1). “Why 5 Million People Live in America’s Hottest City”, Feb 28, 2024, RealLifeLore, duration of video 50:16, at < https://www.youtube.com/watch?

2). “In Era of Drought, Phoenix Prepares for a Future Without Colorado River Water”, Feb 7, 2019, Jim Robbins, Yale 360, at < https://e360.yale.edu/

3). “Andrew Ross: Phoenix: Lessons from the World’s Least Sustainable City”, Andrew Ross Lecture, Mar 15, 2012, original source piratetvseattle@gmail.com, Internet Archive, duration of video 1:25:01 at < https://archive.org/details/

~~ recommended by dmorista ~~

Introduction by dmorista: The news this morning has documented various tornadoes and severe thunderstorms that damaged / destroyed areas in Oklahoma and Nebraska, and the severe weather will move east over the next couple of days. These tornadoes are just one aspect of the various environmental challenges the U.S. and the world in general are facing. One over-arching phenomenon of the past 50 years (and longer actually) has been the rapid growth of urban areas in the South and Southwest. In general the Southern and Southwestern U.S. are much more at risk of environmental disasters than is the Northern States. The largest urban areas in the South and Southwest have all grown in size rapidly for decades now. These include San Diego/Tijuana, Los Angeles, and the San Francisco Bay area, all of which actually began to grow rapidly decades before decades before the newest crop of SunBelt Cities began to grow rapidly. These recent growth centers include the urban areas centered on Miami, Atlanta, Houston, Dallas/Fort Worth, and Phoenix. There is also a raft of medium sized sunbelt cities that have been growing rapidly.

Phoenix stands out for a couple of reasons. First, Phoenix is the hottest city in the United States and according to some sources has the hottest summer temperatures of any Northern Hemisphere city. Second, Phoenix has undergone the greatest amount of growth of any Sun Belt city, as Item 1)., “Why 5 Million People Live ….”, points out the population of the area was 65,000 in 1940 and it is now nearing 5 million. Finally, Phoenix faces extremely serious water supply issues.

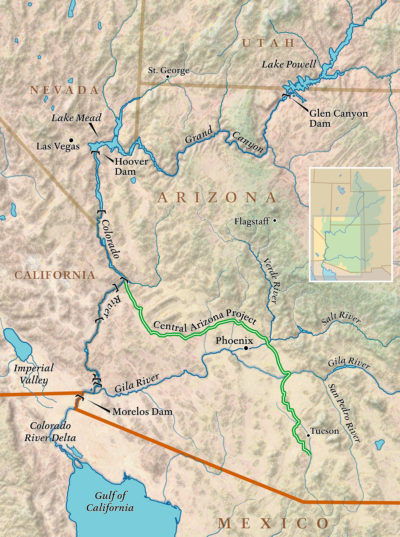

In Item 2)., “In Era of Drought, Phoenix Prepares ….”, the article points out that Phoenix that as of 2019 was obtaining the largest part of its water from the Salt River that supplies the Southern section of the urban area. At least now the Salt River is still providing adequate amounts of water. The Northern Part of the Phoenix urban area (the most affluent and influential part) uses large amounts of Colorado River Water, a source that is threatened by Global Warming isssues. Also the water from the Colorado River is pumped up 2,900 feet and moved to Phoenix and other aeas in Central and Southern Arizona via the Central Arizona Project (CAP). The CAP was completed and became operational in 1993. When the CAP was built a large electrical power generating station the Navajo Generating Station, a 2.25-gigawatt coal-fired power plant that was built to pump the water and provide power to other users in the area. The Navajo Generating Station was closed in 2019, and other power sources kept providing electricity to pump the water.

