from Evergreen Marine in 2021, can make a mistake or exercise poor judgement and much of the system can get gummed up for anything from days to weeks. Disgruntled and ignored political / para-military formations, like The Houthis, can now challenge ship movement and cause major disruptions driving up insurance and shipping charges and slowing down ship movements around much of the planet. A port, like Baltimore, where shoddy and inadequate protection structures and lack of the assistance of a couple of tugboats can cause infrastructural debacles that will take 5 years and several billion dollars to remedy.

China's largest market for its industrial products is Europe. 60% of those products pass through the Suez Canal in container ships. Western based geo-strategic and military analysts all claim that Iran is supplying the Houthis with the weaponry needed to disrupt the trade route that passes through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal. There is no doubt that the Chinese have far closer relations with the Iranians than any entity from the West does, but just as with U.S. proxies in places like Ukraine and parts of Latin America the dominant power does not exercise complete control over the local forces. We are also seeing the shadow of the 1953 Coup that deposed Mossadegh and imposed the Shah on Iran for 26 years. The current Iranian political situation would, no doubt, be very different had the 1953 Coup never taken place. The Chinese and Western leaderships might need to coooperate on resolving the situation in Yemen and see to it that the people there are treated fairly.

The most basic questions we need to be asking and demanding that they are addressed are these:

Why aren't considerations such as the real cost of manufacturing products and the actual assistance impacts to the physical and social environment dealt with seriously. What must be done to make sure that those sorts of issues are actually taken seriously. Capitalists are very good at assessing costs and deciding what is the cheapest place and manner to run these kinds of operations. But many of the actual costs are ignored or are considered to be “Economic Externalities”. If there is local resistance to opening a new mine or highway or canal system the local government will, with some assistance from the major Capitalist Corporations and the rich in their home society, suppress dissent. This has often been accomplished by murdering and/or imprisoning the dissidents. We are far too powerful, as a species, on this planet to keep operating this way.

Comprehensive measures to see to it that modern technological devices are all built in such a way that their components are easily and much more safely recycled than is the case now would be a big start. These are big problems and their resolution seems out of reach now, but we must start to apply political pressure with grass-roots propaganda campaigns. Yes propaganda can be a positive force!!

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Monthly Review | April 2024 (Volume 75, Number 11)

On December 14, 2023, the Wall Street Journal published an interview with premier U.S. imperial grand strategist Richard Haass titled “A World in Disarray?” From 1989 to 1993, Haass was special assistant to President George H. W. Bush and senior director for Near East and South Asian Affairs on the staff of the National Security Council. While in these positions, he played a central role in developing the strategy for the U.S.-led 1990 Gulf War against Iraq. From 2001 to 2003, he served as director of policy planning for the Department of State under President George W. Bush. In this capacity, he was the principal adviser to Secretary of State Colin Powell, helping to coordinate regime change during the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. For two decades, from 2003 to 2023, Haass was president of the Council on Foreign Relations (commonly known as “the imperial brain trust”). Today, he is a senior counselor for the investment bank Centerview Partners, advising on geopolitical matters. Recently, he headed up a group of top U.S. foreign policy figures, all drawn from the Council on Foreign Relations, engaged in “secret talks” with Russia on the Ukraine War (Richard Haass interview, “A World in Disarray?: A Longtime Diplomat Says It’s Worse than That,” Wall Street Journal, December 14, 2023; Josh Lederman, “Former U.S. Officials Have Held Secret Talks with Prominent Russians,” NBC News, July 6, 2023; Laurence H. Shoup and William Minter, The Imperial Brain Trust [New York: Monthly Review Press, 1977]).

In its December 2023 interview, the Wall Street Journal asked Haass about his 2017 book, A World in Disarray. In his judgment, were things better or worse, six years later? He answered that today it is “Disarray on Stilts. When the [2017] book came out, I was criticized for being too negative. In retrospect, I wasn’t negative enough.” Not only has the “new world order” pronounced by Washington after the 1990 Gulf War and the demise of the Soviet Union turned into a “new world disorder” as “the relative position” of the United States has “deteriorated,” this disorder is now turning into a state of chaos. This is partly due to the rise of other powers, but also derives from the neglect of “the U.S. defense manufacturing base,” which means that the United States is no longer capable of fighting major proxy wars effectively. For Haass, “the rise of China, which is not a status quo power, represents a shift in the balance” on the world stage, while “a truly disaffected Russia” now has the ability to act, “as we’re seeing in the Ukraine and elsewhere.” This represents a transformation in power relations, taking various forms and “moving around the world.” Ukraine, Haass declared, will not be able to regain its lost territory, and it should concentrate on maintaining its mere existence, taking advantage of the fact that it is now “integrated one way or another into the EU and NATO.” The strategy at present, we are told, is to await the anticipated weakening of the Kremlin following Putin’s eventual departure. The United States/NATO could then presumably exercise leverage against Moscow as a “pariah” state, thereby bringing about all-out regime change (Haass, “A World in Disarray?”; Richard Haass, A World in Disarray [London: Penguin, 2017], 11).

Israel’s full-scale assault on Gaza, Haass explained to the Wall Street Journal, is a major foreign policy disaster for the United States, but one in which Washington simply has no choice but to back “Netanyahu and his colleagues” at all costs, supporting Israel’s “one-state nonsolution” with its no-holds-barred war on Hamas and the continued movement of settlers into the West Bank. “They [the Israeli forces] are causing an awful lot of civilian casualties and deaths in the process,” Haass acknowledged, while indicating that this “is a separate conversation,” one with which he has no intention of engaging. After Hamas is “degraded”—it cannot, he said, be destroyed—Gaza will have to be ruled by Israel directly with continued U.S. backing. There is no viable regime change strategy, no real endgame, only the sheer exercise of force, viewed as necessary to maintain Israel as a “democratic Jewish state.” On the Chinese front, the United States, Haass insisted, must declare that it is willing, ready, able, and committed to go to war with China over Taiwan (Haass, “A World in Disarray?”; Richard Haass, “What Friends Owe Friends,” Foreign Affairs, October 15, 2023).

