“In Era of Drought, Phoenix Prepares for a Future Without Colorado River Water”, “Part 4 of 5”, February 7, 2019, Jim Robbins, Yale Environment 360, at < https://e360.yale.edu/

“The West’s Great River Hits Its Limits: Will the Colorado Run Dry?”, “Part 1 of 5”, January 14, 2019, Jim Robbins, Yale Environment 360, at < https://e360.yale.edu/

Introduction by dmorista : Today, as a small but strong hurricane hit Florida, luckily at the least populated stretch of either the Gulf or Atlantic coasts of that state, seems like an odd time to post articles about drought and the disastrous situation of the Colorado River. But, what the various Sunbelt Land Speculators and Boosters don't want the public to know, is that conditions in these hot dry regions with their wildfire problems, and the Hurricane, tornado, and flood menaced lands of the Southeastern U.S. are just opposite sides of the same coin. And to a massive degree these ongoing situations, in which millions of people are moving from expensive Coastal Cities with less extreme conditios, to much more disaster prone, hot, and often reactionary controlled places; where housing is cheaper. This is, to a significant degree the consequence of the near complete lack of public investment in housing over decades, while private housing is the norm and has been subsidized in a wide variety of ways to the tune of hundreds of billions if not trillions of dollars. Compare the grim ugly public housing built in American cities during the period from the 1930s to the 1960s with the pubic housing of Vienna, Austria. Most of that housing (built during the period when the Austrian Communist Party controlled Vienna, that amounts to nearly ½ of Vienna's housing) is very well liked by the populace. There are waiting lines to get into such places as the Karl-Marx-Hof (English: Karl Marx Court). In the U.S. rich and powerful syndicates of land speculators and developers work together with extreme reactionary elements to direct land use and transportation policies, that enrich them, while moving millions of people into hot, too dry or too stormy, and otherwise disaster prone areas.

The First article here “In Era of Drought, ….” (though 4th in the Yale Environment 360 Series), looks at ways that various cities in the Colorado River Basin are adapting to the hotter drier future they now realize is pretty much inevitable. While the focus is on Phoenix and its environs in Arizona the article notes that:

“Many cities and towns in the Southwest — including Los Angeles, San Diego, and Albuquerque — are trying to figure out solutions to a dwindling Lake Mead, the key reservoir on the Colorado. One of the most ambitious efforts is a new $1.35 billion, 24-foot-wide tunnel — the so-called Third Straw — that Las Vegas drilled at the very bottom of Lake Mead to function like a bathtub drain. Las Vegas gets 90 percent of its water from the Colorado via the lake, which is located just east of the gambling and tourist mecca. In 2000, as the lake’s level dropped, the city placed a second, deeper straw to replace the original outtake. As the region moved into its second consecutive decade of drought and lake levels continued to drop, Las Vegas officials got more nervous and the third straw was completed in 2015; it should continue to siphon off water unless the lake dries up completely.” (Emphases added).

Phoenix itself has been working on a variety of other stratagems to try to ensure its water supply in the future. These include a shift to the Salt River as the urban area's main water supply and a variety of other measures including a reduction of thirsty grass lawns from 80% of homes to only 14% today:

“Phoenix has undertaken some innovative water strategies. Among the first of these was the Arizona Water Bank. California is entitled to 4.4 million acre-feet of water a year from the Colorado, but because Arizona was not using its full allotment of 2.8 million acre-feet, its excess water was being slurped up by a perpetually thirsty California. So the water bank, a unique system of underground storage, was created in 1996 as a way to store Colorado River water that the state couldn’t use, rather than letting it flow through to California. It turned out to be a prescient move, but not for the reason it was created. In that era, few people foresaw the crash of the Colorado River system.

“Arizona has since created seven water banks, largely in empty underground aquifers. A series of large pools has been built above the aquifers and, as water is pumped into them, it slowly leaches through a layer of gravel and rock and fills the aquifer. So far the water banks have cost the state $330 million, storing 3.6 million acre-feet in 28 sites across three counties — more than a year’s worth of Colorado River water. ….