The Phoenix area uses 2.3 million acre feet of water per year. There are 90 million acre feet of ground water available in the immediate Phoenix area, but much of it is contaminated either by natural arsenic and chromium deposits and quite a bit by solvents used by the many armaments factories that were located in Phoenix in years past and that left several Superfund Sites leaking toxic materials or from older unlined landfills with hazardous waste. Much of that water would require expensive cleanup treatment but could be used for municipal water supplies with a theoretical yield of over 40 years at current usage rates. There is about 600 million acre feet of brackish ground water in the State of Arizona and it would require desalination (that has its own environmental problems). Item 1). points out that an Israeli company has proposed building a desalination water plant in Mexico along the shores of the Sea of Cortez. That has its own serious environmental costs and the Israeli Company's proposal would provide very expensive water. The Phoenix Water Services Department has also done the work to use several ground water reservoirs, using injection wells to fill them with different water, much of it surplus Colorado River Water that the city does not need at this time, banking it for future use.

Item 3)., “Andrew Ross: Phoenix: Lessons ….”, discusses the ethnography and sociology of Phoenix's water and other environmental issues. Ross thinks that the North Phoenix area will probably fortify their lives and use the latest environmental technologies while the poorer and largely non-white areas of South Phoenix will languish living with little or no help from the larger society to assist them in surviving the likely difficult days to come. Ross pointed out that as of 2012 the Phoenix area had not begun encouraging and installing large amounts of renewable energy capacity. As of a couple of years ago: “In 2022, 99% of Arizona's total electricity net generation was provided from 6 sources: natural gas (42%); nuclear power (29%); coal (12%); solar energy (10%); hydroelectric power (5%): and wind (1%).” So wind and solar accounted for 11%, nuclear power 29%, and hydroelectric 5%. Fossil Fuel sources provided 54%. While Nuclear and Hydroelectric power do not appreciably add to the Green House Gas amounts they certainly have their own significantm negative environmental impacts. (See, “Arizona State Energy Profile”, U.S. Energy Information Administration, at < https://www.eia.gov/state/

Phoenix has been subsidized by the Federal Government, both in the decisions to steer both military and high-tech industries to locate there, and in the building of the water infrastructure from the original building of the Hoover Dam onwards. Most recently the Biden Administration passed the Computer Sciences Act that subsidized different types of computer oriented factories in the U.S. Phoenix was chosen by both Intel and the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) for major production facilties. Intel and TSMC are investing over $60 bilion to build 3 major fabs, 2 by TSMC and 1 by Intel. The already existing chip fabs and the new ones use tremendous amounts of water, but clean up and reuse as much of it as possible. Nonetheless they do need sizeable amounts of water to be input each day.

Still, despite the latest investments, the biggest economic sector of Arizona and Phoenix is real estate development and speculation. These forces want to see a new major push to develop the land between Phoenix and Tucson, filling in large stretches of easily developed flat desert land. They forecast, and fervently wish, to create a giant mega urban area with a population of 9 or 10 million. Up until now the Phoenix area has managed to grow rapidly in ipopulation and economic activity while reducing the overall water usage back to the level last seen in 1957. It is unlikely that, if the climate continues to warm and surface water resources are further reduced, that Phoenix can continue to grow rapidly. If the groundwater around Arizona, or even sea water from the Sea of Cortez, are utilized more growth can be accomplished, but much of the advantage that Phoenix has in convincing companies to invest in the local area, that was due to low taxes and cheaper real-estate than in other places will be lost.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

In Era of Drought, Phoenix Prepares for a Future Without Colorado River Water

Once criticized for being a profligate user of water, fast-growing Phoenix has taken some major steps — including banking water in underground reservoirs, slashing per-capita use, and recycling wastewater — in anticipation of the day when the flow from the Colorado River ends. Fourth in a series.

The Hohokam were an ancient people who lived in the arid Southwest, their empire now mostly buried beneath the sprawl of some 4.5 million people who inhabit modern-day Phoenix, Arizona and its suburbs. Hohokam civilization was characterized by farm fields irrigated by the Salt and Gila rivers with a sophisticated system of carefully calibrated canals, the only prehistoric culture in North America with so advanced a farming system.