A historical perspective on Haass’s views can be obtained by going back to 2000, when he delivered an important speech titled “Imperial America,” presented at the Atlanta Conference in Puerto Rico on November 11, 2000, shortly before he joined the George W. Bush administration. Here, he envisioned a strategy modeled after British hegemony in the nineteenth century. Ten years after George H. W. Bush first spoke of a “new world order” and nine years after the demise of the Soviet Union, Washington’s hopes of creating a unipolar world under U.S. “primacy,” Haass warned, were rapidly receding in the face of a much stronger China and the re-emergence of Russia as a great power. However, a resurgence of U.S. “imperial power” was still possible, he argued, through the continued enlargement of NATO further to the east toward Russia (with the objective of eventually bringing Ukraine into NATO); a renewed U.S. commitment to so-called humanitarian military interventions across the globe; the bolstering of U.S. hegemony over “free trade” institutions; and the global expansion of U.S. missile defense systems (part of the Pentagon’s overall nuclear counterforce strategy). In The Reluctant Sheriff, published a few years before his “Imperial America” speech, he had argued that U.S. military interventions should be based on unilateral decisions by the United States, as the world’s “sheriff,” but backed up each time by a “posse” that submitted to its orders, forming a “coalition of the willing,” thus giving a sense of support by the international community. Haass ended his “Imperial America” speech with a reference to “Imperialism Begins at Home,” calling for national unity as the basis of U.S. empire (Richard Haass, “Imperial America,” Atlanta Conference, Puerto Rico, November 11, 2000, Brookings Institution; Richard Haass, The Reluctant Sheriff [New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 1997]), 93; John Bellamy Foster, Naked Imperialism [New York: Monthly Review Press, 2006], 97–106, 115–16).

Yet, only a decade and a half after Haass first proposed his “Imperial America” strategy, he was forced to recognize that the U.S. unipolar world that he had dreamed of was no longer possible. This could be traced primarily to the abandonment of any sense of national unity on the domestic front (that is, adherence to the “Imperialism Begins at Home” principle). This was particularly evident during the 2016 election campaign of Donald Trump, with the rise of what Haass referred to as “class” conflict foreign to the “common American identity,” leading to a tendency to “continued paralysis and dysfunction at best and widespread political violence and dissolution at worst” and extending to all parts of the body politic. Ironically, it was the class struggle endemic to capitalism, in Haass’s own account, that finally put an end to his (and Washington’s) grand design for an “Imperial America.” The fallback strategy today, he informs us, is a defense of the hegemonic “rules-based international order” made in Washington. “Medium powers in Europe and Asia, as well as Canada,” we are told, cannot hold the world together since they “would simply lack the military capacity and the domestic political will to get very far.” The “rules-based international order” thus can only be fashioned and kept in place by the United States of America, viewed as the indispensable imperial power (Richard Haass interviewed by Thomas B. Edsall, “Trump Has Ushered in the Age of ‘Great Misalignment,'” New York Times, January 10, 2024; Richard Haass, The World: A Brief Introduction [London: Penguin, 2020], 302–3; Haass, A World in Disarray, 8–15).

China is winning the battle for the Red Sea

Nathan Levine

February 11, 2024 5 mins

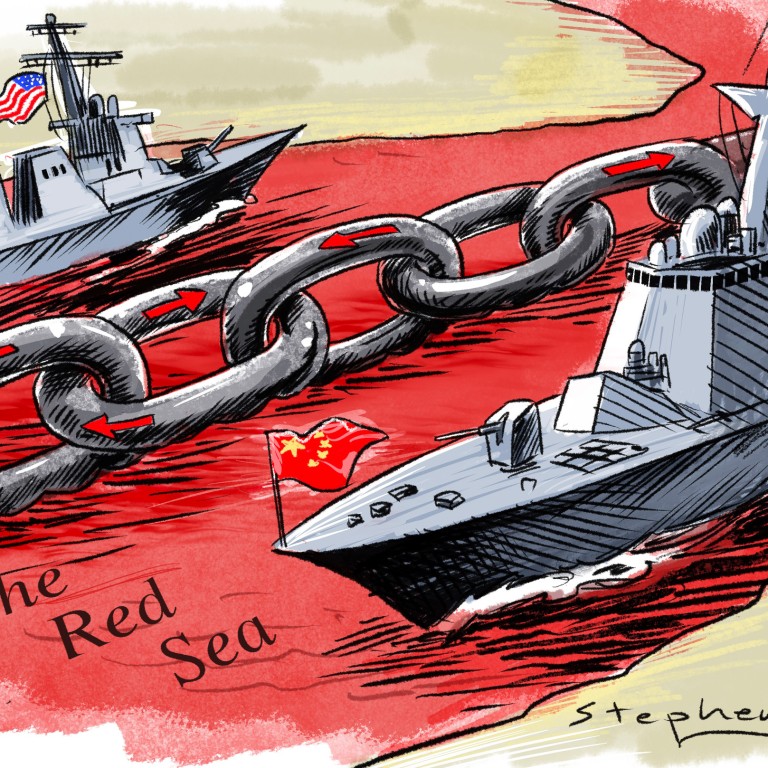

Hardly for the first time, remote Arab tribesmen are reshaping the world. Piratical attacks on international shipping by Yemen-based Houthi rebels have created a significant security crisis in the Red Sea. The world’s largest shipping lines have been forced to suspend transit through the Red Sea and thus the Suez Canal. And with nearly a third of global container traffic typically flowing through Suez, this has seriously disrupted world trade. Yet the most enduring impact of the crisis may be on the geopolitical balance between two great powers, each many thousands of kilometres away from the scorching sands of the Arabian Peninsula: China and the United States.

As the world’s largest trading nation, China has much at stake in the Red Sea. Europe is China’s top trade partner, and more than 60% of that trade by value usually flows through the Suez Canal. With that route disrupted, cargo vessels are diverting around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, adding up to two weeks in additional travel time and vastly increasing shipping costs. By 25 January, the average cost of shipping a 40-foot container from Shanghai to Genoa spiked to $6,365, an increase of 464% from two months earlier. Insurance rates have also skyrocketed. What’s more, Chinese companies have in recent years poured billions of dollars’ worth of investment into assets in the region, such as the 20% stake in the East Port Said container terminal of the Suez Canal that is now owned by Chinese state shipping giant COSCO. At a time when China’s growth rate is already struggling, the crisis risks imposing a serious further drag on its economy.