“In addition, other aquifers underneath Phoenix are brimming with 90 million acre-feet of water, some natural and some pumped in — enough to last the city for years. One problem is that much of it is contaminated, both from natural sources of arsenic and chromium and from the city’s many Superfund sites, which include manufacturing sites polluted by industrial solvents and unlined landfills that contain hazardous waste. But Sorensen dismisses the cleanup challenges as surmountable. 'As long as the contamination isn’t nuclear, we can fix it,' she says. 'What matters here is that the water is wet.' (Emphasis added)

“Phoenix also recycles almost every bit of wastewater that journeys through its system. The vast majority of it — more than 20 billion gallons of recycled water a year — goes to cool the Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant. Another 30,000 acre-feet is traded to an irrigation district as gray water to use on agricultural fields and the district, in turn, sends potable water from the Salt River to the city. ….

“Desalinization of seawater has long been floated as a possibility for Arizona, and much of the U.S. Southwest, and officials say it too will be part of Arizona’s water mix — someday. The process, which forces water through an extremely fine filter, is energy-intensive, extremely expensive, and a major environmental problem because of the waste it generates. Nonetheless, Arizona sits on top of 600 million acre-feet of brackish water, and officials have also considered treating water from the Gulf of California, nearly 200 miles to the southwest. ….

“But while Phoenix and Las Vegas are pursuing conservation strategies as a partial solution to the withering of the Colorado River, others entities in the region aren’t. Much of conservative Arizona is in denial about what the potential drying of the West may mean, if they recognize it at all. 'We’re just starting to acknowledge the volatile water reality,' said Kevin Moran, senior director of western water for the Environmental Defense Fund. 'We’re just starting to ask the adaptation questions.' Ross, of New York University, argues that the biggest problem for Arizona is not climate change, but the denial of it, which keeps real solutions — such as reining in unsustainable growth or the widespread deployment of solar energy in this sun-drenched region — from being considered.” (Emphases added)

The second article, that provides an excellent summary of the issues that the River Basin States and Mexico face, is posted here, and points out that:

“Nature, in fact, has been given short shrift all along the 1,450-mile-long Colorado. In order to support human life in the desert and near-desert through which it runs, the river is one of the most heavily engineered waterways in the world. Along its route, water is stored and siphoned, routed and piped, with a multi-billion dollar plumbing system — a 'Cadillac Desert,' as Marc Reisner put it in the title of his landmark 1986 book. There are 15 large dams on the main stem of the river, and hundreds more on the tributaries.

“The era of tapping the Colorado River, though, is coming to a close. This muddy river is one of the most contentious in the country — and growing more so by the day. It serves some 40 million people, and far more of its water is promised to users than flows between its banks — even in the best water years. And millions more people are projected to be added to the population served by the Colorado by 2050. (Emphasis added)

“The hard lesson being learned is that even with the Colorado’s elaborate plumbing system, nature cannot be defied. If the over-allocation of the river weren’t problem enough, its best flow years appear to be behind it. The Colorado River Basin has been locked in the grip of a nearly unrelenting drought since 2000, and the two great water savings accounts on the river — Lake Mead and Lake Powell — are at all-time lows. ….

“Most of the water in the Colorado comes from snow that falls in the Rockies and is slowly released, a natural reservoir that disperses its bounty gradually, over months. But since 2000, the Colorado River Basin has been locked in what experts say is a long-term drought exacerbated by climate change, the most severe drought in the last 1,250 years, tree ring data shows. Snowfall since 2000 has been sketchy — last year it was just two-thirds of normal, tied for its record low. With warmer temperatures, more of the precipitation arrives as rain, which quickly runs off rather than being stored as mountain snow. Many water experts are deeply worried about the growing shortage of water from this combination of over-allocation and diminishing supply.