Then in 1276, tree ring data shows, a withering drought descended on the Southwest, lasting more than two decades. It is believed to be a primary cause of the collapse of Hohokam society. The people who had mastered farming dispersed across the landscape.

The fate of the Hohokam holds lessons these days for Arizona, as the most severe drought since their time has gripped the region. But while the Hohokam succumbed to the mega-drought, the city of Phoenix and its neighbors are desperately scrambling to avoid a similar fate — no easy task in a desert that gets less than 8 inches of rain a year.

“We are fully prepared to go into Tier 1, 2, and 3 emergency,” said Kathryn Sorensen, Phoenix’s water services director, referring to federally mandated cutbacks of Colorado River water as the levels of Lake Mead, the source of some of the city’s water, continue to drop. And what of the dreaded “dead pool,” the point at which the level in the giant man-made lake falls so low that water can no longer be pumped out?

“I can survive dead pool for generations,” says Sorensen, pointing to a host of conservation and water storage measures that have significantly brightened the city’s water outlook in an era of climate change and drought.

These days, Phoenix’s alternative water supplies are not dependent on the Colorado. But there’s a caveat. Phoenix may have enough water to secure its near-term future, but it still needs to build $500 million of infrastructure to pipe it to northern parts of the city that now rely on Colorado River water. And Phoenix may need the water sooner than it planned. “You could hit dead pool in four years,” Sorensen said. “That’s worst case.”

Many cities and towns in the Southwest — including Los Angeles, San Diego, and Albuquerque — are trying to figure out solutions to a dwindling Lake Mead, the key reservoir on the Colorado. One of the most ambitious efforts is a new $1.35 billion, 24-foot-wide tunnel — the so-called Third Straw — that Las Vegas drilled at the very bottom of Lake Mead to function like a bathtub drain. Las Vegas gets 90 percent of its water from the Colorado via the lake, which is located just east of the gambling and tourist mecca. In 2000, as the lake’s level dropped, the city placed a second, deeper straw to replace the original outtake. As the region moved into its second consecutive decade of drought and lake levels continued to drop, Las Vegas officials got more nervous and the third straw was completed in 2015; it should continue to siphon off water unless the lake dries up completely.

Supplying enough water to sustain a city this size in the desert has long been controversial.

In Arizona, the modern equivalent of the Hohokam irrigation system is the 17-foot-deep and 80-foot-wide concrete aqueduct called the Central Arizona Project, which carries water from the Colorado River to Phoenix, Tucson, and elsewhere. It was a feat of engineering when it was finished in 1993, snaking across the sere desert landscape for 336 miles as it pumps water up 2,900 feet in elevation. So much power is needed to flush this water along its route that the massive coal-fired Navajo Generating Plant was built to provide it.

Supplying enough water to sustain a city this size in the desert has long been controversial, and as Phoenix and its neighbors continue their unrelenting sprawl — Arizona’s population has more than tripled in the past 50 years, from 1.8 million in 1970 to 7.2 million today — the state has often been regarded as the poster child for unsustainable development. Now that Colorado River water appears to be drying up, critics are voicing their “I told you so’s.”

That’s a bad rap though, at least for Phoenix, according to Sorensen. The city is prepared to carry on with business as usual even if the last of the Colorado River water evaporates into the desert sky, depriving Phoenix of 40 percent of its water supply. City officials have been busy planning for this eventuality, and much of the responsibility for that has fallen to Sorensen.

As she stands behind her large desk on the 9th floor of the municipal building in the heart of downtown Phoenix, surrounded by windows that look out on glass office towers gleaming in the desert sun, Sorensen deftly handles questions about the city’s water future. On her desk sits a crystal ball, a joke gift that she says she wishes was real. She’s proud of the work she has done since she was appointed in 2013 — before that she served four years as head of Mesa, Arizona’s water department — although she admits it has been a challenge.

The Phoenix Water Services Department is one of the nation’s largest, with 1.5 million customers spread out across 540 square miles. It maintains 7,000 miles of water lines and 5,000 miles of sewer lines.

