1). “A Federal Judge in Amarillo Could Effectively Ban the Abortion Pill. Why Does He Get to Make That Call?”, (A mysterious group with a Tennessee mailing address has filed a suit in the Panhandle city—guaranteeing it would be heard by Matthew Kacsmaryk, a longtime religious-right activist.), Feb 28, 2023, Grace Benninghoff, Texas Monthly, at < https://www.texasmonthly.com/

2). “The Trumpiest court in America: The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit is where law goes to die”, Dec 27, 2022, Ian Millhiser, Vox, at < https://www.vox.com/policy-

3). “She Wasn't Able to Get an Abortion. Now She's a Mom. Soon She'll Start 7th Grade”, Aug 14, 2023, Charlotte Alter (reporting from Clarksdale, Mississippi), Time, at < https://time.com/6303701/a-

Introduction by dmorista: Yesterday a panel of three judges from United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in Northern Texas, partially affirmed an earlier ruling to outlaw Mifepristone. That ruling was made by Matthew Kacsmaryk, the evil reactionary who presides over the Federal District Court in Amarillo, Texas. Kacsmaryk was “judge shopped” by a cabal of 4 Forced-Birth organizations and 4 Forced-Birth advocate physicians. He has now issued several reactionary / fascist rulings that have been applied nationally from his obscure post in the Panhandle of Texas. How can this obscure Forced-Birth Activist crackpot, nominated by Trump, given the green light by Leonard Leo and the Federalist Society, and shepherded through by Mitch McConnell the arch-reactionary leader of the Senate Republicans, be constantly making rulings that are applied nationally.

As Abortion Every Day pointed out yesterday evening: “The ruling, made by what Vox once called “the Trumpiest court in America,” would ban mifepristone from being mailed or prescribed via tele-health. (This would be a good time to re-read our explainer on the Comstock Act.) Law professor Greer Donley explains that if the decision is upheld, mifepristone would revert to its pre-2016 label in which the drug would only be approved through 7 weeks of pregnancy, and would require the medication to be prescribed and picked up in person: 'This would eliminate virtual abortion clinics, overwhelm brick-and-mortar clinics, increase the cost of care, and dramatically change the patient experience.' ” (Emphasis added)

Articles 1 & 2 address the background of how ultra-right extremist operatives are using the Federal Courts (particularly Kacsmaryk and the Fifth Circuit Appeals Court) to impose their agenda on the rest of the country. Of course some of the more astute Democrats and other commenters and analysts have pointed out that there is no way the U.S, Supreme Court, nor the lower courts have, of enforcing these reactionary rulings. Indeed there is now a considerable body of legal discussion of the need for States to defy the endless stream of far-right rulings by the current Partisan Hack Dominated U.S. Supreme Court. An article from a legal scholar at Santa Clara University starts off saying:

“In the United States, state governments have both a constitutional and an ethical duty to protect the health and safety of their citizens. The U.S. Supreme Court decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Ass’n v. Bruen, decided on June 23, interferes with the states’ ability to carry out that duty by purporting to create new constitutional limits on the power of state governments to enforce sensible gun control regulations.

“Bruen invalidated a New York law requiring individuals to demonstrate “proper cause” if they want to obtain a license to carry a concealed handgun in public. Although Bruen technically applies only to New York, it also appears to invalidate similar laws in California, Delaware, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island. This essay contends that state legislatures and state attorney generals should defy the Court’s decision in Bruen because their duty to protect the lives of their citizens takes precedence over their ostensible duty to follow misguided constitutional interpretations adopted by the Supreme Court. (Emphasis added)

“Article VI of the Constitution specifies that state legislators and state executive officials are 'bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support' the U.S. Constitution. The Supreme Court said in Cooper v. Aaron (1958) that Article VI requires state government officials to enforce the Constitution as interpreted by the Supreme Court. With due respect, Cooper v. Aaron was wrong on that point. Indeed, James Madison—arguably the most important architect of our Constitution—contended that state governments have a legitimate right to defy the Supreme Court when the Court oversteps its constitutional authority.

(Emphasis added) {See, “The Right of State Governments to Defy the Supreme Court”, July 6, 2022, David L. Sloss, Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, Santa Clara University, at < https://www.scu.edu/ethics-

And it should be added that the right-wingers have already begun to defy both Congressional Mandates, U.S. Supreme Court rulings, and rulings by their own state courts. Republican Regimes in Ohio, Alabama, and Missouri have already quit obeying Federal Laws and State and Federal Court Decisions. Many other states (about 25 now) have legalized marijuana; a substance that is still a Schedule 1 Narcotic, according to the Federal Government. The role of state governments (mostly right-wing in this article) in defying Federal Laws they disagree with is pointed out in another article:

“The breakdown of U.S. Supreme Court legitimacy may already have begun as the public perception of the court morphs from one of respectful observances of the law as interpreted by the nation’s top judicial scholars to a view of them as little more than political hacks in black robes. ….

“Various states, including Missouri, already are openly sidestepping federal marijuana laws, legalizing use of the drug even though the federal government outlaws marijuana as a Schedule I drug equivalent to heroin, LSD and methamphetamine.

“A steady stream of states, starting with Colorado, decided to defy the federal government to the point where federal authorities make minimal efforts to enforce their own laws these days. ….

“ 'We can’t trust Scotus (the Supreme Court) to protect the right to abortion, so we’ll do it ourselves,' Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom tweeted. 'Women will remain protected here.'

“The court’s politicization is no longer something justices can hide. The three most recent arrivals to the bench misled members of Congress by indicating they regarded Roe v. Wade as settled law, not to be overturned. Justice Clarence Thomas’ wife is an open supporter of former President Donald Trump and his efforts to subvert democracy.

“The Supreme Court has no police force or military command to impose enforcement of its rulings. Until now, the deference that states have shown was entirely out of respect for the court’s place among the three branches of government. If states choose simply to ignore the court following a Roe reversal, justices will have only themselves to blame for the erosion of their stature in Americans’ minds.” (Emphasis Added)

(See, “The day could be approaching when Supreme Court rulings are openly defied”, May 16, 2022, St. Louis Post-Dispatch editorial board (TNS), York Dispatch, at < https://www.yorkdispatch.com/

The progressive forces are late to the party, but the time has arrived to act. In particular the Mifepristone issue is one rich with more opportunities for The Democrats to actually do something effective. Several states bought up 5 year supplies of Mifepristone to continue to make that drug available. And shield laws now allow physicians to prescribe and provide Mifepristone and Misoprostol to be sent to women, even in the fascist stronghold of Texas. These actions should only be the beginning of Blue State initiatives. Red State operatives should be criminalized in the Blue States. Texas Abortion Bounty Hunters should be arrested on sight in the Blue States, and tried and imprisoned. If they participated in blocking abortion for a woman who was harmed or killed they should be charged with assault or murder, as appropriate.

Finally Article 3 is a very sad account of a girl who was raped when she was 12 and now has a baby son she must care for as she enters 7th grade. She had the misfortune of living in what is one of the most retrograde places on Earth, Mississippi. It is worth a read, but is pretty bleak.

xxxxxxxxxxxx

A Federal Judge in Amarillo Could Effectively Ban the Abortion Pill. Why Does He Get to Make That Call?

A mysterious group with a Tennessee mailing address has filed a suit in the Panhandle city—guaranteeing it would be heard by Matthew Kacsmaryk, a longtime religious-right activist.

The street address of the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine is a suite in a glossy office building tinted to reflect its surroundings. The building sits on the corner of South Taylor Street and Fifth Avenue in downtown Amarillo, mirroring the U.S. courthouse directly across the intersection that contains the chambers of federal judge Matthew Kacsmaryk. The AHM, which incorporated as a nonprofit organization in Texas last August, with a registered agent in Amarillo, is the lead plaintiff in a civil lawsuit moving through Kacsmaryk’s court that could outlaw the nation’s most common method of abortion, even in states whose legislatures have kept the procedure legal.