Apparently perceiving this vulnerability, Washington has tried to use it as leverage to convince Beijing to help end the crisis. China is the top economic and geopolitical backer of Iran, which in turn backs the Houthis, using them as a proxy to needle Israel, the United States and its allies. Some officials in Washington are convinced that, if it really wanted to, Beijing could quickly pressure Tehran into ending the Houthi attacks. Biden administration officials have “repeatedly raised the matter with top Chinese officials in the past three months”, according to the Financial Times, and US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan recently flew to Thailand to directly plead the administration’s case in a meeting with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi.

This diplomatic effort seems to have failed. Aside from a tepid public statement calling on “all relevant parties” to “ensure the safety of navigation in the Red Sea”, Beijing appears to have made no move whatsoever to remedy the situation. Instead, it called on Washington to “avoid adding fuel to the fire” in the Middle East. The attacks continue.

Some in Washington are pouting. Rep. Jake Auchincloss (D-Massachusetts), for instance, slammed China in a Congressional hearing in late January for being “not only missing in action as a purported upholder of international commerce and rules, but… in fact actively undermining the potential for a peaceful resolution to this issue”. This failure to intervene was just “another example of the malign and malicious attempts at global leadership from the Chinese Communist Party”.

But Auchincloss and others of like mind in Washington should perhaps be careful what they wish for. For decades — indeed, arguably for the better part of two centuries — it has been the United States that has served as the world’s “upholder of international commerce and rules”. In fact, it was a determination to protect the flow of maritime commerce from pirates that induced the young United States into its first foreign intervention, the Barbary Wars of 1801 and 1815, and permanently forged its identity as an international actor. If the nation were truly to become and remain a merchant republic that meant that it must, as then-President Thomas Jefferson declared, “superintend the safety of our commerce” through “the resources of our own strength and bravery in every sea”.

Two centuries later, the US Navy was still operating under the slogan of “A Global Force for Good”. Which is to say that the whole image — and reality — of America as a superpower largely rests, like the British Empire before it, on its ability to secure global trade. If there is any remaining shred of the “Pax Americana” on which the whole recent era of globalisation was built, this is it.

It is in this context that Washington officials ought to consider what it would mean if Beijing were to listen to their pleas and actually take over America’s role as a security provider. If the nations of the world were to begin turning to China for “global leadership” rather than the United States whenever their merchant ships were in need of protection, it would decisively mark the transition from an American century to a Chinese one, much as Britain once yielded the seas to its former colony. Washington should count itself lucky that Beijing has so far declined to try out for the role.

Meanwhile, America’s own effort to perform its old job of securing the sea lanes has proved little more than a fiasco. With the US Navy severely undermanned and overstretched around the globe, it attempted to assemble “Operation Prosperity Guardian”, a multinational coalition of forces under its command meant to patrol the Rea Sea. But this effort functionally collapsed almost immediately when France, Italy and Spain — all of whom Washington prematurely announced would be members — declined to participate, saying they wouldn’t accept US command. No Middle Eastern countries other than Bahrain signed up either. In a throwback to yesteryear, navies are instead each going solo and escorting the vessels sailing under their own flags and titles. What we are seeing, then, is a true breakdown in the “international order” — in the sense of there being any order — that was once imposed by American power. We are returning to an older, more typical world in which there is no world policeman, and everyone is obliged to protect their own national interests.

The Chinese are well prepared to capitalise on this situation. Although COSCO has for now also abandoned the Red Sea route, other smaller Chinese shippers have spotted commercial opportunity and leapt to fill the gap. China United Lines (CULines), for example, has rushed to start up a “Red Sea Express” service linking Saudi Arabia’s Jeddah to Chinese ports. They are able to do so because the Houthis seem to be under strict orders to try to avoid attacking China-linked vessels. Ships still running the straits into the Red Sea now regularly make sure to prominently display Chinese flags and use their satellite identification data to announce that they have Chinese owners, or even just Chinese crew members. The number of vessels transiting the area while preemptively broadcasting that they carry Chinese crew has surged from less than two per day to more than 30 in late January. Apparently this is the magic talisman to keep pirates at bay — though China’s navy has at least three warships in the area to escort its vessels, should it prove insufficient.

The reason Beijing seems so relaxed about the crisis is obvious: this is a situation in which China wins either way. Either the threat continues but shipping is safer for Chinese vessels than for others, in which case sailing under the protection of the red and gold flag may become a coveted competitive advantage, or Beijing finally tells Iran to knock it off, in which case China becomes the principal beneficiary of the security vacuum left by the United States. Both outcomes would be geopolitical coups. No wonder China is willing to accept a little short-term economic pain as the situation plays out.

Meanwhile, the crisis also provides China with a real justification for continuing to rapidly build out a “blue water” navy able to project power far from its own shores. As it happens, this is the same justification traditionally been offered by the United States: that, in the absence of security and stability, it needs the ability to protect global sea lanes and the lives of its citizens abroad. The military base China built in Djibouti in 2016 to enable the deployment of its warships across the Indian Ocean and around the Horn of Africa now looks prudent.

This is how the “world order” has always been shaped and reshaped: by nations and empires acting abroad to protect their own interests — or progressively failing to do so while others move to fill the void. The crisis in the Red Sea is therefore both symbolically and practically meaningful. Unless the United States and its allies can get their act together, we may look back on this as a moment when a vast geopolitical shift was revealed for all to see. As for everyone else, it’s likely that the crisis will serve as a sign that the time to prepare for the harsh realities of a far more “multipolar”, less globalised world has by now well and truly arrived.

Nathan Levine is a Visiting Fellow in the B. Kenneth Simon Center at the Heritage Foundation and a non-resident Research Fellow with the Asia Society Policy Institute.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

The Red Sea Crisis Proves China Was Ahead of the Curve

The Belt and Road Initiative wasn’t a sinister plot. It was a blueprint for what every nation needs in an age of uncertainty and disruption.

