~~ recommended by collectivist action ~~

Darien, Connecticut, sits pleasantly on the Fairfield County shoreline, where Henry Ford gifted his friend Charles Lindbergh a cottage less than five miles from Andrew Carnegie’s old summer estate. Darien, whose 21,000 residents favor the GOP and are 94% white, received in 2018 the honor of being named this nation’s wealthiest community. CEOs of JP Morgan Chase, PepsiCo, and Purdue Pharma occupy the surrounding wealth belt. Here, stereotypical elites relaxing on the Connecticut beachfront repeat “states’ rights” like a mantra and expose their devotion to a twice-defeated, now-rising empire.

Supposed moderates devoted to market-focused policy align themselves with the GOP to cut public services, narrow workers’ rights, and restrain democracy. The new confederacy, an alliance of reactionary capital and white reactionary populism, has seized the GOP. The new confederacy invites elites in union-dense blue states to share the antebellum dream of absolute exploitation, and often sets the limit on progress for backward Democrats. Connecticut Citizens Defense League, Connecticut Business and Industry Association, and the Yankee Institute share command here of the country club Right. Opposite them, organized labor anchors an emergent Third Reconstruction consensus, which leads a united front of forces in offensive statewide fights with a Black-led multiracial working class base. For those invested in the current struggle against the New Confederacy, it’s useful to look back at the strategy and program which toppled the first confederacy..

News spread fast across plantations in the American south. Enslaved Black workers tracking current events in 1860 rapidly developed a widespread sense of an “emancipating army” marching south to enact “biblical vengeance.” Panic spread among white elites as they anticipated war. Their terror fueled the Armageddon rumors and unlocked new space for open struggle led by Black workers.

In growing numbers, captive laborers freed themselves. Escapes and sabotage escalated to shutdowns. A slow-moving walk out “to stop the economy of the plantation system” helped create chaos in the old confederacy. Black labor seized the crises of war and secession as opportunities to win better conditions. “It was a general strike,” wrote W.E.B. Du Bois, “that involved directly in the end perhaps a half million people.”

Most strikers reached Union lines, and many tried to enlist. Their collective action narrowed Lincoln’s options: either enforce the Fugitive Slave Act during a war with its authors, or formalize the inevitable. Two bloody years had depleted Union ranks preceding the Emancipation Proclamation. Those it “freed” it also made eligible for military service.

The “royal rebellion” bled out from its points of southern production. Nearly two hundred thousand free Black workers then returned in regiments to crush the slaveowners’ army. Labor was the war’s root and protagonist. When the planters fell, free Black and poor white workers made up the only class left in the south loyal enough to govern.

By shutting down plantations and freeing themselves, enslaved Black workers compelled federal forces in favor of democracy and against white dictatorship. Black labor’s resistance grew into an uprising, and America reaped its second revolutionary war.

Northern business and southern labor formed a de facto alliance against planter counterrevolution. Factory owners with new political sway over plantations controlled raw materials. By controlling steel, robber barons accumulated great wealth in the postwar rail rush. Workers, whose interest remained in democracy, concurred with industrialists’ aim to strip planters of power.

This united front included small capitalists chasing a state-planned economic boom, along with middle class reformers and wealthy philanthropists. This united front wasn’t a self-conscious alliance but rather an objective fact, and came to occupy political space everywhere the old confederacy wasn’t. Backward forces within the front pumped the brakes, advanced forces pressed the gas, and both fought to steer.

Industrialists were profit-motivated against slavery, and competed with radicals for leadership of this reconstruction united front. Fearing workers’ economic power, northern business used moderates in congress to reinstall planters as wage-paying land barons. The Freedmen's Bureau, which tended to lean toward labor in contract disputes with slaveowners-turned-employers, expropriated planter property for redistribution. These unlikely allies had different approaches to their present common enemy.