“There is tree ring data to show that multi-decadal mega-droughts have occurred before, one that lasted, during Roman Empire times, for more than half a century. The term drought, though, implies that someday the water shortage will be over. Some scientists believe a long-term, climate change-driven aridification may be taking place, a permanent drying of the West. That renders the uncertainty of water flow in the Colorado off the charts. While not ruling out all hope, experts have abandoned terms like “concerned” and “worrisome” and routinely use words like 'dire' and 'scary.' ”

In Era of Drought, Phoenix Prepares for a Future Without Colorado River Water

Once criticized for being a profligate user of water, fast-growing Phoenix has taken some major steps — including banking water in underground reservoirs, slashing per-capita use, and recycling wastewater — in anticipation of the day when the flow from the Colorado River ends. Fourth in a series.

The Hohokam were an ancient people who lived in the arid Southwest, their empire now mostly buried beneath the sprawl of some 4.5 million people who inhabit modern-day Phoenix, Arizona and its suburbs. Hohokam civilization was characterized by farm fields irrigated by the Salt and Gila rivers with a sophisticated system of carefully calibrated canals, the only prehistoric culture in North America with so advanced a farming system.

Then in 1276, tree ring data shows, a withering drought descended on the Southwest, lasting more than two decades. It is believed to be a primary cause of the collapse of Hohokam society. The people who had mastered farming dispersed across the landscape.

The fate of the Hohokam holds lessons these days for Arizona, as the most severe drought since their time has gripped the region. But while the Hohokam succumbed to the mega-drought, the city of Phoenix and its neighbors are desperately scrambling to avoid a similar fate — no easy task in a desert that gets less than 8 inches of rain a year.

“We are fully prepared to go into Tier 1, 2, and 3 emergency,” said Kathryn Sorensen, Phoenix’s water services director, referring to federally mandated cutbacks of Colorado River water as the levels of Lake Mead, the source of some of the city’s water, continue to drop. And what of the dreaded “dead pool,” the point at which the level in the giant man-made lake falls so low that water can no longer be pumped out?

“I can survive dead pool for generations,” says Sorensen, pointing to a host of conservation and water storage measures that have significantly brightened the city’s water outlook in an era of climate change and drought.

These days, Phoenix’s alternative water supplies are not dependent on the Colorado. But there’s a caveat. Phoenix may have enough water to secure its near-term future, but it still needs to build $500 million of infrastructure to pipe it to northern parts of the city that now rely on Colorado River water. And Phoenix may need the water sooner than it planned. “You could hit dead pool in four years,” Sorensen said. “That’s worst case.”

Many cities and towns in the Southwest — including Los Angeles, San Diego, and Albuquerque — are trying to figure out solutions to a dwindling Lake Mead, the key reservoir on the Colorado. One of the most ambitious efforts is a new $1.35 billion, 24-foot-wide tunnel — the so-called Third Straw — that Las Vegas drilled at the very bottom of Lake Mead to function like a bathtub drain. Las Vegas gets 90 percent of its water from the Colorado via the lake, which is located just east of the gambling and tourist mecca. In 2000, as the lake’s level dropped, the city placed a second, deeper straw to replace the original outtake. As the region moved into its second consecutive decade of drought and lake levels continued to drop, Las Vegas officials got more nervous and the third straw was completed in 2015; it should continue to siphon off water unless the lake dries up completely.

Supplying enough water to sustain a city this size in the desert has long been controversial.

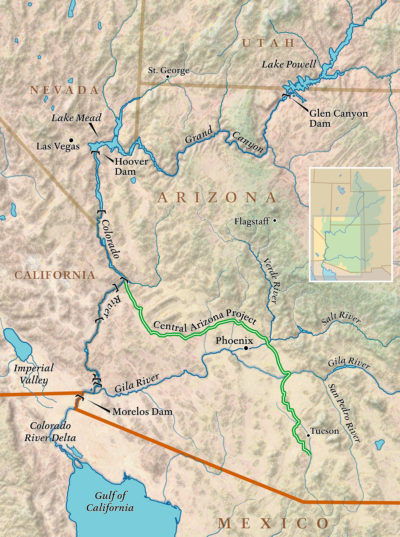

In Arizona, the modern equivalent of the Hohokam irrigation system is the 17-foot-deep and 80-foot-wide concrete aqueduct called the Central Arizona Project, which carries water from the Colorado River to Phoenix, Tucson, and elsewhere. It was a feat of engineering when it was finished in 1993, snaking across the sere desert landscape for 336 miles as it pumps water up 2,900 feet in elevation. So much power is needed to flush this water along its route that the massive coal-fired Navajo Generating Plant was built to provide it.