Foreign Policy, January 20, 2024, 5:46 AM

By Parag Khanna, the founder and CEO of Climate Alpha.

(Caption: An aerial view shows stranded ships dotting bright blue water as they wait to cross the narrow Suez Canal seen in the distance at its southern entrance in the Red Sea.)

An aerial view shows stranded ships waiting to cross the Suez Canal at its southern entrance near the Red Sea port city of Suez, Egypt, on March 27, 2021. Mahmoud Khaled/AFP via Getty Images

Over the past two months, a sudden surge in Houthi rebel attacks in the strategic Bab el-Mandeb Strait connecting the Red Sea to the Arabian Sea prompted the world’s largest shipping carriers to halt transit through the Suez Canal for several weeks—with even more rerouting their vessels as the United States and Britain launched strikes on Yemen and the situation has escalated.

As ships loiter in the Mediterranean or Arabian weighing their options, others are busily bypassing the strait entirely. In mid-December, Saudi Arabia quickly gave its blessing to forming a “land bridge” from the Arabian to the Mediterranean by which goods docking in Persian Gulf ports such as Jebel Ali in the United Arab Emirates or Mina Salman in Bahrain could transit its territory via truck to Israel’s Haifa Port.

You read that correctly. Hamas’s horrific Oct. 7 attack on Israel not only failed to scupper the Abraham Accords, but despite Saudi Arabia and the UAE strongly supporting a two-state solution to the conflict, both are accelerating their infrastructure cooperation with Israel in order to cope with maritime disruptions—and of course to collect transit fees that would normally flow into Egypt’s coffers. Even better for boosters of overland transport, the Gulf-Israel corridor shaves ten days off the Red Sea maritime route.

Geopolitical shocks from Red Sea maritime terrorism and the Russia-Ukraine war have driven up logistics costs and food prices just as the world economy—and particularly developing countries—is struggling to recover from the fiscal pain of the COVID-19 pandemic. (And another volcano in Iceland erupted recently, driving up air freight costs, too.)

The solution to today’s perpetual volatility won’t emerge from episodic summits between Beijing and Washington or G-7 group therapy sessions or from talkfests such as the World Economic Forum or U.N. climate conferences. Instead, there is precisely one pathway for a world plagued by dire mistrust and unpredictable crises to take meaningful collective action in the global public interest—and that is to build more pathways for supply to meet demand. The solution to supply shocks is more supply chains. More belts, more roads.

From the back of a large conference hall, the ceiling is seen with ornate light fixtures in the top half of the composition. In the lower half, a man with a suit stands at the podium in the center of a stage the width of the room. Flanked by two large screens at either side, both display a close-up of him from the waist up. As seen from far away, the man is shrunk to a tiny fraction of the image.

Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks during the opening ceremony of the third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on Oct. 18, 2023. Pedro Pardo/AFP via Getty Images

China is the one country that has known this—and acted on it—for years. When China convened leaders and representatives from more than 130 nations in Beijing last October to mark the 10th anniversary of the launch of its signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), it was frowned upon by many Western leaders—just as it was a decade ago—as a stealth plan to undermine the Western-led international order by placing China at the center of global trade networks.

From a functional perspective, however, the BRI represents what all countries should do in their own national interest: build as many pathways as possible for supply to meet demand, both as a hedge against unforeseen disruptions but also to boost one’s connectivity and influence.

The need for such hedging became all too clear in 2021, when the massive container vessel Ever Given ran aground in the Suez Canal, all but freezing trade between Europe and Asia just as the world was seeking to revive trade amid the COVID-19 downturn. While the brunt of the backlog was cleared within two weeks, it was a jittery experience for the world’s just-in-time supply chains, by which manufacturers and retailers hold low inventory of components and goods on the assumption of frictionless trade. It also carried a hefty weekly price tag in insurance premiums for delayed shipments.

Whether the vulnerability of maritime chokepoints is exposed by Houthi terrorism in the Red Sea, Russia’s grain blockade on the Black Sea, drought in the Panama Canal, or a potential South China Sea conflict near the Strait of Malacca, there is no reason why the largest zones of the world economy—North America, Europe, and Asia—should be held hostage to such sporadic and uncontrollable events.

Sure, ships could opt for the pre-Suez Canal route rounding Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, adding 10-14 days to a normal 20-30-day shipping time. But instead, the wiser path was taken by China and Europe (which are each other’s largest trading partners): Trans-Eurasian rail cargo doubled to 1,000 freight trains per month in early 2021, offering greater reliability and punctuality.

More highways and railways across Eurasia, and ports along the Indian and Arctic oceans, are essential to creating flexibility and alternative routes for the global freight and commodities trade on which the proper functioning of the world economy depends. Such investments are effectively preemptive measures against the inflationary shocks that result from protectionism, geopolitics, and climate change.

Opinion | As Red Sea shipping attacks continue, pressure grows for China to act

- Despite the Houthis’ promise of safe passage, Chinese vessels remain at risk of being wrongly targeted

- The crisis presents an opportunity for China to take more decisive action, including jointly with the US, in spite of the geopolitical challenges

It underscored the group’s inability to precisely identify its targets, and suggests it may be a matter of time before Chinese vessels come under attack. China’s approach to the situation reveals its challenges, both economic and geopolitical.

With ships avoiding the Red Sea, the volume of trade going through the Suez Canal had fallen by 42 per cent over the past two months, said Unctad on January 26. China is primarily concerned about the increased time and costs associated with shipping through alternative routes. The freight rate for the Shanghai-Northern Europe route has surged, from US$581 per 20-foot equivalent unit (TEU) in mid-October to US$2,694 at the end of December – triple what it was at the start of December – surpassing US$3,000 in January.

Beyond economic costs, however, China also has to consider the Red Sea situation against its broader role in global affairs.

03:21

US-led coalition strikes Iran-backed Houthi fighters in Yemen

Analysts have pointed to the delicate situation: it is too crucial to overlook but too sensitive to explicitly mention. Taking decisive action in response presents challenges for China, particularly when it comes to pressuring Iran.