The complaint, filed in November, alleges that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration did not follow proper procedure when it approved mifepristone—the first in a two-step pill regimen for medication abortion—in September 2000. Some 22 years later, more than half of all abortions nationwide rely on that two-pill protocol, which medical experts say has proven to be both safe and effective. For those in Texas and other states where abortion bans have gone into effect since the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade last June, the pills have made it possible to evade those restrictions by ordering them online.

If Kacsmaryk sides with the plaintiffs—four anti-abortion groups and four doctors—mifepristone could be pulled from the market immediately. If that happens, it would be a first. Never before has a federal judge overruled the approval of a drug by the medical specialists employed by the FDA. But that’s the outcome that most legal experts and advocates for reproductive rights are expecting—and bracing for.

From the time the suit was filed in November, questions have been raised about the lead plaintiff and whether it has any legal standing to file suit in Amarillo. The AHM may have an Amarillo street address, but it lists a mailing address in Bristol, Tennessee, on its incorporation documents. The enigmatic group’s single-page website says it is dedicated to “upholding and promoting the fundamental principles of Hippocratic medicine.” Otherwise, the page is sparse, featuring images of ornate stone detailing, Greek lettering, a woman in safety glasses holding a beaker, and an etching of Hippocrates. There are no board members listed, no references to past work, no phone number or email address, and no information about who funds the group. In court, the organization is being represented by a team of seven attorneys from Alliance Defending Freedom, a powerful religious-right nonprofit group based in Scottsdale, Arizona.

“It feels as though lawyers have created this case in the forum in which they want to litigate it,” said David Donatti, a staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union of Texas who previously worked on challenges to Texas’s Senate Bill 8, the “abortion bounty” law. Donatti said it’s a classic example of “judge shopping,” in which plaintiffs manufacture reasons to file a case in a court where it will be heard by a judge who can be expected to rule in their favor.

Amarillo has become a hot spot for judge shopping, and that is because of Kacsmaryk. The 45-year-old, a graduate of Abilene Christian University and the University of Texas School of Law, was appointed to the federal bench in 2019 by President Donald Trump after years of religious-right activism. Before taking his seat on the U.S. District Court of the Northern District of Texas, Kacsmaryk worked for the First Liberty Institute, in Plano, a nonprofit organization that specializes in litigation that alleges violations of religious liberties. (Perhaps most famously, in a case heard by the U.S. Supreme Court, First Liberty successfully represented a couple who owned an Oregon bakery after they refused to make a cake for a same-sex couple.) “Someone who had his prior credentials—it’s hard to imagine a period much before 2017 when he might have been confirmed,” said Stephen Vladeck, a UT law professor and a nationally prominent expert on the federal courts.

While he was deputy general counsel for First Liberty, Kacsmaryk published a 2015 article in the National Catholic Register shortly ahead of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, which made same-sex marriage legal across the country. Arguing against the expansion of marriage rights, the future federal judge invoked the Catholic catechism and called homosexuality “disordered.” He also took the opportunity to express his disdain for the court’s past rulings protecting access to abortion and contraception, including Roe v. Wade. In that decision, he wrote in another 2015 article, the majority “found an unwritten ‘fundamental right’ to abortion hiding in the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the shadowy ‘penumbras’ of the Bill of Rights, a celestial phenomenon invisible to the non-lawyer eye.”

Kacsmaryk’s opposition to reproductive rights made him the ideal arbiter of the AHM’s attempt to ban the country’s most popular abortion method. So did his history of decisions on cases brought by right-wing plaintiffs. In his brief tenure on the bench, Kacsmaryk has ordered President Biden’s administration to reinstate the Trump-era Remain in Mexico policy, which requires asylum seekers to wait outside the U.S. while their claims are being processed. He’s declared Biden’s protections for transgender workers unlawful. And he’s ruled that parental consent must be required for teenagers to access contraception.

During his first Senate hearing in 2017, Kacsmaryk swore that his background as an activist would not affect his judicial decisions. “As a judge, I’m no longer in the advocate role,” he said, going on to vow that he would consider precedents from the Supreme Court and the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals—where appeals to his rulings would be heard—to be “binding.” In response to senators’ questions, he wrote, “I cannot think of any cases or category of cases requiring recusal on the grounds of conscience.” But if such a case did arise, he said, “I will fully and faithfully apply the law of recusal.” The only Republican who voted against confirming him in 2019, Senator Susan Collins, of Maine, didn’t buy it. She said that Kacsmaryk’s background, and his past comments on LGBTQ and reproductive rights, indicated “an inability to respect precedent and to apply the law fairly and impartially,” and that “Mr. Kacsmaryk has dismissed proponents of reproductive choice as ‘sexual revolutionaries,’ and disdainfully criticized the legal foundations of Roe v. Wade.”

Now, almost four years after he was confirmed, Kacsmaryk holds a uniquely powerful position on the federal bench. That’s because he is one of a handful of judges—most of them in Texas—who serve as sole judges for a division. In most districts around the country, cases are randomly distributed among the roster of judges, but in the Northern District of Texas, the chief judge, David Godbey—who divides up the cases—has opted to assign every case based on location. If plaintiffs file in Dallas, where there are multiple judges, they don’t know who will hear their case. In Amarillo, they are guaranteed to have their litigation heard by Kacsmaryk. Last September, Godbey, who was appointed by President George W. Bush, issued a “special order” amending the rules of the court: “The clerk of court is to assign each new case filed in the Amarillo Division to Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk.”

The rationale for this system is that plaintiffs and judges should not have to travel for hearings and trials. According to Vladeck, that’s a flimsy reason. Federal judges are routinely required to travel, he said, and that’s a small price to pay for a fairer system—one in which plaintiffs can’t pick their own judges. Judge shopping, which both liberal and conservative plaintiffs have used, has become a more pressing problem in the wake of Trump’s flood of right-wing judicial appointments during his four years in the White House. “It’s much easier,” Vladeck said, “to find a judge at one end of the ideological spectrum than it was ten or fifteen years ago.”

Lawyers, activists, and even the U.S. Department of Justice have expressed concern that Kacsmaryk has become a go-to judge for right-wing groups. While Kacsmaryk has spent the last few years hearing civil cases with broad national implications, that is not the norm for federal judges in Amarillo. His predecessor, Judge Marylou Robinson, appointed by Jimmy Carter in 1979, seldom handled litigation that garnered national political attention. She ruled on federal criminal cases filed in the Panhandle, civil cases with defendants based in Amarillo, and employment-discrimination cases against companies in the area—in Vladeck’s words, “cases with a real local flavor.”

It would be hard to find a purer example of judge shopping than the abortion-pill case, for several reasons. The lawsuit has been brought against the FDA, which is, of course, based in the Washington, D.C., area. Mifepristone cannot be prescribed in Texas because of the state’s abortion ban. And the AHM claims to represent doctors based all across the country. “It’s really easy to understand why [the suit] was filed in Amarillo,” Vladeck said. “There is no obvious factual reason for filing this in Amarillo. So there is only one compelling explanation”—the likelihood that Kacsmaryk will rule in favor of the plaintiffs.

Julie Marie Blake, a senior counsel for Alliance Defending Freedom who is a prosecuting attorney on the case, said in a telephone interview that Amarillo was an appropriate venue for the case. “The Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine has members all across the country,” she said, “including a lot of members in Texas, which is a centralized location.” She added that “a lot of the doctors in Texas are particularly active.” Three of the four doctors who are plaintiffs in the case work in California, Indiana, and Michigan, along with one from Texas: Dr. Shaun Jester, who practices in Dumas, about 45 minutes north of Amarillo. When I asked why the litigation was filed in Amarillo, rather than in another part of Texas, Blake’s colleague Donna Harrison, a doctor who’s the CEO of the Fort Wayne, Indiana–based American Association of Pro-life Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and who was also on the phone call, jumped in and said, “Why not?” Blake then reiterated: “We chose it because it’s a central location for all of our members.”