Supplying enough water to sustain a city this size in the desert has long been controversial, and as Phoenix and its neighbors continue their unrelenting sprawl — Arizona’s population has more than tripled in the past 50 years, from 1.8 million in 1970 to 7.2 million today — the state has often been regarded as the poster child for unsustainable development. Now that Colorado River water appears to be drying up, critics are voicing their “I told you so’s.”

That’s a bad rap though, at least for Phoenix, according to Sorensen. The city is prepared to carry on with business as usual even if the last of the Colorado River water evaporates into the desert sky, depriving Phoenix of 40 percent of its water supply. City officials have been busy planning for this eventuality, and much of the responsibility for that has fallen to Sorensen.

As she stands behind her large desk on the 9th floor of the municipal building in the heart of downtown Phoenix, surrounded by windows that look out on glass office towers gleaming in the desert sun, Sorensen deftly handles questions about the city’s water future. On her desk sits a crystal ball, a joke gift that she says she wishes was real. She’s proud of the work she has done since she was appointed in 2013 — before that she served four years as head of Mesa, Arizona’s water department — although she admits it has been a challenge.

The Phoenix Water Services Department is one of the nation’s largest, with 1.5 million customers spread out across 540 square miles. It maintains 7,000 miles of water lines and 5,000 miles of sewer lines.

The Salt River is the single biggest source of water for metro Phoenix, and provides about 60 percent of its needs. It is a large desert river, some 200 miles long, that begins at the confluence of the snow-fed White and Black rivers, is joined by a series of perennial, spring-fed streams, and then meets the Verde River east of Phoenix.

Just after the turn of the 20th century, the first of four dams was constructed on the Salt for a growing Phoenix, and today those reservoirs are Phoenix’s main water supply. However, Phoenix’s north side gets only Colorado River water, and should that source dry up one day, constructing infrastructure to connect north Phoenix to new sources of water would cost a half-billion dollars. Funding for such a project would hardly be a fait accompli; in late December, the Phoenix City Council rejected a water rate increase to pay for the infrastructure expansion. The Salt and Gila rivers also may someday be severely impacted by climate change. “They could be affected by a mega-drought,” said Andrew Ross, a sociology professor at New York University and author of Bird on Fire: Lessons from the World’s Least Sustainable City. “They are in the bullseye of global warming, too.” Perennial streams could dry up and snowfall in Arizona’s White Mountains could dwindle, as it has done in the Rockies, further depriving the rivers of a steady supply of water.

“We’ve decoupled growth from water,” says a city official. “We use the same amount of water we did 20 years ago.”

Beyond the Salt River, Phoenix has undertaken some innovative water strategies. Among the first of these was the Arizona Water Bank. California is entitled to 4.4 million acre-feet of water a year from the Colorado, but because Arizona was not using its full allotment of 2.8 million acre-feet, its excess water was being slurped up by a perpetually thirsty California. So the water bank, a unique system of underground storage, was created in 1996 as a way to store Colorado River water that the state couldn’t use, rather than letting it flow through to California. It turned out to be a prescient move, but not for the reason it was created. In that era, few people foresaw the crash of the Colorado River system.

Arizona has since created seven water banks, largely in empty underground aquifers. A series of large pools has been built above the aquifers and, as water is pumped into them, it slowly leaches through a layer of gravel and rock and fills the aquifer. So far the water banks have cost the state $330 million, storing 3.6 million acre-feet in 28 sites across three counties — more than a year’s worth of Colorado River water.

One of the largest water banks is 40 miles west of Phoenix near the tiny town of Tonopah, Arizona. The nearly $20 million facility has 19 infiltration basins covering more than 200 acres. It was constructed alongside the Central Arizona Project canal, and a pipe delivers 300 cubic-feet-per-second of Colorado River water a day to fill the basins.

