~~ newestbeginning ~~

The 150 year-old law conservatives are banking on to ban abortion

The Comstock Act was passed by Congress in 1873 during a decades-long crusade against what religious conservatives considered “obscene.” A century and a half later, conservatives are using the 19th century federal law to target abortion across the country. They’ve invoked Comstock in the Texas mifepristone lawsuit; it’s being used in attempts to allow local governments to ban abortion in spite of state law—it’s even cited in threats against pharmacies to prevent them from dispensing abortion medication.

Legal and abortion rights experts expect this is just the beginning of how conservatives plan to use this 150-year old legislation to ban abortion across the nation. Which means, we need to understand what Comstock is all about.

To help us explain the history of the law and how it’s being weaponized today, Abortion, Every Day went to law professors Sonia Suter and Naomi Cahn for help. Here’s what they say you need to know:

History of the Comstock Act

The Comstock Act (officially titled “An Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use”) was enacted in 1873. The law was named after Anthony Comstock, one of the most zealous moral evangelists and anti-vice crusaders of his time. Comstock served in the Union army before working as a porter and salesman in New York City, and was appalled by the “sin and wickedness” he observed in those worlds—including the copious consumption of pornography and alcohol by his fellow soldiers, as well as the prevalence of contraception, prostitution, and pornography in the city, particularly among the poor.

Within less than a year of the statute’s enactment, Comstock was credited with assistance in the seizure of “130,000 pounds of books, 194,000 pictures and photographs, and 60,300 ‘articles made of rubber for immoral purposes, and used by both sexes.’”

In spite of these successes, Comstock feared existing laws were insufficient to address the “monstrous evil” of obscenity, which motivated him to lobby for a federal law to stamp out sinful behavior. Backed by wealthy donors, Comstock took his impressive collection of pornographic pictures, sex toys and contraceptive materials to Washington, D.C. in 1873, where he displayed them at the Capitol to help galvanize Congress to pass anti-obscenity legislation.

Passed hastily and with little debate, the Comstock Act of 1873 criminalized the use of mail for any “obscene, lewd, or lascivious book, pamphlet, picture, paper, print, or other publication of an indecent character, or any article or thing designed or intended for the prevention of conception or procuring of abortion.” The “first of its kind in the western world,” the Comstock Act imposed fines between $100 and $5,000, “imprisonment at hard labor” between one and ten years, or both.

After the Comstock Act was enacted, more than half of the states passed “Little Comstock laws” that mirrored the federal statute.

Ideology & Misogyny Behind the Comstock Act

The Comstock Act was rooted in ideas about purity and the social good as understood by a particular form of American Protestantism which viewed any sex that was not associated with procreation to be a sin.