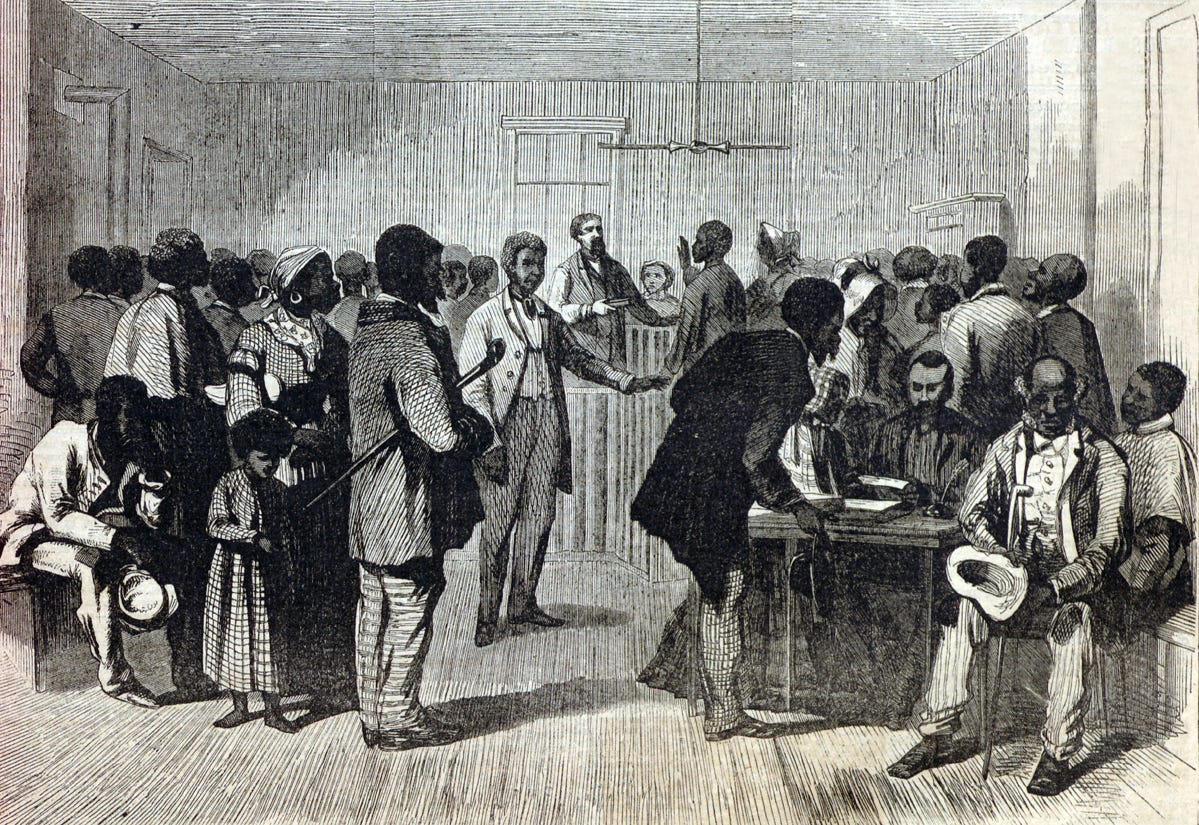

Du Bois credited a radical coherence of Republicans, trade unionists, and 48ers (immigrants from Europe who participated in the wave of revolutionary activity in 1848) for the advanced program that shaped the Bureau. These organizations and individuals he collectively called “the abolition-democracy” became the united front’s fighting edge. The Republican Party’s militant auxiliary, the Union League, went south in 1867 for a massive voter registration campaign. Newly enfranchised Black men and their still disenfranchised communities formed self-sustaining chapters which engaged in a variety of struggles.

Black workers in the south were highly organized, holding League meetings in secret to evade the Ku Klux Klan while advancing an historic wave of progress. Their strategy involved picking workplace fights with abusive rural bosses who beat workers and stole their wages. The League helped armed workers with the ballot to defend their gains while leading on offense with the strike weapon.

Radicals in congress made race-based voter suppression a constitutional crime with passage of the 15th amendment. As a result, eight months later, Black members of the League helped deliver big victories to Republicans in the 1870 midterms. Poll turnout during the 1872 presidential race was 80%, the highest in U.S. history, securing the Presidency for Grant, a powerful ally against planter violence.

Economically independent Black workers were harder to exploit, but industrialists needed their labor for a modern wage system in the south. Millions of experienced rural workers demanded proprietorship to revive the means of cultivation. Abiding land reform, northern business took the agrarian machinery out of planter hands and brought it back online. Free Black workers gained most where capitalists, disorganized by internal rivalry, faced grassroots organization.

The forces of “abolition democracy” got the ballot and elected themselves. Rewriting state constitutions, over fifteen hundred Black officeholders established the right to a quality education, a fair trial, and in North Carolina, to the “fruits of [one’s] own labor.” Workers’ governing power expanded as economic relations capsized. Free Black workers with the backing of the Army seized the confederate means of production and key limbs of the state.

Unable to win in the streets, the planters sowed the defeat of the pro-democracy united front in back rooms. Rutherford B. Hayes won the 1876 electoral college and popular vote, but Samuel J. Tilden, his pro-planter Democrat opponent, disputed the result and refused to step aside. To stay ahead of planters threatening violence, a congressional committee decided the outcome through internal deals.

Democrats offered to concede the election in exchange for Hayes ending Reconstruction, and northern business pressured committee Republicans to go along. Multi-racial democracy wasn’t worth war to the moderate, and gaining the presidency was easily worth betraying it.

Hayes withdrew troops and Democrats smoothly took power. The U.S. south again devolved toward slavery as planters mostly recaptured Bureau-seized land. Once the southern white bourgeoisie was chastened, northern industry abandoned its pact with multi-racial labor. That Black Americans today hold just 8% of the wealth whites do is partly a legacy of this 1877 betrayal.

Victory in the civil war, and in the political struggle after, meant significant gains: voting rights, land ownership, and labor protections extended to millions of formerly enslaved Black workers. The agrarian means of exploitation changed hands and transformed into the first broad basis of U.S. Black economic enfranchisement. Labor rights transformed work. Voting rights transformed state, local, and federal governments. These wins were secured offensively on site, and defended politically in state legislatures.

Today, the alliance remains. Southern reactionaries with a chokehold on state legislatures rollback rights that have been hardwon over the last 150 years. As often as not, they are happily funded by industrialists living in the North — many, perhaps, relaxing on the Darien coast. The triple fight for political power, labor power, and power over land, driven by a broad pro-democracy united front and led by Black labor, was once the force which broke a confederacy. Perhaps it can be again.

A Culture of Guns: Bang Bang, You’re Dead!

“Those fighting for gun violence prevention in the US — and that’s a growing number as the mass shootings continue — need to know that the number of gun homicides committed with guns made or sold in the US is even greater in México than in the US itself. Solidarity across borders is not just possible, it’s essential to end the scourge of gun violence plaguing us all.”

- John Lindsay-Poland, in an interview with the Mexico Solidarity Project

On Natural Vanguards

“I think those opposed to "vanguardism," or even those in favor of it, often have their own definitions of the term that are too narrow. For instance, at any given time, I find it useful to try to figure out the proportions of advanced, middle and backward among the general population in regards to politics.”

No comments:

Post a Comment