Importantly, China sees the Red Sea tensions as a spillover from the Gaza conflict. Its concern is with protecting its interests against a broader regional conflict strategy. And there are concerns in the region that additional measures taken by China, such as deploying its warships, might be seen as a threat to regional security.

The Red Sea region is significant to the strategic interests of both the US and China; they want to see stable trade, energy and resource flows, counterterrorism efforts and the promotion of good governance and stability. But US-China tensions in recent years have reduced the opportunities for both countries to cooperate in the Red Sea.

This crisis is an opportunity for a breakthrough. Despite US military action, commercial shipping in the Red Sea remains under pressure. China should consider contributing more proactively, drawing on its experience in escorting commercial vessels during previous escalations in piracy in the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea.

The potential for US-China coordination arises not out of affection but the critical importance of issues such as supply chains and energy supply to both Beijing and Washington. Negotiations would be crucial to establish frameworks and mechanisms, and to plan for how the respective US and Chinese militaries should respond when they come into contact in the local area.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

How Houthis threaten US control over global shipping - Asia Times

On December 30, the Singapore-flagged Maersk Hangzhou, owned by Danish company Maersk Line, came under missile and subsequent boat attacks by Houthi rebels in the Red Sea. The US Navy responded by using helicopters to destroy three of the four ships used in the assault.

Maersk, the world’s largest shipping company, immediately announced it was suspending operations in the Red Sea indefinitely, rejoining major Western shipping firms and energy companies in redirecting shipping away from the region.

Houthi attacks have occurred regularly since October after the group declared it would target ships associated with Israel. In response, Washington announced a task force on December 18, Operation Prosperity Guardian, to combat the attacks, and imposed sanctions on Houthi funding networks, mainly linked to Iran.

But the difficulty in securing the Red Sea’s narrow waters and the bottleneck at the Suez Canal have laid bare the fragility of global shipping, with an estimated 20% decline in ship traffic through the Red Sea in December. Daily container-vessel traffic through the Suez Canal had meanwhile halved by early January compared with a year before.

The repercussions of redirecting shipping are being felt globally, with ocean cargo rates skyrocketing since the attacks began. By early January, the logistics company Freightos reported that rates for Asia-to-Northern-Europe shipping had more than doubled to above US$4,000 per 40-foot container.

By mid-January, the cost of sending a 24-foot shipping container from India to Europe and the US east coast had risen from $600 to $1,500. Adding to the financial burden, surcharges ranging from $500 to $2,700 per container are anticipated, and rates for shipments from Asia to North America have also experienced significant increases.

For those daring to navigate the Red Sea, insurance premiums have more than tripled from 0.2% to 0.7% of a vessel’s value per journey. Though consumers haven’t yet felt the brunt of rising prices, the specter of inflation looms in the coming weeks.

Global stability imperiled

The anticipated domino effects recall the aftermath of the 2021 Ever Given disaster, when a ship ran aground in the Suez Canal for six days, leaving a lasting impact that reverberated for months.

The imperative for the US in controlling and stabilizing threats to shipping is underscored by its commitment to global economic stability, dollar-dominated international trade, and the leverage it gains over allies and adversaries.

Being able to ensure or compromise the safe movement of other countries’ goods and military vessels complements Washington’s ability to enforce blockades and economic sanctions, as well as to respond quickly to global crises and combat terrorism and organized crime.

Despite the challenges in maintaining its influence, the US has successfully dealt with threats to global shipping before. Multilateral safeguards like the Combined Maritime Forces, consisting of dozens of countries under US command, monitor the Middle East, and measures such as the Combined Task Force 151 (CTF-151), created in 2009, have successfully tackled specific threats such as Somali piracy.

Success of Houthis’ strategy

Since 2015, the Houthis have intermittently targeted ships in the Red Sea, but their sustained campaign since October has raised significant doubts about the US military’s capacity to safeguard shipping.

Operating out of Yemen, the Houthis employ a mix of missiles, radars, helicopters, small boats, and inexpensive drones, presenting a challenge as they lack substantial infrastructure susceptible to targeting. The use by the US Navy of $2 million missiles to intercept $2,000 drones adds to concerns about the cost-effectiveness of its response.

Benefiting from Iranian logistical aid and driven by their steadfast commitment to the Palestinian cause, the Houthis have encountered minimal resistance from regional countries hesitant to escalate tensions.

After its eight-year campaign in Yemen, neighboring Saudi Arabia withdrew from the country and entered peace talks with the Houthis in 2022. Apart from tiny Bahrain, local partners of the US have refrained from joining Operation Prosperity Guardian out of fear of being accused of supporting Israel.

Even Egypt, which is witnessing substantial losses in transit revenue through the Suez Canal, has opted to stay on the sidelines.

The inability of the Saudi military, bolstered by modern Western weapons, to overcome Houthi forces over the past decade by relying on air raids and drone strikes implies that a ground intervention may be necessary to defeat the Houthis effectively. Yet Washington lacks the resolve and influence to undertake such an effort.

Shaky support

Notably, NATO allies, including France, Italy and Spain, withdrew from Operation Prosperity Guardian to avoid being under US command, leaving only a few core allies such as the UK and Australia, the latter of which has sent 11 military personnel to the region but no ships.

Meanwhile, other major powers have sought to conduct their own independent operations in the region. After declining Washington’s invitation to join Operation Prosperity Guardian, the Indian Navy began its own operations in the region. China also declined the opportunity to join the multilateral coalition, and has also distanced itself from US messaging on the crisis as it deploys its own military vessels to the region.

Failing to deter the Houthis will inspire others to test Washington’s willingness to defend open shipping lanes. After declining significantly in recent years, Somali piracy increased in 2023. Southeast Asia has also seen a steady rise in piracy over the last few years, and there are fears incidents could continue to rise with the US distracted in the Middle East.

Additionally, Iran has seized Western ships sailing through the region before and was accused by the Pentagon in December of using a drone to attack a chemical tanker in the Indian Ocean.