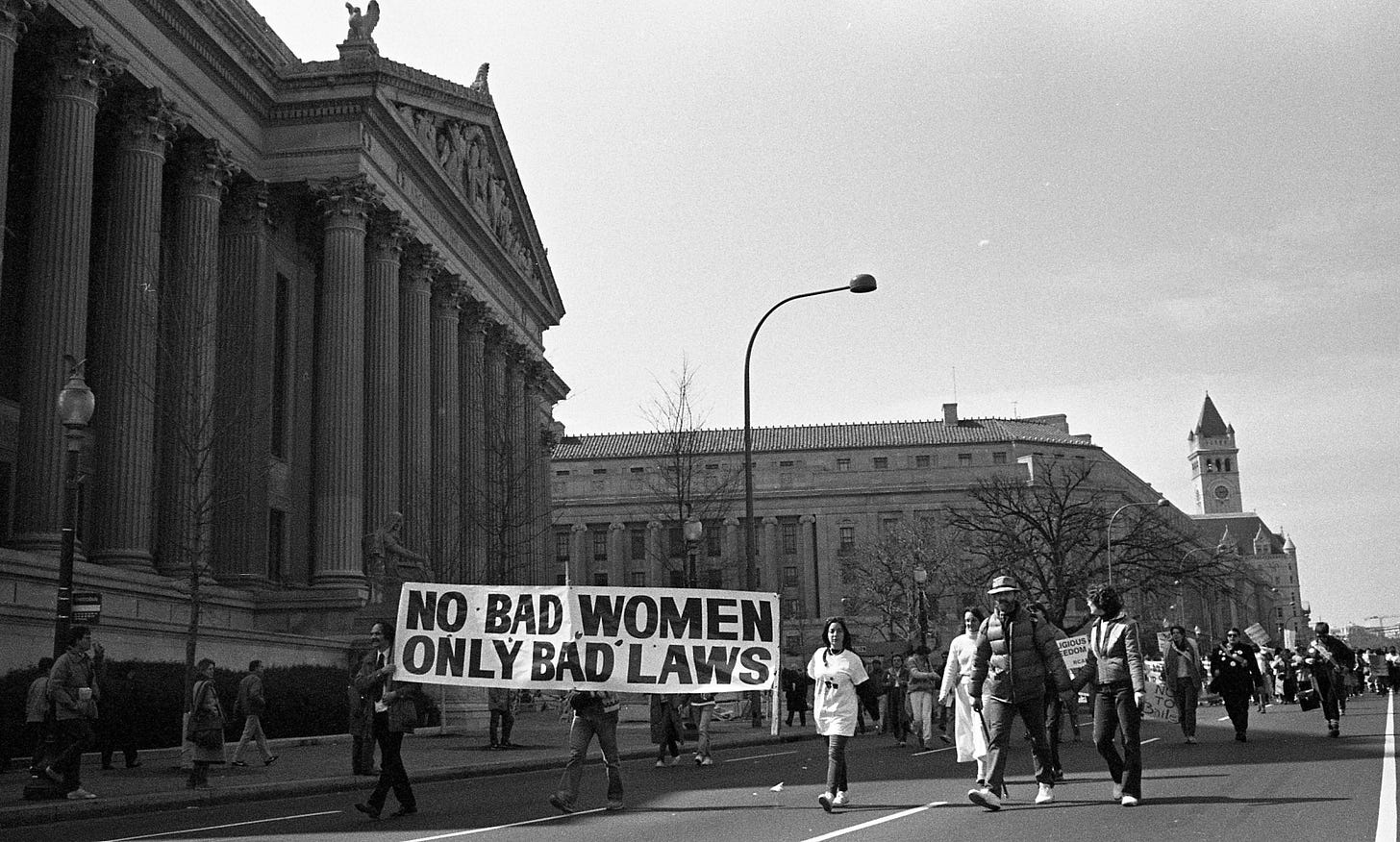

During and after the civil war, socially conservative Christians like Comstock turned to state intervention and state power to enforce sexual morality. These efforts to promote a conservative Christian view of public health were also directed to restoring the “gendered hierarchy” that had existed before and been undermined by the war. Laws like the Comstock Act embody a stunted conception of the role of women. In the words of Yale Law School Professor Priscilla Smith, the statute is “rooted in archaic views of women’s sexual expression and their subservient role in the family.” It is ultimately “designed to control women’s sexual activity.”

In her work to make birth control available, Margaret Sanger challenged the Comstock Act and “Little Comstock laws” in various ways. For example, she published two articles in the New York Call entitled, “What Every Mother Should Know” and “What Every Girl Should Know.” Although the pieces were about venereal disease, and not contraception, Comstock—special agent to the Post Office—prohibited the mailing of the publication. In the next edition of the New York Call, Sanger responded by posting an empty page with the heading: “What Every Girl Should Know: NOTHING! By Order of the Post Office Department.”

Sanger was also arrested and convicted under New York’s Little Comstock law for the sale and distribution of birth control in 1916. And at the end of his life, Comstock assisted in arresting and then prosecuting Sanger’s husband for distributing her pamphlet on birth control.

The Comstock Act’s Contraception & Abortion History

In 1936, the Second Circuit issued a ruling making clear that physicians could mail and distribute contraceptives and information about them. The court interpreted the Comstock Act to allow “the importation, sale, or carriage by mail of things which might intelligently be employed by conscientious and competent physicians for the purpose of saving life or promoting the well being of their patients.”

Notably, it relied on prior courts’ understanding that the Comstock Act did not apply to articles for producing abortion unless “unlawful,” and it concluded that the “same exception should apply to articles for preventing conception.” The court also noted that when originally introduced in the Senate, the Comstock Bill had an exception for prescriptions by “a physician in good standing, given in good faith,” although, ultimately, the exception was not included in the final version of the law.