The Salt River is the single biggest source of water for metro Phoenix, and provides about 60 percent of its needs. It is a large desert river, some 200 miles long, that begins at the confluence of the snow-fed White and Black rivers, is joined by a series of perennial, spring-fed streams, and then meets the Verde River east of Phoenix.

Just after the turn of the 20th century, the first of four dams was constructed on the Salt for a growing Phoenix, and today those reservoirs are Phoenix’s main water supply. However, Phoenix’s north side gets only Colorado River water, and should that source dry up one day, constructing infrastructure to connect north Phoenix to new sources of water would cost a half-billion dollars. Funding for such a project would hardly be a fait accompli; in late December, the Phoenix City Council rejected a water rate increase to pay for the infrastructure expansion. The Salt and Gila rivers also may someday be severely impacted by climate change. “They could be affected by a mega-drought,” said Andrew Ross, a sociology professor at New York University and author of Bird on Fire: Lessons from the World’s Least Sustainable City. “They are in the bullseye of global warming, too.” Perennial streams could dry up and snowfall in Arizona’s White Mountains could dwindle, as it has done in the Rockies, further depriving the rivers of a steady supply of water.

“We’ve decoupled growth from water,” says a city official. “We use the same amount of water we did 20 years ago.”

Beyond the Salt River, Phoenix has undertaken some innovative water strategies. Among the first of these was the Arizona Water Bank. California is entitled to 4.4 million acre-feet of water a year from the Colorado, but because Arizona was not using its full allotment of 2.8 million acre-feet, its excess water was being slurped up by a perpetually thirsty California. So the water bank, a unique system of underground storage, was created in 1996 as a way to store Colorado River water that the state couldn’t use, rather than letting it flow through to California. It turned out to be a prescient move, but not for the reason it was created. In that era, few people foresaw the crash of the Colorado River system.

Arizona has since created seven water banks, largely in empty underground aquifers. A series of large pools has been built above the aquifers and, as water is pumped into them, it slowly leaches through a layer of gravel and rock and fills the aquifer. So far the water banks have cost the state $330 million, storing 3.6 million acre-feet in 28 sites across three counties — more than a year’s worth of Colorado River water.

One of the largest water banks is 40 miles west of Phoenix near the tiny town of Tonopah, Arizona. The nearly $20 million facility has 19 infiltration basins covering more than 200 acres. It was constructed alongside the Central Arizona Project canal, and a pipe delivers 300 cubic-feet-per-second of Colorado River water a day to fill the basins.

In addition, other aquifers underneath Phoenix are brimming with 90 million acre-feet of water, some natural and some pumped in — enough to last the city for years. One problem is that much of it is contaminated, both from natural sources of arsenic and chromium and from the city’s many Superfund sites, which include manufacturing sites polluted by industrial solvents and unlined landfills that contain hazardous waste. But Sorensen dismisses the cleanup challenges as surmountable. “As long as the contamination isn’t nuclear, we can fix it,” she says. “What matters here is that the water is wet.”

Phoenix also recycles almost every bit of wastewater that journeys through its system. The vast majority of it — more than 20 billion gallons of recycled water a year — goes to cool the Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant. Another 30,000 acre-feet is traded to an irrigation district as gray water to use on agricultural fields and the district, in turn, sends potable water from the Salt River to the city.

And the city is working on “toilet-to-tap” technology aimed at someday making sewage water so clean it will be drinkable. The technology for recycling wastewater into drinking water exists, but is only used in a few places, including San Diego. Arizona says it will play a role in its water supply some day — if, that is, the city can sell the idea to consumers.

Desalinization of seawater has long been floated as a possibility for Arizona, and much of the U.S. Southwest, and officials say it too will be part of Arizona’s water mix — someday. The process, which forces water through an extremely fine filter, is energy-intensive, extremely expensive, and a major environmental problem because of the waste it generates. Nonetheless, Arizona sits on top of 600 million acre-feet of brackish water, and officials have also considered treating water from the Gulf of California, nearly 200 miles to the southwest.