Political ramifications

The attacks and blowback from the conflict have reverberations beyond regional trade. In December, Malaysia closed its ports to Israeli ships, while Russian actions in the Black Sea have further disrupted international shipping.

Moreover, the situation could impact “freedom of navigation” exercises globally. Heightening tensions and China’s escalatory movements in the South China Sea and Taiwan have stirred unease in the US, prompting two-day talks between defense officials from Washington and Beijing in early January ahead of Taiwan’s recent election.

Russia, China and Iran welcome the United States’ struggle to maintain control over sea lanes due to the Houthi threat, seeing it as an opportunity to exploit Washington’s global standing. However, particularly in the case of China, they have also benefited from the stability that this system has provided to global trade, and viable alternative routes for overseas trade remain undeveloped and untested.

Amid the chaos, the Panama Canal, another crucial juncture for international shipping, faces disruptions from severe drought lowering water levels. As only a limited number of ships can navigate through, Washington’s oversight in ensuring the uninterrupted flow of global sea lanes appears more precarious than it has been in decades.

While options like continued military convoys and the rise of private maritime security companies are on the table, the Suez Canal’s eight-year closure after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War remains an ominous reminder of what is at stake.

As Washington attempts to balance control with the risk of escalation, the Houthis have underscored the resilient influence of non-state actors in 21st-century geopolitics amid the resurgence of great-power competition.

The situation has become the latest litmus test for Washington’s commitment to preserving access to global sea lanes, even as it pivots toward friendshoring and reshoring economic policies encouraging overland trade and manufacturing in North America.

As the 2024 election season unfolds in the US and the impact of former president Donald Trump’s “America First” policies persists, safeguarding global sea lanes may emerge as a pivotal topic during the campaign. Coupled with the unique challenges posed by the Houthis, mounting an effective and decisive response against the maritime threat has so far proved elusive for President Joe Biden’s administration.

Ongoing US and UK air strikes against the Houthis have not prevented further attacks on shipping. The longer it takes to respond effectively, the greater the threat to the future of the current state of global supply chains and US dominance of the world’s waterways.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Geopolitical Risk in the Red Sea - SpecialEurasia

Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 38 Issue 7

Author: Silvia Boltuc

The US and British militaries conducted a significant retaliatory strike against Houthi forces in Yemen, targeting over 60 sites. President Biden emphasised that these strikes were in response to Houthi attacks on international maritime vessels, posing threats to personnel, civilian mariners, and trade and increasing the regional geopolitical risk.

The coordinated assault to degrade Houthi military capabilities and safeguarding the Red Sea involved multiple nations, albeit notably absent of participation from neighbouring countries in the Red Sea region.

The absence of key Arab nations, including Egypt, UAE and Saudi Arabia, poses challenges to the effectiveness of the coalition, while Saudi Arabia’s strategic considerations, rooted in diplomatic overtures towards the Houthis and Iran, explain its non-participation.

The criticality of Red Sea maritime routes, also for China’s trade, and Russia’s growing relations with Arab nations, underscores the broader geopolitical implications and risks associated with the US-British bombings.

Key Findings

- The counterattack on Houthi forces in Yemen has the potential to escalate the existing conflict between Israel and Hamas to a wider scale, potentially spreading to the broader Middle East.

- The ‘Red Sea coalition’ lacks participation from neighbouring Arab countries, with only Bahrain joining the effort.

- Saudi Arabia, despite significant Red Sea reliance, refrained from participating, showcasing a strategic focus on diplomatic solutions and regional stability.

- China’s significant reliance on Red Sea maritime lanes, where 60% of its exports to Europe traverse, highlights its vested interest in ensuring uninterrupted shipping routes.

- Oil prices rose more than 2.5% as the United States and Britain carried out air and sea strikes on Houthi military targets in Yemen.

Background Information

On October 19th, 2023, Yemen’s Houthi movement initiated a series of attacks, targeting the ships in the Red Sea linked to Israel. The Yemeni rebels asserted unwavering support for the Palestinian cause.

The United States assembled a multinational naval coalition to help safeguard commercial traffic from attacks by Yemen’s Houthi movement, known as Operation Prosperity Guardian.

The hesitancy of numerous nations, including certain NATO members, to join the coalition, raises concerns about the effectiveness of it. The root cause of this lack of confidence lies in the understanding that achieving a ceasefire in Gaza would be sufficient to halt the crisis in the Red Sea, a feat within the capabilities of the United States. However, Washington’s ongoing support for Israel’s bombing of Gaza has led to a division in Western support.

Analysis

The absence of key regional players in the coalition underscores the complexity of Red Sea geopolitics. Saudi Arabia’s non-participation reflects a nuanced approach, balancing security concerns with a desire for regional peace and stability.

The Houthis have been engaged in a prolonged conflict with the Saudi Arabia-backed Yemeni government. Recent positive diplomatic engagements between Riyadh and the Houthis indicate a Saudi effort to seek regional stability, aligning with Vision 2030 goals, tourism initiatives, and preparations for hosting major events such as the FIFA Cup.

The Houthis have previously targeted cities in Saudi Arabia, and there is a risk of renewed attacks if Riyadh decides to join the coalition.

Moreover, Riyadh and Tehran recently normalised relations after years of tension, a development that could face obstacles if Saudi Arabia were to join the coalition conducting airstrikes in Yemen.

Arab nations are grappling with a challenging situation. Notably, Egypt, which holds control over the Suez Canal, has refrained from joining the international coalition. The Arab League consistently calls for a ceasefire in the Israeli conflict with Gaza, while Western nations predominantly express strong support for Israel.

In addition to the Western front and Arab players, China’s dependence on Red Sea shipping routes adds a layer of global significance to the conflict, influencing international decisions and complicating regional dynamics. 60% of China’s exports to Europe traverse the Red Sea. While it aligns with China’s interests to weaken US maritime capabilities, it is crucial for China and its investments that maritime routes operate efficiently.

Significantly, the UN Security Council resolution urging an immediate cessation of Houthi attacks on shipping in the Red Sea encountered abstentions from Russia and China. This highlights a nuanced approach by these superpowers, both of which have witnessed a considerable increase in relations with Arab countries in recent years.