In 1965, the Supreme Court’s decision in Griswold v. Connecticut found that a state law banning contraception for married people violated the constitution. This decision was viewed as weakening the Comstock Act. Six years later, Congress repealed the provisions related to contraception. It did retain the provisions related to abortion, however.

Comstock Today

Today, the statute prohibits the use of the mail for any “obscene, lewd, lascivious, indecent, filthy or vile article” as well as any “article, instrument, substance, drug, medicine or thing which is advertised or described in a manner calculated to lead another to use or apply it for producing abortion.”

The statute also prohibits anyone from “knowingly” using any “common carrier” (such as a train or trucking company) to transmit the same items.

It’s important to note that after the Dobbs opinion, the US Postal Service asked the Justice Department whether the abortion pill could be mailed under the Comstock Act. In a carefully-worded 21-page memo, issued in December of 2022, the Justice Department concluded that mailing the abortion pill is legal, so long as the sender “lacks the intent that the recipient of the drugs will use them unlawfully.”

Until Dobbs overturned Roe, the anti-abortion movement was less vehement and overt in pursuing the anti-vice campaigns that led to the Comstock Act. Since Dobbs, however, the Comstock Act has been invoked in several cases and seen by some in the anti-abortion movement as the most promising tactic for implementing a national abortion ban.

Can Conservatives’ Comstock Strategy Be Effective?

The Comstock Act is federal law. Federal law overrides state (and local) law. And depending on who is interpreting the law, it could be used to broadly limit or ban abortion.

Read one way, for example, the Comstock Act could prevent mailing mifepristone to a person’s home—regardless of whether this person lives in a state where abortion is legal.

The impact could potentially be even more far reaching if the statute were understood to prevent the shipment not just of mifepristone, but any other abortion pill, like misoprostol: that would make medication abortions virtually inaccessible across the country—again, even in states that do not ban abortion.

An even broader reading of the Comstock Act, which would interpret “article” used for abortions to include any medical instruments used in performing surgical abortions, could restrict access to all forms of abortion throughout the county, and even the shipping of basic medical instruments used during any aspect of obstetrics or gynecology, including a speculum.

Moreover, it is not just the US Postal Service that would be covered. At the time of the Comstock Act, of course, FedEx and UPS did not exist; UPS was formed in 1907, and FedEx didn’t come into existence until the early 1970s. But the law also prohibits any “express company” from engaging in the same acts. That would cover FedEx and UPS. And the law was expanded in 1909, to cover items in “commercial transport.” It thus also applies to interstate shipping, so trucks or trains transporting supplies that could be used in an abortion (or for a routine gynecological exam) could be impacted.

Comstock Act & the Modern Anti-Abortion Movement

The use of the Comstock Act is very much part of a conscious strategy for the anti-abortion movement. The website for Students for Life displays a statement that the Comstock act “means what it says—abortion-causing items are not to be mailed.”

Jonathan Mitchell, a former Scalia clerk and solicitor general of Texas, has been working with Pastor Mark Lee Dickson, who began the campaign for Sanctuary Cities for the Unborn in 2019, to revive the Comstock Act now that Roe has been overturned. Their ultimate goal is to provoke challenges that ultimately reach the Supreme Court.

In 2018, Mitchell published a law review article describing the strategy Texas later adopted with its SB8 bounty-hunter law, which allows individuals to sue anyone who aids or abets an abortion in Texas. The article also paved the way for the resurrection of the Comstock Act, although it never mentioned it explicitly.

In the piece, Mitchell argues that old laws struck down or enjoined by courts never really die without legislative repeal. Instead, if a future court “overrule[s] the decision that declared the statute unconstitutional,” the statute can be enforced once again, even retroactively.

Mitchell has admitted he was “hoping nobody would say anything about the Comstock laws until Dobbs came out.” Since then, he has referred to the Comstock Act “in every lawsuit and piece of legislation he could generate.” Mitchell and Dickson are banking on the potential of this statute to limit access to abortion nationally. In fact, Mitchell acknowledges the breadth of the law's reach. It could, for example, potentially allow for bans on shipping drugs, like misoprostol, which can be used for an abortion—but also to treat an ulcer.