Although the AHM was incorporated in Amarillo only three months before the litigation was filed, Blake said the group has informally existed for about eight years as a “consortium” of five “partnering organizations”—anti-abortion groups based in Florida, Tennessee, Indiana, New York, and Pennsylvania. Blake said that it was only this past August that AHM got the paperwork together to incorporate in Amarillo, about a hundred yards from Judge Kacsmaryk’s chambers. While the alliance has no board or staff members listed anywhere, Harrison said that she is the chair of the board. I twice requested a list of board and staff members, and Hayden Sledge, Alliance Defending Freedom’s media relations specialist, sent me a link to the case page on the organization’s website. The page does not name the group’s board or staff members. When I asked for a list of people who work out of the Amarillo office, Sledge again sent a link to the case page.

The large stakes of Kacsmaryk’s decision have received increasingly feverish national attention as a ruling looms. If the judge orders a preliminary injunction to take mifepristone off the market, as the plaintiffs have requested, medication abortions will immediately become less effective and safe—and, at least temporarily, harder to get. Although it’s just half of the two-pill protocol that’s long been the gold standard for abortion care, mifepristone is known as the “abortion pill” because it terminates a pregnancy by blocking the body’s production of the hormone needed to keep an embryo or a fetus viable. The second pill, misoprostol, starts uterine contractions and expels the embryo or fetus. (Despite Texas’s abortion ban, misoprostol is still legal in the state because it’s also used to treat miscarriages and ulcers.) The two-pill regimen, if undertaken during the first ten weeks of pregnancy, has success rates that range from 91 to 99 percent. While misoprostol can be used alone—and often is, in places where mifepristone is inaccessible—it is only about 78 percent effective and more often has side effects such as cramping and nausea.

If Kacsmaryk orders mifepristone be pulled from the market, said Dr. Bhavik Kumar, medical director for primary and transgender care at the Houston-based Planned Parenthood Gulf Coast, “people will lose the option that is most effective.” That will be problematic for many of the Texans who travel to clinics in states where abortion is still legal. If patients take misoprostol alone and it doesn’t work, they may have to return to a clinic—if they have the time and money to do so—for either another dose of the pill or a surgical abortion. Meanwhile, the pregnancy will have progressed, making the abortion riskier. And the clinics, which have been overwhelmed since the demise of Roe v. Wade last June, will become even more congested. “It will be an immediate shock to the provision of care,” said Rabia Muqaddam, a senior staff attorney at the Center for Reproductive Rights in New York. “Texans are already traveling to access care,” she said. “The idea of limiting a safe method that they can sometimes access, that’s going to have a huge impact on Texans.”

While the potential harm to pregnant individuals is clear, the lawsuit in Kacsmaryk’s court is based on a murky claim that it’s the plaintiffs—the doctors—who are being harmed every day that mifepristone remains available. Typically, such a lawsuit would be based on a patient claiming harm—an adverse reaction to the drug, say. But there are no patients involved in this suit. Instead, the doctors argue that they are harmed because they have to give their patients additional care when they have adverse reactions to mifepristone, which has been proven to be safer to take than Tylenol. “This is a case where a doctor is speculating on what caused a patient to experience particular symptoms and then, against the informed judgment of millions of other health-care professionals, is seeking to change a national policy with huge significance for reproductive health,” said the ACLU’s Donatti.

The plaintiffs cite concerns about mifepristone’s safety as the driving force behind their lawsuit, claiming that hemorrhaging and infection are common side effects of the pill. But in the FDA’s list of possible side effects—which include nausea, abdominal cramping, and headaches—hemorrhaging and infection are logged as very rare. In court documents, the FDA says the incidence of hemorrhaging on the pill is 0.1 percent, while sepsis occurs 0.01 percent of the time (infections without sepsis occur 0.2 percent of the time).

The plaintiffs’ central claim is that the FDA rushed its approval of mifepristone under pressure from the Clinton administration. In the complaint, the AHM argues that when the FDA approved mifepristone through an accelerated approval process reserved for drugs “that treat serious conditions, and fill an unmet medical need,” the agency was out of line. The plaintiffs argue that pregnancy is not an “illness,” so the drug need not have gone through accelerated approval. (The “accelerated” process, in this case, meant that mifepristone hit the market in the U.S. after more than a decade’s worth of research and clinical trials; the drug had been prescribed in the United Kingdom and France since the late 1980s and early 1990s.)

Despite the sketchy claims made in the lawsuit, it would be a surprise to observers on both sides of the abortion debate if Kacsmaryk doesn’t rule for the plaintiffs. If he grants the preliminary injunction that the AHM has asked for, the case could eventually be tried in his court. (Cases of this magnitude sometimes take years to try.) In the meantime, a defendant in the case—most likely the FDA or Danco Laboratories, which manufactures mifepristone under the brand name Mifeprex —would probably appeal the decision to the Fifth Circuit in an effort to quickly get the drug back on the market. For abortion-rights supporters, that may not exactly raise hopes; the appeals court is overwhelmingly conservative. It is packed with right-wing activist judges appointed by Trump and George W. Bush, and it has upheld Kacsmaryk’s rulings in the past. After the Fifth Circuit, the next step for the defendants would be a Supreme Court appeal to lift the injunction. That court, too, is packed with right-wing activist judges appointed by Trump and Bush.

Kacsmaryk could issue a ruling any day now; this past Friday, February 24, was his deadline for arguments to be filed supporting and opposing the injunction request. One hundred and sixty-four groups and individuals across the country, on both sides of the abortion issue, have filed amicus briefs in the case. Forty-five state governments, the District of Columbia, and 67 members of Congress—along with doctors, activists, and former patients—have offered their input in the briefs. It’s unusual for so many outside parties to chime in on a case. But in the end, it might not matter how many weigh in. It all comes down to one judge in Amarillo.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

The Trumpiest court in America

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit is where law goes to die.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/71795586/874614596.0.jpg)

Trent Taylor says his cell, in a Texas psychiatric unit operated by the state’s prison system, was covered in human excrement. Feces smeared the window and streaked the ceiling. Someone had painted a shit swastika on the wall, alongside a smiley face. According to Taylor’s allegations in a federal lawsuit, there was such a thick layer of dried human dung on the floor of the cell that it made a crunching sound as he walked naked across the cell.

Taylor alleged that he was kept in this cell for four days, where he neither ate nor drank due to fears that the excrement, which was even packed inside the cell’s water faucet, would contaminate anything he consumed. Then, on the fifth day, he was moved to a bare, frigid cell with no toilet, water fountain, or bed. A clogged drain filled the new cell with choking ammonia films. With nowhere to relieve himself, Taylor held his urine for 24 hours before he could do so no longer. And then he had to sleep alone on the floor while covered in his own waste.

The Supreme Court eventually ruled 7–1 that Taylor’s lawsuit against the corrections officers who forced him to live in these conditions could move forward, and that lawsuit settled last February. But the Supreme Court had to intervene after an even more conservative court, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, attempted to shut down these claims against the prison guards.

A unanimous panel of three Fifth Circuit judges held that it was unclear whether the Constitution prevents prisoners from being forced to remain in “extremely dirty cells for only six days” — although, in what counts as an act of mercy in the Fifth Circuit, the panel did concede that “prisoners couldn’t be housed in cells teeming with human waste for months on end.”

This decision, in Taylor v. Stevens, is hardly aberrant behavior by the Fifth Circuit, which oversees federal litigation arising out of Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. The Fifth Circuit’s Taylor decision stands out for its casual cruelty, but its disregard for law, precedent, logic, and basic human decency is ordinary behavior in this court.

Dominated by partisans and ideologues — a dozen of the court’s 17 active judgeships are held by Republican appointees, half of whom are Trump judges — the Fifth Circuit is where law goes to die. And, because the Fifth Circuit oversees federal litigation arising out of Texas, whose federal trial courts have become a pipeline for far-right legal decisions, the Fifth Circuit’s judges frequently create havoc with national consequences.