Geopolitical Risk Assessment

The non-participation of key regional actors introduces risks of limited effectiveness in the coalition’s operations. The Saudi-Houthi diplomatic efforts, while positive, may face challenges, and China’s interests could be jeopardised if conflict escalation disrupts vital shipping lanes.

The bombing carried out by the United States and Britain, indeed, poses a risk of escalating the conflict in the Middle East, even though it is specifically targeted at certain locations within Yemen. Nevertheless, there is a concern that it could impede the ongoing efforts made in recent years to stabilise the country, which has been devastated by a prolonged civil war.

On January 12nd, 2024, after the strike, oil prices rose more than 2.5%. A sudden oil price shock has various economic consequences, including inflationary pressures, reduced consumer spending, a global economic slowdown, adverse impacts on energy-intensive industries, currency depreciation for oil-dependent nations, heightening geopolitical tensions. Persistent tensions in the Red Sea or a broader conflict in the Middle East would significantly impact oil markets, triggering a substantial geopolitical shock.

Last, the reputations of both Arab countries and the United States are on the line. They are confronted with escalating pressure from their populations to secure a ceasefire in Gaza. Launching attacks on the Houthis, who support Palestine, may have repercussions on internal support. Simultaneously, the perceived power of the United States in the Middle East has recently been doubted. The results of this operation will undoubtedly play a crucial role in shaping the future of U.S. involvement in the region.

Scenarios Analysis

- Regional Stability Scenario: Diplomatic/military efforts result in a de-escalation in the Red Sea, gradually paving the way for the restoration of regular transit.

- Limited Coalition Effectiveness Scenario: Without active regional participation, the coalition’s effectiveness remains constrained, and diplomatic complexities persist.

- Global Economic Impact Scenario: Escalation of conflict disrupts Red Sea shipping routes, impacting global trade and oil markets, triggering a substantial geopolitical shock.

Conclusion/Recommendations

The situation demands continued diplomatic engagement to address regional dynamics comprehensively. A balanced approach, considering geopolitical complexities, is crucial for achieving sustained stability in the region and safeguarding global economic interests.

The current prevalence and intensity of global conflicts should prompt international actors to reassess overly aggressive policies, as they pose a risk of uncontrollable consequences for global stability. The shift towards a multipolar world necessitates increased adherence to international law and a commitment to diplomatically resolving crisis events.

xxxxxxxxxxxxx

The Baltimore bridge collapse is only the latest — and least — of global shipping’s problems

From drought in the Panama Canal to the Houthis in the Suez to pirates off Somalia, we’re all paying the price.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/73235767/GettyImages_2115632217.0.jpg)

Baltimore woke up yesterday to horrific images of the Francis Scott Key Bridge collapsing into the harbor after the cargo ship Dali lost power and collided with a support column.

It’s a horrible tragedy — six construction workers who were on the bridge at the time are missing and presumed dead — and one that will likely take at least several billion dollars to repair.

In a small bright spot, the macroeconomic impact will likely be limited. (While Baltimore is the US’s 17th largest port and there will be some costs and delays, particularly around automobiles and coal, other ports will quickly handle rerouted container ships.)

There is a reason, however, that economic concerns immediately spiked: The global shipping industry is having a bit of a rough time right now.

International shipping traffic is being choked at two separate, vital points — the Panama Canal in the Western hemisphere and the Suez Canal in the Eastern — which combined account for more than half of the container shipping that links Asia and North America.

And as awful as this Baltimore incident was, it was, by all accounts, a rogue accident. The root causes of these other disruptions, though? They’re not quite as easily fixed.

Global shipping’s current problems, briefly explained

The Baltimore incident encapsulates one thing really well: just how globalized the shipping industry is. The Dali was a Singapore-flagged ship, with an all Indian-nationality crew, operated by the Danish company Maersk and on its way to Sri Lanka. (Thankfully, there were no injuries reported among the crew of the ship.)

This degree of interconnectedness — and how fragile it all is — probably feels familiar by now. Remember the wide swath of consumer goods that were subjected to back orders and shortages in 2021 as the global supply chain fell victim to a series of interconnected problems, including (but definitely not limited to) issues with container ships and ports?

This year is shaping up to be another difficult one for global shipping.

Low water levels in Panama — the result of a prolonged drought that began in early 2023 — forced canal officials late last year to cut the number of ships that pass through each day from the normal 38 to just 24. That’s left some ships stranded for more than two weeks, and others taking costly roundabout routes; major shipping companies are even switching some freight to railroad “land bridges” across parts of the country.

And in the Red Sea, the Houthis, a Yemen-based rebel group that controls much of the country’s north, have been waging an increasingly serious campaign of attacks against shipping, purportedly in protest of Israel’s war in Gaza. Ships are rerouting here, too, this time around the Horn of Africa, or facing the risk at added cost. At the start of this month, the Houthis sank a ship. And while the group is reportedly allowing safe passage to some ships — those affiliated with Russia and China — that’s not necessarily a foolproof guarantee.

Between the two, prices for freight containers from Asia to the US have doubled over the last six months.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25357078/GettyImages_1762119060.jpg)

Can’t we fix this?

It would be tempting to look at both of these issues and think, “Things will get better soon.”

And in some ways, they will. “The industry is going to find medium- to short-term solutions against these particular obstacles,” Nikos Nomikos, a professor of shipping finance and risk management at Bayes Business School in London, told me.

Take the Panama Canal problem: The cuts are, canal officials repeatedly say, a responsible adaptation to a particularly bad year. Droughts have happened before, and the weather phenomenon El Niño is exacerbating droughts throughout the Americas, with devastating consequences.

But this isn’t just a bad year. There are systemic issues at play with no quick answers. Climate change is worsening extreme weather events around the world, including droughts.

And that’s running up against another competing need. As Dulcidio De La Guardia, a director at the Morgan & Morgan Group in Panama, told the Latin American Advisor in February, “The lakes that provide water to the Canal are the same ones used to supply drinking water to the major cities of the country.”