Where the Comstock Act Is Being Invoked Now

The Comstock Act has been invoked in another mifepristone lawsuit: A manufacturer of the generic version of mifepristone, GenBioPro, is arguing that West Virginia’s abortion ban directly conflicts with FDA’s approval of the medication. GenBioPro asserts that under the Supremacy clause of the U.S. constitution, federal law preempts the state abortion ban. West Virginia argued that even if the state ban did not limit GenBioPro, the Comstock Act made its business illegal.

In a preliminary ruling in May, the federal district court rejected the state’s arguments. It conceded that “the plain language of the statute arguably encompasses GenBioPro's business model, [but] the Comstock Act is currently understood to apply only to use of the mails in an illegal manner.”

The Comstock Act is also at the center of a wrongful death case filed in Texas by a man suing three women for helping his ex-wife access medication abortion. One of the claims, buried several pages into the complaint, is that the manufacturer of mifepristone is jointly liable under the Comstock Act.

The complaint asserts that the Justice Department’s “opinion is not binding on the state judiciary and is not entitled to deference from the state courts.” The plaintiff also argues that “the Texas judiciary interprets statutes according to what they actually say, not according to what the Biden Administration or pro-abortion lawyers want them to say.”

Two other cases related to the Comstock Act that are ongoing in New Mexico:

In January, New Mexico’s Attorney General sued several towns that had passed “Sanctuary Cities for the Unborn” ordinances. These ordinances—passed by 67 cities and two counties, to date—require everyone in their jurisdictions to follow the Comstock Act by prohibiting the use of mail to send or receive “any article or thing designed, adapted, or intended for producing abortion; or any article, instrument, substance, drug, medicine, or thing which is advertised or described in a manner calculated to lead another to use or apply it for producing abortion.”

The second New Mexico lawsuit, filed in April, deals with an ordinance enacted by the city of Eunice—as part of the “Sanctuary Cities for the Unborn campaign”—that requires abortion clinics to comply with the Comstock Act. The city has sued the state of New Mexico, asking a court to “declare” that the Comstock Act outlaws “all shipment and receipt of abortion pills and abortion-related paraphernalia throughout the United States, regardless of” the sender’s intent about how the pills will be used.

In language eerily similar to the Texas wrongful death case, the city claims that the Justice Department’s interpretation “is not binding on the state judiciary and is not entitled to deference from the state courts.” The case is currently stayed, as similar issues are pending before the New Mexico Supreme Court. And New Mexico has enacted legislation that prohibits local governments from enacting abortion bans.

The New Mexico lawsuits involve one state’s approach to the Comstock Act, but this could serve as a model for other municipalities.

What happens if Comstock goes to the Supreme Court?

At this point, the mifepristone case is before the Fifth Circuit. Once that court makes its decision, either side can then appeal to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has the option of deciding whether to review the Fifth Circuit’s opinion.

If it decides to review the case, then the Court would likely have two different issues to consider: first, did the FDA engage in an improper process for approving mifepristone; and second, regardless of the approval process, does the Comstock Act preclude mailing and other forms of transportation for mifepristone.

In our view, the Court is unlikely to decide that the approval process was flawed. That would have the far-reaching effect of overturning a standard approval process that evaluates safety and efficacy, which could undermine the approval of many other drugs and impose significant burdens on the pharmaceutical industry because it could not rely on approval granted decades ago.

Instead, the Court might look to the Comstock Act. Indeed, a decision by the Supreme Court to enforce a law that was passed in 1873 would be consistent with its decision in Dobbs to interpret the nature of abortion rights based on the state of the law in 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified. This route is, however, just as dangerous for the future of medication abortion. If the Supreme Court found that approval of mifepristone was problematic under the Comstock Act, then other drugs that can be used for abortions could potentially be subject to similar restrictions, such as misoprostol, the second drug in the medication abortion regimen.

Naomi Cahn is a professor of law at the University of Virginia. She is an expert in family law, reproductive rights, feminist jurisprudence, and aging and the law.

Sonia Suter is a professor of law at George Washington University. Her scholarship focuses on the intersection of law, medicine, and bioethics, with a particular focus on reproductive rights, emerging reproductive technologies, and ethical and legal issues in genetics.

No comments:

Post a Comment