In addition, other aquifers underneath Phoenix are brimming with 90 million acre-feet of water, some natural and some pumped in — enough to last the city for years. One problem is that much of it is contaminated, both from natural sources of arsenic and chromium and from the city’s many Superfund sites, which include manufacturing sites polluted by industrial solvents and unlined landfills that contain hazardous waste. But Sorensen dismisses the cleanup challenges as surmountable. “As long as the contamination isn’t nuclear, we can fix it,” she says. “What matters here is that the water is wet.”

Phoenix also recycles almost every bit of wastewater that journeys through its system. The vast majority of it — more than 20 billion gallons of recycled water a year — goes to cool the Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant. Another 30,000 acre-feet is traded to an irrigation district as gray water to use on agricultural fields and the district, in turn, sends potable water from the Salt River to the city.

And the city is working on “toilet-to-tap” technology aimed at someday making sewage water so clean it will be drinkable. The technology for recycling wastewater into drinking water exists, but is only used in a few places, including San Diego. Arizona says it will play a role in its water supply some day — if, that is, the city can sell the idea to consumers.

Desalinization of seawater has long been floated as a possibility for Arizona, and much of the U.S. Southwest, and officials say it too will be part of Arizona’s water mix — someday. The process, which forces water through an extremely fine filter, is energy-intensive, extremely expensive, and a major environmental problem because of the waste it generates. Nonetheless, Arizona sits on top of 600 million acre-feet of brackish water, and officials have also considered treating water from the Gulf of California, nearly 200 miles to the southwest.

For now, though, Phoenix appears to have positioned itself well for a new era of drought. Sorensen credits the people of Phoenix for adapting to the desert by using far less water per capita. “We’ve decoupled growth from water,” she said. “We use the same amount of water that we did 20 years ago, but have added 400,000 more people.” In 2000, Some 80 percent of Phoenix had lush green lawns; now only 14 percent does. The city has done this by charging more for water in the summer. Per capita usage has declined 30 percent over the last 20 years. “That’s a huge culture change,” Sorensen says.

In fact, the decoupling of water from growth through conservation has taken place throughout the Lower Colorado Basin. “Actual municipal water use across the basin, with the exception of Utah, is declining, even as population rises,” said John Fleck, director of the University of New Mexico Water Resources Program. “Albuquerque has built its long-range plan around conserving more than its demand for decades to come, and Las Vegas’ demonstration of its ability to use less water is stunning.”

But while Phoenix and Las Vegas are pursuing conservation strategies as a partial solution to the withering of the Colorado River, others entities in the region aren’t. Much of conservative Arizona is in denial about what the potential drying of the West may mean, if they recognize it at all. “We’re just starting to acknowledge the volatile water reality,” said Kevin Moran, senior director of western water for the Environmental Defense Fund. “We’re just starting to ask the adaptation questions.” Ross, of New York University, argues that the biggest problem for Arizona is not climate change, but the denial of it, which keeps real solutions — such as reining in unsustainable growth or the widespread deployment of solar energy in this sun-drenched region — from being considered. “How you meet those challenges and how you anticipate and overcome them is not a techno-fix problem,” he said, “It’s a question of social and political will.”

All these well-intentioned measures may fall far short of being able to cope with a full-blown climate crisis.

So, for now, Arizona’s rampant growth continues. To the west of Phoenix a new tech city is emerging. Mt. Lemmon Holdings, a subsidiary of computer magnate Bill Gates’s investment firm, Cascade Holdings, has plans to built a “smart city,” for example, on the outskirts of Phoenix near the town of Buckeye. The new city, on 24,000 acres — about the same size as Paris — would have infrastructure for self-driving cars, hi-tech factories, and high-speed public wi-fi.

Meanwhile, the so-called Sun Corridor — 120 miles of Sonoran Desert between Phoenix and Tucson — is seen as the state’s next burgeoning megalopolis. It’s one of the fastest-growing regions in the country and its population of more than 5.5 million — anchored by Phoenix in the northwest and Tucson to the southeast — is expected to double by 2040.