“And water consumption has increased more rapidly than forecasted due to population growth, and poor management, waste, inefficiencies and corruption at the state-owned water company,” he said. There are potential solutions, but no easy or immediate ones.

And then in the Red Sea: While the Houthis might temporarily halt or reduce their attacks if a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas comes through, there’s no guarantee that they’ll stop altogether.

That’s because, as one Yemeni analyst told my colleague Josh Keating, the attacks serve a lot of the group’s other aims, allowing them to “disrupt economic activity, extract political concessions, and bolster their standing.” Having achieved that, they show no signs of backing down, even in the face of Western military strikes.

Moreover, this is part of a broader trend of increased geopolitical instability, all of which can impact — and increasingly is impacting — global shipping. See also: Russia blocking Ukrainian grain from transiting the Black Sea at times during that war, fears about how a war over Taiwan will affect the global economy, and more.

What’s happening in the Red Sea, in other words, is symptomatic of something fundamental.

The “principle of freedom of navigation is being challenged here,” Rahul Kapoor, the head of shipping analytics and research at S&P Global Commodity Insights, told Bloomberg in December about the Houthis’ attacks.

I’m not trying to be alarmist. Global shipping is a “resilient industry,” Nomikos told me.

But countries’ militaries and international shipping companies alike are thinking and planning for more maritime disruptions.

Customers, unfortunately, should too.

Any disruption’s net result “will be an increase in the freight cost, either because you have more fuel consumption and longer transit times, or because you require a premium to compensate you for the risks that you face,” Nomikos said.

Red Sea Crisis shakes up global maritime security landscape

- Source

- China Military Online

- Editor

- Huang Panyue

- Time

- 2024-02-04 17:54:02

By Wang Xu

Amidst global turmoil, chaos is spreading to the seas. Following the disruption of the Black Sea grain route due to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the Red Sea shipping lanes are now being affected by the spillover effects of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The Red Sea crisis sparks increasing global attention, highlighting major changes in the global maritime geopolitical landscape.

Countries in the Middle East have reacted lukewarmly to the US campaign “Operation Prosperity Guardian”. European countries have distanced themselves from the campaign because they are unwilling to hand over naval command. Italy, France, and Spain have made it clear that they will not follow the action against Yemen without authorization from the United Nations Security Council. Several merchant ships have used "China's interests are involved" as a reason to avoid maritime risks in the Red Sea, and many insurance companies have explicitly stated that “war risk insurance cannot be applied to US, UK, and Israeli vessels sailing towards the Red Sea.”The unthinkable "disassociation" and "refusal of insurance" are happening to the world's only maritime hegemon. To be precise, the decline of US maritime hegemony did not begin today, but the attack on ships in the Red Sea by Houthi rebels has severely damaged the US-led maritime security order and the credibility of maritime hegemony, which will greatly accelerate this process.

The reasons for the US to attack the Houthi rebels in Yemen are numerous, but the reasons for not doing so are even more immediate and painful. The US is caught in a dilemma between maintaining its maritime hegemony and retreating from its strategic posture. On one hand, maritime hegemony is the cornerstone of US global hegemony. Maintaining the commitment to "freedom of navigation" and providing maritime security products are essential for the US to maintain its global hegemony. On the other hand, the Red Sea-Suez is not the main shipping route for US foreign trade. Some US media have even pointed out that the disruption of Red Sea shipping is beneficial for US energy exports to Europe. Given its own interests, the US does not seem to need to invest excessively in the region.

Moreover, the US is determined to disengage from the Middle East to strengthen its "Indo-Pacific Strategy". If it is drawn deeper into the Houthi rebels, it is obviously not in line with the strategic direction of focusing on containing China. To shrink, or to maintain maritime hegemony in the Red Sea? This contradiction is the deep reason why the US has been struggling with its stance on the Red Sea crisis for more than two months because a declining US maritime hegemony can no longer reduce resource investment while quickly resolving crises.

At the same time, this Red Sea crisis will also lead to a subversion of the global pattern of naval warfare.

First, the US, which was the first to use drones on the Afghan battlefield, is now experiencing setbacks from the challenges posed by drones. This reflects a revolution in naval warfare. Aided by the support of technological revolution, unmanned and intelligent operations have become the key to asymmetric competition at sea. Drones have become a convenient new tool for maritime blockades, while the integration of land, sea, air, and cyberspace has created an intelligence analysis and early warning platform for all-domain awareness. This has ushered in a "transparent era" for maritime operations. Maritime situational awareness technology is rewriting the existing deterrence paradigm of waiting for opportunity at chokepoints in the straits. In addition, the deployment and practical application of intelligent unmanned equipment will lower the threshold for warfare and bring about indiscriminate casualties.

Second, with the strengthening of naval deterrence, "regional denial" has become more difficult to achieve, and "land-based control of the sea" has replaced "sea-based control of the land" as the decisive factor in naval warfare. At present, US and UK attempts to destroy Houthi missile launchers and drone facilities through air strikes have not yielded significant results in degrading their long-range strike capabilities. The Houthis' weapons systems are characterized by dispersed and mobile deployment, making them difficult to eliminate short of US and UK ground operations. This poses a challenge to the existing maritime military hegemony of "overseas military bases + naval forces". This is why the US and Japan are working together to strengthen the “Southwest Islands Wall” and are keen to increase the number of military bases in the Philippines to reduce the risk of carrier battle groups and bases being targeted. Nevertheless, the presence of maritime hegemonic countries coming from distant seas will be weakened in the near seas and pushed further into distant waters.

Third, non-state actors will play a greater role in future maritime battlefield. The Houthis' naval capabilities are backed by state support and can be exploited by certain countries. The Houthis' declaration of "support for Palestine" has gained moral backing, which to some extent influences the world's perception of the attacks on ships in the Red Sea. As technology diffuses, the maritime combat capabilities and cognitive influence of non-state actors will continue to grow. Unlike traditional pirates or maritime smugglers, their involvement in shaping maritime security situations is continuous and intense. This could become a new variable in the maritime security competition between states, especially the major powers.

(The author is the Deputy Director of the Institute of Maritime Strategy at the China Institute of Contemporary International Relations)

No comments:

Post a Comment