The Fifth Circuit has, in recent months, declared an entire federal agency unconstitutional and stripped another of its authority to enforce federal laws protecting investors from fraud. It permitted Texas Republicans to effectively seize control of content moderation at social media sites like Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Less than a year ago, the Fifth Circuit forced the Navy to deploy sailors who defied an order to take the Covid vaccine, despite the Navy’s warning that a sick service member could sideline an entire vessel or force the military to conduct a dangerous mission to extract a Navy SEAL with Covid.

As Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote when the Supreme Court restored the military’s command over its own personnel, the Fifth Circuit’s approach wrongly inserted the courts “into the Navy’s chain of command, overriding military commanders’ professional military judgments.”

And this is just a small sample of the decisions the Fifth Circuit has handed down in 2022. Go back just a little further, and you’ll find things like a decision endangering the First Amendment right to protest, or another that seized control over much of the United States’ diplomatic relations with the nation of Mexico. In 2019, seven Fifth Circuit judges joined an opinion that, had it been embraced by the Supreme Court, could have triggered a global economic depression unlike any since the 1930s.

Its judges embrace embarrassing legal theories, and flirt with long discredited ideas — such as the since-overruled 1918 Supreme Court decision declaring federal child labor laws unconstitutional. They abuse litigants and even each other. During a 2011 oral argument, the Court’s then-chief judge, Edith Jones, told one of her few left-leaning colleagues to “shut up.”

And while the Fifth Circuit is so extreme that its decisions are often reversed even by the Supreme Court’s current, very conservative majority, its devil-may-care approach to the law can throw much of the government into chaos, and even destabilize our relations with foreign nations, before a higher authority steps in. Worse, the Fifth Circuit’s antics could very well be a harbinger for what the entire federal judiciary will become if Republicans get to replace more justices.

The median Fifth Circuit judge is very far to the right — more so than the Court’s current median justice, Brett Kavanaugh. But the typical Fifth Circuit judge would also be quite at home alongside a Republican stalwart like Justice Samuel Alito, or a more nihilistic justice like Neil Gorsuch.

How the Fifth Circuit became a far-right playground

Two generations ago, the Fifth Circuit was widely viewed as a heroic court by proponents of civil rights, handing down aggressive decisions calling for public school integration and protecting voting rights — even in the face of opposition from other, prominent judges.

Very soon after Brown v. Board of Education (1954) determined that racially segregated public schools violate the Constitution, a panel of federal judges in South Carolina handed down an influential opinion, in Briggs v. Elliott (1955), that effectively strangled Brown in its cradle. Brown, the court claimed in Briggs, “has not decided that the states must mix persons of different races in the schools or must require them to attend schools or must deprive them of the right of choosing the schools they attend.” To comply with Brown, Briggs suggested, a state must merely offer Black children the choice to attend white schools — and if those children choose to remain in segregated classrooms, that’s not a constitutional problem.

As a practical matter, these “freedom to choose” plans led to very little integration, in no small part because African American families knew full well what the Ku Klux Klan might do to them if they volunteered to send their children to a historically white school. Ten years after Briggs, the Fifth Circuit noted in United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education (1967), the South Carolina school system at the heart of the Briggs case was “still totally segregated.”

Jefferson County was authored by Judge John Minor Wisdom, arguably the greatest of the Fifth Circuit’s judges, whose name adorns the court’s building in New Orleans today. After watching Briggs’s approach fail Black children for 10 long years, Wisdom wrote a lengthy, statistics-laden opinion savaging Briggs and insisting that “the only school desegregation plan that meets constitutional standards is one that works.”

“The Brown case is misread and misapplied when it is construed simply to confer upon Negro pupils the right to be considered for admission to a white school,” Wisdom wrote. “The Constitution is both color blind and color conscious,” he wrote, anticipating modern-day attacks on affirmative action. It must be read “to prevent discrimination being perpetuated and to undo the effects of past discrimination.”

At the time, the Fifth Circuit’s jurisdiction extended over six Southern states, stretching from Texas to Florida (the court was split in half and three of these states were reassigned to a new Eleventh Circuit by a 1980 law), so the aggressive approach to desegregation laid out in Wisdom’s Jefferson County opinion bound many of the states where the need for public school integration was most urgent.

Beginning in the 1980s, however, Wisdom’s influence within his court began to fade. Republican President Ronald Reagan appointed a total of eight judges to the Fifth Circuit — one of whom was Edith Jones, a thirtysomething former general counsel to the Texas Republican Party. President George H.W. Bush added another four judges. The result was that, by 1991, Wisdom complained that his court’s approach to race in education was so harsh that it would even violate the separate-but-equal approach announced in the Supreme Court’s infamous Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) decision.

If any one decision captures the spirit of the post-Reagan, but pre-Trump Fifth Circuit, it’s that court’s decision in Burdine v. Johnson (2000). In that case, a man was convicted of murder and sentenced to die after his court-appointed lawyer slept through much of his trial. One witness recalled that the lawyer fell asleep as many as 10 times. Another testified that the lawyer “was asleep for long periods of time during the questioning of witnesses.”

And yet, a panel of Fifth Circuit judges that included Judge Jones initially voted to let this death sentence stand because it was unable to determine whether the lawyer “slept during the presentation of crucial, inculpatory evidence,” or merely through portions of the trial that the panel deemed unimportant. Eventually, the full Fifth Circuit reheard Burdine and held that the death row inmate at the heart of the case must be retried — but it did so over the dissents of five Fifth Circuit judges.

And the Fifth Circuit has only grown more conservative since these five judges determined that it was no big deal that a capital defendant’s lawyer couldn’t even remain awake throughout his trial.

Trump’s appointees turned the Fifth Circuit into a farce

When former President Donald Trump took office, the Fifth Circuit was already one of the most conservative courts in the country. It also had two vacancies due to a boneheaded decision by former Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Patrick Leahy (D-VT) to give Republican senators a veto power over anyone nominated to a federal judgeship in their home state — thus preventing President Barack Obama from filling these seats during his time in office.

To the first of these two seats, Trump appointed Don Willett, a libertarian provocateur known for speckling his opinions with the kind of platitudes that one might hear from a member of the John Birch Society, a member of the Tea Party, or a participant in the January 6 putsch. Sample quote: “Democracy is two wolves and a lamb voting on what to have for lunch. Liberty is a well-armed lamb contesting the vote.”

And then there was James Ho, the former law clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas who labeled abortion a “moral tragedy” in one of his first opinions as a judge. Ho’s very first opinion sought to implement a proposal he first announced in a 1997 op-ed to “abolish all restrictions on campaign finance.” The opinion declared that “big money in politics” was a “necessary consequence” of “big government in our lives.” It also claimed that our current government “would be unrecognizable to our Founders” because the Affordable Care Act exists.

Another Trump judge on the Fifth Circuit, Cory Wilson, published a series of columns in Mississippi newspapers that raise serious questions about his ability to apply the law impartially to Democrats and to LGBTQ Americans. Among other things, Wilson claimed that “intellectually honest Democrat[s]” are “very rare indeed.” He called President Obama a “fit-throwing teenager” because he opposed a Republican proposal to slash Medicaid funding and repeal Medicare and replace it with a voucher program. He wrote that “gay marriage is a pander to liberal interest groups and an attempt to cast Republicans as intolerant, uncaring and even bigoted.” And he also had a Twitter feed that often resembled Trump’s.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24276402/temp.png)

Another Trump judge on the Fifth Circuit, Kyle Duncan, spent much of his career as an anti-LGBTQ lawyer. He may be best known for an opinion he authored as a judge, which refused a transgender litigant’s request that Duncan use her proper pronouns.

Duncan also joined an opinion, authored by Trump-appointed Judge Kurt Engelhardt, which blocked a Biden administration rule requiring most workers to either get vaccinated against Covid-19 or take weekly Covid tests. The Supreme Court eventually struck this rule down under a legally dubious, judicially created legal doctrine called “major questions.”

But Engelhardt’s opinion makes this Supreme Court look sensible and moderate. Although federal law permits the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to issue emergency rules to protect workers from “exposure to substances or agents determined to be toxic or physically harmful,” Engelhardt made the extraordinary argument that the novel coronavirus — which has killed over a million Americans — does not qualify as a “substance or agent” that is “physically harmful.”