And what about the water for this growth? Under state law, a developer must prove it has a 100-year supply for any new housing development. The primary solution for that has been for the Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District to fill or replenish aquifers where growth is planned — and the source for that is the precarious Colorado River water.

The reality, though, is that all of these well-intentioned measures may fall far short of being able to cope with a full-blown climate crisis. Someday the desert may reclaim what has been built here — as it did with the Hohokam.

Whether that unfolds remains to be seen. By Ross’s reckoning, the withering of Arizona will not be uniform, and those most affected will be the people least able to find alternatives, such as impoverished communities in South Phoenix.

“The well-resourced communities in the northeast are well set up,” for a drier future, said Ross. “And there are communities like South Phoenix that have been poisoned for decades that are not. It’s obvious who is going to suffer the most when the shortage really hits.”

“Here, we are all looking at Cape Town in shock,” said Taylor Hawes, of the Nature Conservancy’s Colorado River program, referring to the crisis last year when that South African city appeared on the brink of running out of water. “We’re not that far from that if things go south.”

The West’s Great River Hits Its Limits: Will the Colorado Run Dry?

As the Southwest faces rapid growth and unrelenting drought, the Colorado River is in crisis, with too many demands on its diminishing flow. Now those who depend on the river must confront the hard reality that their supply of Colorado water may be cut off. First in a series.

The beginnings of the mighty Colorado River on the west slope of Rocky Mountain National Park are humble. A large marsh creates a small trickle of a stream at La Poudre Pass, and thus begins the long, labyrinthine 1,450-mile journey of one of America’s great waterways.

Several miles later, in Rocky Mountain National Park’s Kawuneeche Valley, the Colorado River Trail allows hikers to walk along its course and, during low water, even jump across it. This valley is where the nascent river falls prey to its first diversion — 30 percent of its water is taken before it reaches the stream to irrigate distant fields.

The Never Summer Mountains tower over the the valley to the west. Cut across the face of these glacier-etched peaks is the Grand Ditch, an incision visible just above the timber line. The ditch collects water as the snow melts and, because it is higher in elevation than La Poudre Pass, funnels it 14 miles back across the Continental Divide, where it empties it into the headwaters of the Cache La Poudre River, which flows on to alfalfa and row crop farmers in eastern Colorado. Hand dug in the late 19th century with shovels and picks by Japanese crews, it was the first trans-basin diversion of the Colorado.

Many more trans-basin diversions of water from the west side of the divide to the east would follow. That’s because 80 percent of the water that falls as snow in the Rockies here drains to the west, while 80 percent of the population resides on the east side of the divide.

The Colorado River gathers momentum in western Colorado, sea-green and picking up a good deal of steam in its confluence with the Fraser, Eagle, and Gunnison rivers. As it leaves Colorado and flows through Utah, it joins forces with the Green River, a major tributary, which has its origins in the dwindling glaciers atop Wyoming’s Wind River Mountains, the second largest glacier field in the lower 48 states.

The now sediment-laden Colorado (“too thick to drink, too thin to plow” was the adage about such rivers) gets reddish here, and earns its name – Colorado means “reddish.” It heads in a southwestern direction through the slick rock of Utah and northern Arizona, including its spectacular run through the nearly 280-mile-long Grand Canyon, and then on to Las Vegas where it makes a sharp turn south, first forming the border of Nevada and Arizona and then the border of California and Arizona until it reaches the Mexican border. There the Morelos Dam — half of it in Mexico and half in the United States — captures the last drops of the Colorado’s flow, and sends it off to Mexican farmers to irrigate alfalfa, cotton, and asparagus, and to supply Mexicali, Tecate, and other cities and towns with water.

While there are verdant farm fields south of the border here, it comes at a cost. The expansive Colorado River Delta — once a bird- and wildlife-rich oasis nourished by the river that Aldo Leopold described as a land of “a hundred green lagoons” — goes begging for water. And there is not a drop left to flow to the historic finish line at the Gulf of California, into which, long ago, the Colorado used to empty.