For now, though, Phoenix appears to have positioned itself well for a new era of drought. Sorensen credits the people of Phoenix for adapting to the desert by using far less water per capita. “We’ve decoupled growth from water,” she said. “We use the same amount of water that we did 20 years ago, but have added 400,000 more people.” In 2000, Some 80 percent of Phoenix had lush green lawns; now only 14 percent does. The city has done this by charging more for water in the summer. Per capita usage has declined 30 percent over the last 20 years. “That’s a huge culture change,” Sorensen says.

In fact, the decoupling of water from growth through conservation has taken place throughout the Lower Colorado Basin. “Actual municipal water use across the basin, with the exception of Utah, is declining, even as population rises,” said John Fleck, director of the University of New Mexico Water Resources Program. “Albuquerque has built its long-range plan around conserving more than its demand for decades to come, and Las Vegas’ demonstration of its ability to use less water is stunning.”

But while Phoenix and Las Vegas are pursuing conservation strategies as a partial solution to the withering of the Colorado River, others entities in the region aren’t. Much of conservative Arizona is in denial about what the potential drying of the West may mean, if they recognize it at all. “We’re just starting to acknowledge the volatile water reality,” said Kevin Moran, senior director of western water for the Environmental Defense Fund. “We’re just starting to ask the adaptation questions.” Ross, of New York University, argues that the biggest problem for Arizona is not climate change, but the denial of it, which keeps real solutions — such as reining in unsustainable growth or the widespread deployment of solar energy in this sun-drenched region — from being considered. “How you meet those challenges and how you anticipate and overcome them is not a techno-fix problem,” he said, “It’s a question of social and political will.”

All these well-intentioned measures may fall far short of being able to cope with a full-blown climate crisis.

So, for now, Arizona’s rampant growth continues. To the west of Phoenix a new tech city is emerging. Mt. Lemmon Holdings, a subsidiary of computer magnate Bill Gates’s investment firm, Cascade Holdings, has plans to built a “smart city,” for example, on the outskirts of Phoenix near the town of Buckeye. The new city, on 24,000 acres — about the same size as Paris — would have infrastructure for self-driving cars, hi-tech factories, and high-speed public wi-fi.

Meanwhile, the so-called Sun Corridor — 120 miles of Sonoran Desert between Phoenix and Tucson — is seen as the state’s next burgeoning megalopolis. It’s one of the fastest-growing regions in the country and its population of more than 5.5 million — anchored by Phoenix in the northwest and Tucson to the southeast — is expected to double by 2040.

And what about the water for this growth? Under state law, a developer must prove it has a 100-year supply for any new housing development. The primary solution for that has been for the Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District to fill or replenish aquifers where growth is planned — and the source for that is the precarious Colorado River water.

The reality, though, is that all of these well-intentioned measures may fall far short of being able to cope with a full-blown climate crisis. Someday the desert may reclaim what has been built here — as it did with the Hohokam.

Whether that unfolds remains to be seen. By Ross’s reckoning, the withering of Arizona will not be uniform, and those most affected will be the people least able to find alternatives, such as impoverished communities in South Phoenix.

“The well-resourced communities in the northeast are well set up,” for a drier future, said Ross. “And there are communities like South Phoenix that have been poisoned for decades that are not. It’s obvious who is going to suffer the most when the shortage really hits.”

“Here, we are all looking at Cape Town in shock,” said Taylor Hawes, of the Nature Conservancy’s Colorado River program, referring to the crisis last year when that South African city appeared on the brink of running out of water. “We’re not that far from that if things go south.”

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

NB note - please refer to the following link to watch “Andrew Ross: Phoenix: Lessons from the World’s Least Sustainable City”, Andrew Ross Lecture, Mar 15, 2012, original source piratetvseattle@gmail.com, Internet Archive, duration of video 1:25:01 at < https://archive.org/details/

No comments:

Post a Comment