Nor did Engelhardt stop there. His most aggressive argument implies that the federal government’s power to regulate commerce does not extend to the workplace, which is the same argument the Supreme Court used in a discredited 1918 decision striking down federal child labor laws.

Trump, in other words, took a court that was already a reactionary outlier among the federal courts of appeal, and filled it with judges from the fringes of the legal profession. And those judges gleefully sow chaos throughout the law.

Why the Fifth Circuit in particular can cause so much chaos

One reason why the Fifth Circuit’s decline is so harmful to the nation as a whole is that it oversees federal litigation arising out of Texas.

That’s one part of a perfect storm: Texas’s Republican attorney general and other conservative litigants frequently bring challenges to Biden administration policies in Texas’s federal trial courts. And because those courts often permit plaintiffs to choose which judge will hear their lawsuits, these challenges frequently go before highly partisan judges who issue nationwide injunctions blocking that policy. And then those decisions, which frequently have glaring legal errors that would be obvious to many first-year law students, go to the Fifth Circuit.

This practice has been a particular thorn in the side of the Department of Homeland Security, as Texas has repeatedly obtained orders from Trump judges blocking the Biden administration’s immigration policies. One even forced the United States to change its diplomatic posture regarding Mexico.

One of the federal appeals’ courts most important roles is to keep a watchful eye over federal trial judges, and make sure they don’t issue disruptive, idiosyncratic decisions — or, at least, to make sure that those decisions don’t remain in effect for long. But the Fifth Circuit almost always operates like a rubber stamp for the Trumpiest judges, blessing even the most extreme decisions by trial judges who hope to sabotage Biden’s policies.

Just as often, the Fifth Circuit hands down decisions that seem to come out of nowhere, embracing legal theories that few lawyers have ever even heard of before, and that threaten to shut down much of the federal government and disrupt the nation’s economy. Consider, for example, Community Financial Services v. CFPB (2022), a decision by three Trump judges (Willett, Engelhardt, and Wilson), which declared the entire Consumer Financial Protection Bureau unconstitutional.

The Fifth Circuit’s opinion, by Wilson, claims that the agency is unlawful because of the unusual way that it is funded — rather than receiving an annual appropriation from Congress, the CFPB receives a portion of the funds raised by the Federal Reserve. Wilson claims that this funding structure “violates the Constitution’s structural separation of powers.”

But he’s just plain wrong about that, and his legal reasoning was explicitly rejected by the Supreme Court more than eight decades ago. Wilson relied on a provision of the Constitution stating that “no money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” But, as the Supreme Court held in Cincinnati Soap Co. v. United States (1937), this provision “means simply that no money can be paid out of the Treasury unless it has been appropriated by an act of Congress.”

Because there is an Act of Congress creating the CFPB and its funding structure, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, the CFPB is constitutional. Wilson’s opinion relies on a fantasy constitution that does not exist.

Three years before its CFPB decision, seven Fifth Circuit judges signed onto another opinion that would have destroyed another entire federal agency — and potentially triggered a worldwide economic depression in the process.

The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) was created in 2008 to deal with the mortgage crisis that triggered a historic recession, and that very well could have led to a second Great Depression if the FHFA had not acted. Over the course of the next several years, the FHFA presided over tens of billions of dollars worth of transactions intended to prop up the US mortgage system and ensure that the American housing market did not collapse.

About a dozen years after the FHFA was created, however, the Supreme Court determined that federal agencies may not be led by a single individual who cannot be fired at will by the president. By law, the FHFA director enjoyed some protections against being fired, and there’s no question that this decision required her to be stripped of these protections.

But in Collins v. Mnuchin (2019), seven Fifth Circuit judges joined an opinion by Judge Willett, which argued that this minor constitutional violation — a violation the Supreme Court didn’t even recognize until years after the FHFA was established — renders everything the FHFA has ever done invalid. When a plaintiff who is injured in any way by one of the FHFA’s actions files a federal lawsuit challenging that action, Willett claimed, the “action must be set aside.”

The immediate impact of Willett’s opinion, had it taken effect, would have been to force the FHFA to unravel more than $124 billion worth of transactions it undertook to rescue the US housing market — more than the gross domestic product of the entire nation of Ecuador. But Willett’s opinion would have gone even further than that, because it would have permitted suits invalidating literally anything the FHFA had ever done since its creation in 2008.

In any event, the Collins case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court, where the justices voted 8 to 1 to reject Willett’s approach. Only Justice Neil Gorsuch thought that toying with an economic depression was a good idea.

But even when the Supreme Court does step in, eventually, to reverse the Fifth Circuit, it often drags its feet. When a notoriously partisan federal trial judge ordered the Biden administration to reinstate much of Trump’s border policy, and the Fifth Circuit rubber stamped that decision, the Supreme Court waited 11 months to intervene — leaving the lower court’s decisions imposing a defeated president’s policies on the nation in place the entire time. A similar drama played out over immigration enforcement.

The result is that the Fifth Circuit, though it does not have the final say, often decides what US policy should be for months at a time. And that’s assuming that the Supreme Court actually reverses the Fifth Circuit — sometimes the Fifth Circuit’s most legally dubious decisions are embraced by a Supreme Court dominated by Republican appointees.

If the Fifth Circuit behaves this badly when powerful litigants are before them, imagine what it is like for the powerless

One of the few good things that can be said about the Fifth Circuit is that it does not have the last word about what the law says. When its judges strike down a federal law, or attempt to destroy an entire federal agency, or declare a national policy unconstitutional, the Supreme Court almost always steps up to hear that case. And the justices do frequently reverse the Fifth Circuit’s most outlandish decisions — even if they take their sweet time before they do so.

But the Supreme Court only hears a tiny percentage of the cases decided by federal appeals courts, and it almost never hears cases brought by extraordinarily vulnerable litigants like Trent Taylor. Indeed, it hears these cases so infrequently that, when the Court decided to intervene on Taylor’s behalf, Justice Samuel Alito wrote a brief opinion complaining that Taylor’s case “which turns entirely on an interpretation of the record in one particular case, is a quintessential example of the kind that we almost never review.”

The Fifth Circuit hears a steady diet of ordinary immigration cases, which will often decide whether an individual immigrant can remain with their family in the United States or whether they must be deported to a nation they may barely know, or where they may fear for their physical safety. These cases are now heard by judges like Andrew Oldham, Trump’s sixth appointment to the Fifth Circuit, who spent much of his time both on and off the bench seeking to make federal immigration policies harsher to immigrants.

Similarly, the court hears a steady diet of employment discrimination cases. These cases are heard by judges like Edith Jones, who dissented in a 1989 case ruling in favor of Susan Waltman, a woman who experienced the kind of sexual harassment that would make any normal person’s skin crawl:

During the summer of 1984, an IPCO employee told a truck driver that Waltman was a whore and that she would get hurt if she did not keep her mouth shut. Later, in the Fall of 1984, several other incidents occurred. A Brown and Root employee, who was working at the mill, grabbed Waltman’s arms while she was carrying a vial of hot liquid; another Brown and Root worker then stuck his tongue in her ear. In a separate incident, an IPCO employee told Waltman he would cut off her breast and shove it down her throat. The same employee later dangled Waltman over a stairwell, more than thirty feet from the floor. In November 1984, one employee pinched Waltman’s breasts. In another incident, a co-worker grabbed Waltman’s thigh.

Jones claimed that Waltman’s employer “did not have actual or constructive notice that Waltman was subjected to a pervasively abusive and hostile work environment,” but Waltman complained multiple times to her supervisors, met with senior managers about the harassment she faced, and announced her intention to resign after a shift meeting where her coworkers made comments that “women provoke sexual harassment by wearing tight jeans” in front of her supervisor.

And then, after determining that these conditions do not amount to actionable sexual harassment, Jones spent the next 33 years hearing other cases brought by workers alleging employment discrimination.