Nature, in fact, has been given short shrift all along the 1,450-mile-long Colorado. In order to support human life in the desert and near-desert through which it runs, the river is one of the most heavily engineered waterways in the world. Along its route, water is stored and siphoned, routed and piped, with a multi-billion dollar plumbing system — a “Cadillac Desert,” as Marc Reisner put it in the title of his landmark 1986 book. There are 15 large dams on the main stem of the river, and hundreds more on the tributaries.

The era of tapping the Colorado River, though, is coming to a close. This muddy river is one of the most contentious in the country — and growing more so by the day. It serves some 40 million people, and far more of its water is promised to users than flows between its banks — even in the best water years. And millions more people are projected to be added to the population served by the Colorado by 2050.

The hard lesson being learned is that even with the Colorado’s elaborate plumbing system, nature cannot be defied. If the over-allocation of the river weren’t problem enough, its best flow years appear to be behind it. The Colorado River Basin has been locked in the grip of a nearly unrelenting drought since 2000, and the two great water savings accounts on the river — Lake Mead and Lake Powell — are at all-time lows. An officially announced crisis could be at hand in the coming months.

Some scientists believe a long-term aridification driven by climate change may be taking place, a permanent drying of the West.

Meanwhile the Lower Basin states — Arizona, California, and Nevada — have, despite much debate, been unable to come up with a Drought Contingency Plan to keep water in Lake Mead below levels that would trigger a crisis and lead to mandatory cuts in water. And if the states do not agree on a plan by the end of this month, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman says she will step in and force hard decisions.

There are large, existential questions facing the 40 million people who depend on the river — there simply is not enough water for all who depend on it, and there will likely soon be even less.

Most of the water in the Colorado comes from snow that falls in the Rockies and is slowly released, a natural reservoir that disperses its bounty gradually, over months. But since 2000, the Colorado River Basin has been locked in what experts say is a long-term drought exacerbated by climate change, the most severe drought in the last 1,250 years, tree ring data shows. Snowfall since 2000 has been sketchy — last year it was just two-thirds of normal, tied for its record low. With warmer temperatures, more of the precipitation arrives as rain, which quickly runs off rather than being stored as mountain snow. Many water experts are deeply worried about the growing shortage of water from this combination of over-allocation and diminishing supply.

There is tree ring data to show that multi-decadal mega-droughts have occurred before, one that lasted, during Roman Empire times, for more than half a century. The term drought, though, implies that someday the water shortage will be over. Some scientists believe a long-term, climate change-driven aridification may be taking place, a permanent drying of the West. That renders the uncertainty of water flow in the Colorado off the charts. While not ruling out all hope, experts have abandoned terms like “concerned” and “worrisome” and routinely use words like “dire” and “scary.”

“These conditions could mean a hell of a lot less water in the river,” said Jonathan Overpeck, an interdisciplinary climate scientist at the University of Michigan who has extensively studied the impacts of climate on the flow of the Colorado. “We’ve seen declines in flow of 20 percent, but it could get up to 50 percent or worse later in this century.”

Even in rock-ribbed conservative areas, those who use the water of the Colorado say they are already seeing things they have never seen before — this year state officials in Colorado cut off lower-priority irrigators on the Yampa River, a tributary of the Green, and recreation had to be halted, for example — and have grudgingly come to believe “there is something going on with the climate.”

If water cuts are mandated, some states will be required to send others their allotted water, whether they have it to spare or not.

As the authors of a 2015 study on the region’s climate future put it: “Our results point to a remarkably drier future that falls far outside the contemporary experience of natural and human systems in Western North America, conditions that may present a substantial challenge to adaptation.”

So there are conventions and meetings and papers being written throughout the Colorado Basin, seeking an agreeable adaptive future for a river in crisis. One of the big rubs in an incredibly complex debate is this: In 1922, California was booming and helping itself to an increasing share of the water, while other states were growing far more slowly. The other basin states wanted to assure their share before California could suck it up and, with guidance from then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, created a Colorado River Compact that divvied up 15 million acre-feet of water — 7.5 million to the Upper Basin States and the same amount to Lower Basin States.