The Fifth Circuit has created a void in the law, where judges ignore horrific violations in between writing opinions claiming that entire federal agencies are unconstitutional. And, barring legislation adding additional seats to the court, things are unlikely to get better anytime soon. Currently, Republican appointees hold 12 of the 17 active judgeships on this benighted court — and nearly all of them are ideologically similar to Jones.

That said, there are reforms that Congress or the Supreme Court could implement, which would diminish both the Fifth Circuit’s power and the power of litigants to channel political lawsuits to highly ideological judges. Congress, for example, may strip the Fifth Circuit of its jurisdiction over certain cases, or require certain suits to be filed in a federal court that is not located in the Fifth Circuit. It could also add seats to the court, which would then be filled by President Biden.

A less radical reform, proposed by former Fifth Circuit Judge Gregg Costa, would prevent litigants like the Texas AG’s office from handpicking judges who are likely to rule in their favor — and whose decisions are equally likely to be affirmed by the Fifth Circuit. Costa proposed having all lawsuits seeking a nationwide injunction against a federal law or policy be heard by three-judge panels, rather than a single judge chosen by the plaintiff. These panels’ decisions would then appeal directly to the Supreme Court, bypassing the Fifth Circuit (although a single Fifth Circuit judge might sit on some of these panels).

Realistically, however, systemic reforms to the problem of judge-shopping — and to the problem of a lawless court of appeals — are unlikely to happen anytime soon. The House of Representatives will soon be controlled by Republicans, who are unlikely to support legislation that reduces the power of their partisan allies on the bench. And the Supreme Court has six justices appointed by Republican presidents.

And so the Fifth Circuit will continue to hand down its decrees, confident that no one with the power to stop them is likely to do so.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

She Just Had a Baby. Soon, She'll Start 7th Grade.

Ashley just had a baby. She’s sitting on the couch in a relative’s apartment in Clarksdale, Miss., wearing camo-print leggings and fiddling with the plastic hospital bracelets still on her wrists. It’s August and pushing 90 degrees, which means the brown patterned curtains are drawn, the air conditioner is on high, and the room feels like a hiding place. Peanut, the baby boy she delivered two days earlier, is asleep in a car seat at her feet, dressed in a little blue outfit. Ashley is surrounded by family, but nobody is smiling. One relative silently eats lunch in the kitchen, her two siblings stare glumly at their phones, and her mother, Regina, watches from across the room. Ashley was discharged from the hospital only hours ago, but there are no baby presents or toys in the room, no visible diapers or ointments or bottles. Almost nobody knows that Peanut exists, because almost nobody knew that Ashley was pregnant. She is 13 years old. Soon she’ll start seventh grade.

In the fall of 2022, Ashley was raped by a stranger in the yard outside her home, her mother says. For weeks, she didn’t tell anybody what happened, not even her mom. But Regina knew something was wrong. Ashley used to love going outside to make dances for her TikTok, but suddenly she refused to leave her bedroom. When she turned 13 that November, she wasn't in the mood to celebrate. “She just said, ‘It hurts,’” Regina remembers. “She was crying in her room. I asked her what was wrong, and she said she didn’t want to tell me.” (To protect the privacy of a juvenile rape survivor, TIME is using pseudonyms to refer to Ashley and Regina; Peanut is the baby’s nickname.)

The signs were obvious only in retrospect. Ashley started feeling sick to her stomach; Regina thought it was related to her diet. At one point, Regina even asked Ashley if she was pregnant, and Ashley said nothing. Regina hadn’t yet explained to her daughter how a baby is made, because she didn’t think Ashley was old enough to understand. “They need to be kids,” Regina says. She doesn’t think Ashley even realized that what happened to her could lead to a pregnancy.

On Jan. 11, Ashley began throwing up so much that Regina took her to the emergency room at Northwest Regional Medical Center in Clarksdale. When her bloodwork came back, the hospital called the police. One nurse came in and asked Ashley, “What have you been doing?” Regina recalls. That’s when they found out Ashley was pregnant. “I broke down,” Regina says.

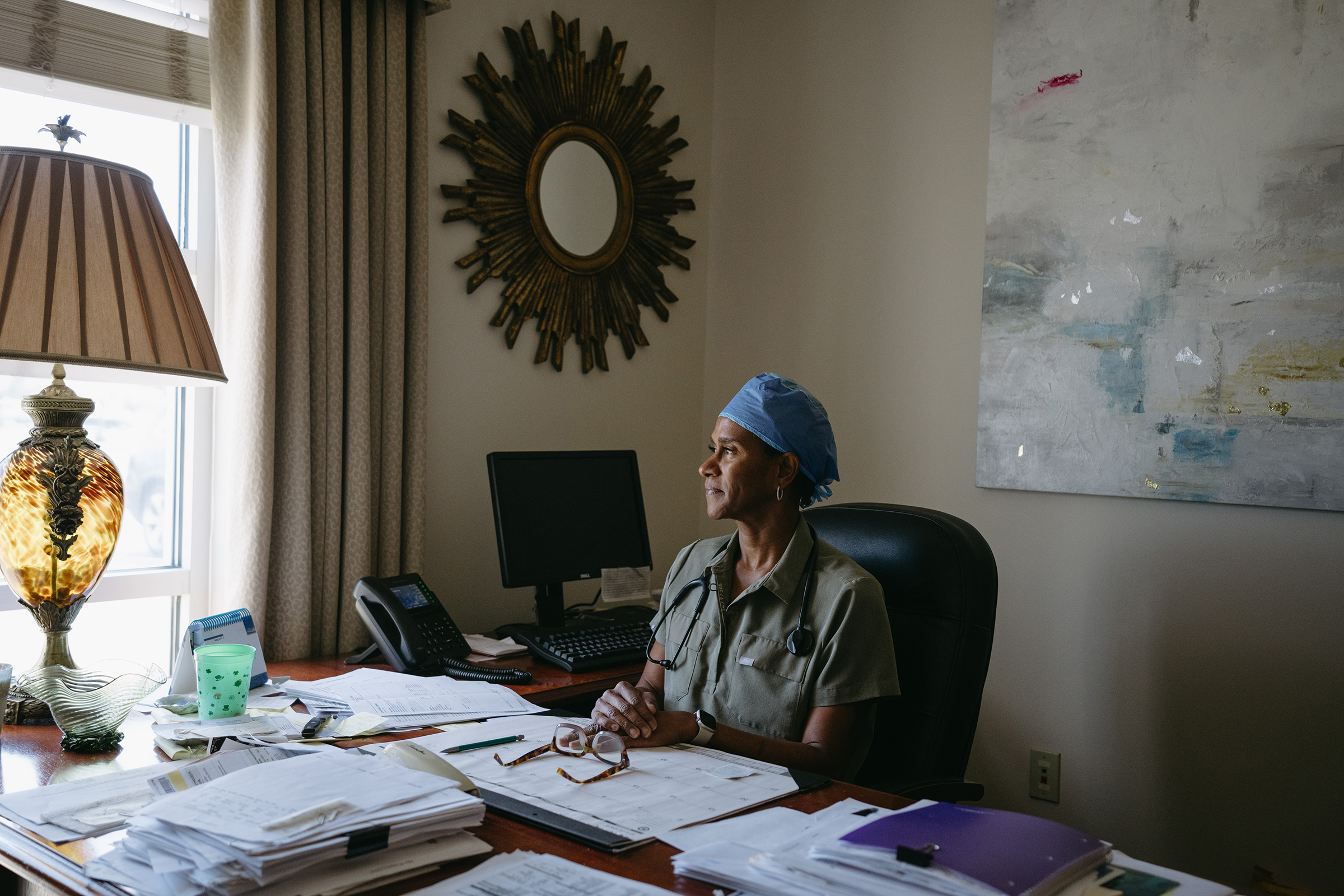

Dr. Erica Balthrop was the ob-gyn on call that day. Balthrop is an assured, muscular woman with close-cropped cornrows and a tattoo of a feather running down her arm. She ordered an ultrasound, and determined Ashley was 10 or 11 weeks along. “It was surreal for her,” Balthrop recalls. "She just had no clue.” The doctor could not get Ashley to answer any questions, or to speak at all. “She would not open her mouth.” (Balthrop spoke about her patient's medical history with Regina's permission.)

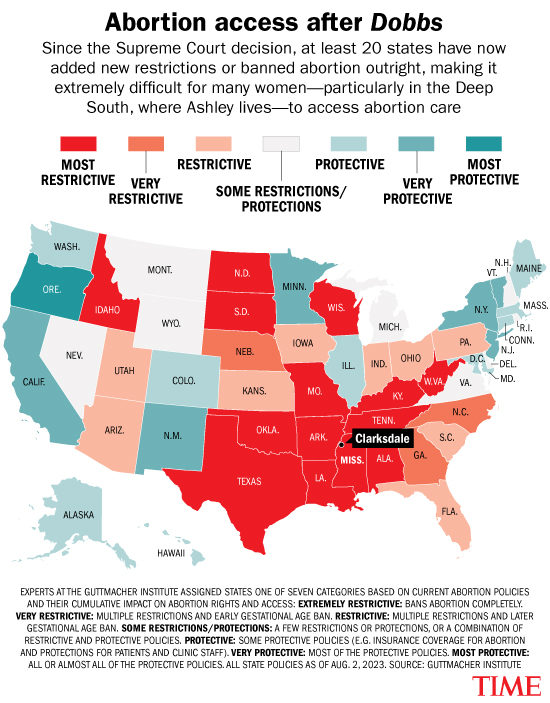

At their second visit, about a week later, Regina tentatively asked Balthrop if there was any way to terminate Ashley’s pregnancy. Seven months earlier, Balthrop could have directed Ashley to abortion clinics in Memphis, 90 minutes north, or in Jackson, Miss., two and a half hours south. But today, Ashley lives in the heart of abortion-ban America. In 2018, Republican lawmakers in Mississippi enacted a ban on most abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy. The law was blocked by a federal judge, who ruled that it violated the abortion protections guaranteed by Roe v. Wade. The Supreme Court felt differently. In their June 2022 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the Supreme Court overturned the constitutional right to abortion that had existed for nearly half a century. Within weeks, Mississippi and every state that borders it banned abortion in almost all circumstances.

Balthrop told Regina that the closest abortion provider for Ashley would be in Chicago. At first, Regina thought she and Ashley could drive there. But it’s a nine-hour trip, and Regina would have to take off work. She’d have to pay for gas, food, and a place to stay for a couple of nights, not to mention the cost of the abortion itself. “I don’t have the funds for all this,” she says.

So Ashley did what girls with no other options do: she did nothing.

Clarksdale is in the Mississippi Delta, a vast stretch of flat, fertile land in the northwest corner of the state, between the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers. The people who live in the Delta are overwhelmingly Black. The poverty rate is high. The region is an epicenter of America’s ongoing Black maternal-health crisis. Mississippi has the second-highest maternal-mortality rate in the country, with 43 deaths per 100,00 live births, and the Delta has among the worst maternal-healthcare outcomes in the state. Black women in Mississippi are four times as likely to die from pregnancy-related complications as white women.

Mississippi’s abortion ban is expected to result in thousands of additional births, often to low-income, high-risk mothers. Dr. Daniel Edney, Mississippi’s top health official, tells TIME his department is “actively preparing” for roughly 4,000 additional live births this year alone. Edney says improving maternal-health outcomes is the “No. 1 priority” for the Mississippi health department, which has invested $2 million into its Healthy Moms, Healthy Babies program to provide extra support for new mothers. “There is a sense of following through, and not just as a predominantly pro-life state,” says Edney. “We don’t just care about life in utero. We care about life, period, and that includes the mother’s life and the baby’s life.”

Mississippi’s abortion ban contains narrow exceptions, including for rape victims and to save the life of the mother. As Ashley's case shows, these exceptions are largely theoretical. Even if a victim files a police report, there appears to be no clear process for granting an exception. (The state Attorney General’s office did not return TIME’s repeated requests to clarify the process for granting exceptions; the Mississippi Board of Medical Licensure and the Mississippi State Medical Association did not reply to TIME’s requests for explanation.) And, of course, there are no abortion providers left in the state. In January, the New York Times reported that since Mississippi's abortion law went into effect, only two exceptions had been made. Even if the process for obtaining one were clear, it wouldn’t have helped Ashley. Regina didn’t know that Mississippi’s abortion ban had an exception for rape.

Even before Dobbs, it was perilous to become a mother in rural Mississippi. More than half the counties in the state can be classified as maternity-care deserts, according to a 2023 report from the March of Dimes, meaning there are no birthing facilities or obstetric providers. More than 24% of women in Mississippi have no birthing hospital within a 30-minute drive, compared to the national average of roughly 10%. According to Edney, there are just nine ob-gyns serving a region larger than the state of Delaware. Every time another ob-gyn retires, Balthrop gets an influx of new patients. “These patients are having to drive further to get the same care, then they're having to wait longer,” Balthrop says.

Those backups can have cascading effects. Balthrop recalls one woman who had to wait four weeks to get an appointment. "That’s unacceptable, because you don't know if she’s high risk or not until she sees you," the doctor says says. Her patient "didn’t know she was pregnant. Now the time has lapsed so much that she can’t drive anyplace to terminate even if she chose to."

Early data suggests the Dobbs decision will make this problem worse. Younger doctors and medical students say they don't want to move to states with abortion restrictions. When Emory University researcher Ariana Traub surveyed almost 500 third- and fourth-year medical students in 2022, close to 80% said that abortion laws influenced where they planned to apply to residency. Nearly 60% said they were unlikely to apply to any residency programs in states with abortion restrictions. Traub had assumed that abortion would be most important to students studying obstetrics, but was surprised to find that three-quarters of students across all medical specialties said that Dobbs was affecting their residency decisions.

“People often forget that doctors are people and patients too,” Traub says. “And residency is often the time when people are in their mid-30s and thinking of starting a family.” Traub found that medical students weren’t just reluctant to practice in states with abortion bans. They didn’t want to become pregnant there, either.

And so Dobbs has compounded America's maternal-health crisis: more women are delivering more babies, in areas where there are already not enough doctors to care for them, while abortion bans are making it more difficult to recruit qualified providers to the regions that need them most. “People always ask me: ‘Why do you choose to stay there?’” says Balthrop, who has worked in the Delta for more than 20 years. “I feel like I have no choice at this point."

The weeks went on, and Ashley entered her second trimester. She wore bigger clothes to hide her bump, until she was so big that Regina took her out of school. They told everyone Ashley needed surgery for a bad ulcer. “We’ve been keeping it quiet, because people judge wrong when they don’t know what’s going on,” Regina says. She’s been trying to keep Ashley away from “nosy people.” For months, Ashley spent most of the day alone, finishing up sixth grade on her laptop. The family still has no plans to tell anybody about the pregnancy. “It’s going to be a little private matter here,” Regina says.

Ashley has ADHD and trouble focusing, and has an Individualized Education Program at school. She had never talked much, but after the rape she went from shy to almost mute. Regina thinks she may have been too traumatized to speak. At first, Regina couldn’t even get Ashley to tell her about the rape at all.

In an interview in a side bedroom, while Ashley watched TV with Peanut in another room, Regina recounted the details of her daughter’s sexual assault, as she understands them. It was a weekend in the fall, shortly after lunchtime, and Ashley, then 12, had been outside their home making TikToks while her uncle and sibling were inside. A man came down the street and into the front yard, grabbed Ashley, and covered her mouth, Regina says. He pulled her around to the side of the house and raped her. Ashley told Regina that her assailant was an adult, and that she didn’t know him. Nobody else witnessed the assault.

Shortly after finding out Ashley was pregnant, Regina filed a complaint with the Clarksdale Police Department. The department's assistant chief of police, Vincent Ramirez, confirmed to TIME that a police report had been filed in the matter, but refused to share the document because it involved a minor.