It’s well known now that this Law of the River was a product of irrational Manifest Destiny exuberance, a false premise based on unrealistic projections, because it was signed in one of the wettest periods on the river in centuries. Yet the actual amount apportioned among the states is more than 16 million acre-feet, 1.2 million acre-feet over the too-optimistic apportionment. These extravagant numbers are baked into the system, something known officially as a “structural deficit.”

St. George, Utah has been booming, with subdivisions and golf courses pushing into the desert. Support for aerial photographs provided by Lighthawk

This winter is make or break for the short term. A crisis is underway — record low flows were seen throughout last summer and fall. Another low- snow winter could light the fuse of a major crisis — an escalating crescendo of emergencies ending in a “compact call” when the lower basin states call on the upper basin states to send them their legally mandated allotment of water — whether they have it to spare or not. All of the players along the river are jockeying for “water security,” an oft-heard term in the region these days.

Cities from Tucson, Arizona, to St. George, Utah, to Denver are booming and need more water to keep growing. Municipal officials across the basin are apprehensive about the future of their growth economy in a time of an increasing likelihood of limits.

Another friction point is the fact that the Upper Basin States — Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah — still have “paper water,” meaning water owed to them by the 1922 compact, which they have not yet taken out of the river. And while many experts say no new straws should be dipped into the river to suck more water out, even if a state is entitled, there are plans afoot to do just that, setting up even more contention and wranglings.

Speculators are quietly buying up farms with water rights and holding them for the day that the price of water soars.

The future of farms and ranches that depend on Colorado River water is most uncertain. Agriculture uses about 80 percent of the Colorado’s flow to irrigate 6 million acres of crops, the largest share of which is alfalfa grown to feed cattle; cities use just 10 percent. While agriculture’s rights are senior — it staked the first claims and so, by law, is the last to lose its water in a crunch — if the going gets tough and cities start running out of water, political and economic clout would favor the millions of people who live there. In that case, agriculture would start losing some of its allotment, either willingly or unwillingly.

“You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to see that there is going to be pressure on your water,” says Mark Harris, general manager of the Grand Valley Water Users Association, a group of irrigators in western Colorado trying to adapt to a new era. “We have a target on our back.” Dewatering agriculture could lead not only to the buying and drying of farms, but the collapse of many small towns whose raison d’être is growing food.

And then there is the recreation industry, a $26 billion part of the Colorado River economy. Last year, raft companies had to reduce their season and cut back the number of trips on the river because of diminished flows.

Meanwhile, speculators and investors have waded into this complex “Chinatown”-like scenario, and are playing a quiet, though growing, role. Hedge funds and other interests, a breed of vulture capitalists, are quietly buying up farms with water rights, and holding them for the day things become more dire and the price of an acre-foot of water soars.

Lastly are the natural attributes of the Colorado River. The needs of fish, wildlife, and native flora have always been at the bottom of the priority list, lost to the needs of booming cities and thirsty crops. That’s changing, as a growing number of people and organizations are working to carve out a future for a more natural river — from the sandy beaches of the Grand Canyon, to the endangered fish along the river’s length, to the birds and jaguars of the Colorado River Delta in Mexico.

The bill for a century of over-optimism about what the river can provide is coming due. How the states will live within their shrinking water budget will depend on how severe the drought and drying of the West gets, of course. But however the climate scenario plays out, there is a good deal of pain and radical adaptation in store, from conservation, to large-scale water re-use, to the retirement of farms and ranches, and perhaps an end to some ways of life. Worst case, if the reservoirs ever hit “dead pool” — when levels drop too low for water to be piped out — many people in the region could become climate refugees.

“I hate to use the word dire, because it doesn’t do justice to the good-thinking people and problem solvers that exist in the basin, but I would say it is very serious,” said Brad Udall, a senior scientist at the Colorado Water Institute. “Climate change is unquantifiable and puts life- and economy-threatening risks on the table that need to be dealt with. It’s a really thorny problem.”

No comments:

Post a Comment