Regina says that another family member believed they had identified the rapist through social-media sleuthing. The family says they flagged the man they suspected to the police, but the investigation seemed to go nowhere. Ramirez declined to comment on an ongoing investigation, but an investigator in the department confirmed to TIME that an arrest has not yet been made. With their investigation still incomplete, police have not yet publicly confirmed that they believe Ashley’s pregnancy resulted from sexual assault.

Regina felt the police weren’t taking the case seriously. She says she was told that in order to move the investigation forward, the police needed DNA from the baby after its birth. Experts say this is not unusual. Although it is technically possible to obtain DNA from a fetus, police are often reluctant to initiate an invasive procedure on a pregnant victim, says Phillip Danielson, a professor of forensic genetics at the University of Denver. They typically test DNA only on fetal remains after an abortion, or after a baby is born, he says.

But almost three days after Peanut was born, the police still hadn’t picked up the DNA sample; it was only after inquiries from TIME that officers finally arrived to collect it. Asked at the Clarksdale police station why it had taken so long after Peanut's birth for crucial evidence to be collected, Ramirez shrugged. “It’s a pretty high priority, as a juvenile,” he says. “Sometimes they slip a little bit because we’ve got a lot going on, but then they come back to it.”

Ashley doesn’t say much when asked how it felt to learn she was pregnant. Her mouth twists into a shy grimace, and she looks away. “Not good,” she says after a long pause. “Not happy.”

Regina’s own feelings about abortion became more complicated as the pregnancy progressed. She got pregnant with her first daughter at 17, and was a mother at 18. “I was a teen,” says Regina, now 33. “But I wasn’t as young as her.”

Regina had considered abortion during one of her own pregnancies. But her grandmother admonished her, “Your mama didn’t abort you.” Now Regina felt caught between her family’s general disapproval of abortion and the realization that her 13-year-old daughter was pregnant as the result of a rape. “I wish she had just told me when it happened. We could have gotten Plan B or something,” Regina says, referring to the emergency contraceptive often known as the “morning-after pill.” “That would have been that.”

Balthrop often sees this kind of ambivalence. Clarksdale is in the heart of the Bible Belt, and many of her patients are Black women from religious families. Even if they want to terminate their pregnancies, Balthrop says, many of them ultimately decide not to go through with it. Since the Dobbs decision, however, Balthrop has seen an increase in “incomplete abortions,” which is when the pregnancy has been terminated but the uterus hasn’t been fully emptied. Medication abortions— abortions managed with pills, which are increasingly available online—are overwhelmingly safe, but occasionally can have minor complications when the pills are not taken exactly as directed. “They're having complications after—not serious, but they'll come in with significant bleeding, and then we still have to finish the process,” Balthrop says, explaining that they sometimes have to evacuate dead fetal tissue.

According to Balthrop, Ashley didn’t have complications during her pregnancy. But she didn’t start speaking more until she felt the baby move, around her sixth month. “That’s when it hit home,” Balthrop says. “She’d complain about little aches and pains that she had never had before. That’s when her mom would come in and say, ‘She asked me this question,’ and the three of us would sit and talk about it.”

How did Ashley feel in anticipation of becoming a mother? “Nervous,” is all she will say. Toward the end of the pregnancy, she was terrified of going into labor, Balthrop recalls. Most of her questions were about pushing, and delivery, and how painful it would be. She was focused on “the delivery process itself,” Balthrop says. “Not, ‘What am I going to do when I take this baby home?’”

The Clarksdale Woman’s Clinic, where Balthrop practices, is across the street from the emergency room at Northwest Regional Medical Center, where Ashley first learned she was pregnant. The clinic is large and welcoming, with comfortable chairs and paintings of flowers on the walls. The staff is kind and efficient, the space is clean, and it helps that the three ob-gyns on staff are Black, since most of the patients are Black women. The clinic’s strong reputation attracts patients from an hour away in all directions. It is a lifeline in a vast region with few other maternity health options.

Even for healthy patients, it can be dangerous to be pregnant in such a rural area. “We have patients who walk to our clinic. They don't have transportation,” says Casey Shoun, an administrative assistant at Clarksdale Woman’s. Some can get Medicaid transportation, but it’s notoriously unreliable. The trip can be hard even for local residents: the roads leading to the clinic don’t have good sidewalks, and temperatures in the Delta regularly reach 100 degrees in the summer.

Shoun says the clinic gets patients who are six months pregnant by the time they have their first prenatal appointment. “We've had patients who go to the hospital, and they've already delivered,” Shoun says. Balthrop recalls one woman who went into labor about seven weeks early, and had to drive 45 minutes to get to the hospital. She was too late. “By the time she got here, the baby had passed already,” Balthrop says.

Clarksdale Woman's is equipped to handle routine appointments for a healthy pregnancy like Ashley’s. But a pregnant woman with any complication at all—from deep-vein thrombosis to diabetes, preeclampsia to advanced maternal age—will have to make a three-hour round trip drive to Memphis to see the closest maternal-fetal-medicine specialist. The most vulnerable patients are often the ones who have to travel the farthest for pregnancy care.

One morning in August, as the clinic filled, Balthrop allowed TIME to interview consenting patients in the waiting room and parking lot. One of them was Mikashia Hardiman, who is 18 years old and pregnant with her first child. Hardiman had just had her 20-week anatomy scan, and learned that she has a shortened cervix, which means her mother now has to drive her to Memphis to see a specialist.

Jessica Ray, 36, was 13 weeks pregnant with her third child. Three years ago, when she suddenly went into labor with her second child at 33 weeks, she drove herself 45 minutes to the hospital and delivered less than half an hour after she arrived. Ray knows the travel ordeals ahead of her: because she had preeclampsia with her first two pregnancies, she’ll have to go see the specialist in Memphis each month. “You have to take off work and make sure somebody's getting your kids,” Ray says.

Balthrop, who has three kids of her own, has long considered moving to a different region with a better education system. "I feel like I can’t," she says. "I would be letting so many people down."

But the clinic is under serious financial strain. Between overhead, malpractice insurance, the increasing costs of goods and services, and decreasing insurance reimbursements, Balthrop and her colleagues can barely afford to keep Clarksdale Woman's open. They’re considering selling the practice to a hospital 30 miles away. If that happened, Balthrop says, babies would no longer be delivered in Clarksdale, a city of less than 15,000. Some of her patients would have to leave the Delta—possibly driving an hour or more—to get even the most basic maternity care.

For the patients who already struggle to make it to Clarksdale, that would spell disaster. "They just wouldn't get care until they show up for delivery at the hospital,” says Shoun, the administrative assistant. “Imagine if we weren't here. Where would they go?"

Ashley started feeling contractions on a Saturday afternoon when she was 39 weeks pregnant. She called Regina, who came home from work, and together they started timing them. They arrived at the hospital around 8 p.m. that night. An exam revealed Ashley was already six centimeters dilated. Her water broke soon after, and she got an epidural. She delivered Peanut within five hours. Ashley describes the birth in one word: “Painful.”

For Regina, the arrival of her first grandchild has not eased the pain of watching what her daughter has endured. “This situation hurts the most because it was an innocent child doing what children do, playing outside, and it was my child,” Regina says. “It still hurts, and is going to always hurt.”

Ashley doesn’t know anybody else who has a baby. She doesn’t want her three friends at school to find out that she has one now. Regina is working on an arrangement with the school so Ashley can start seventh grade from home until she’s ready to go back in person. Relatives will watch Peanut while Regina is at work. Is there anything about motherhood that Ashley is excited about? She twists her mouth, shrugs, and says nothing. Is there anything Ashley wants to say to other girls? “Be careful when you go outside,” she says. “And stay safe.”

There is only one moment when Ashley smiles a little, and it’s when she describes the nurses she met in the doctors’ office and delivery room. One of them, she remembers, was “nice” and “cool.” She has decided that when she grows up, she wants to be a nurse too. “To help people,” she says. For a second, she looks like any other soon-to-be seventh grader sharing her childhood dream. Then Peanut stirs in his car seat. Regina says he needs to be fed. Ashley’s face goes blank again. She is a mother now.

No comments:

Post a Comment