https://www.readtpa.com/p/blame-capitalism-not-wokeness-agatha-christie?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=2282&post_id=111018096&isFreemail=true&utm_medium=email

~~ recommended by newestbeginning ~~

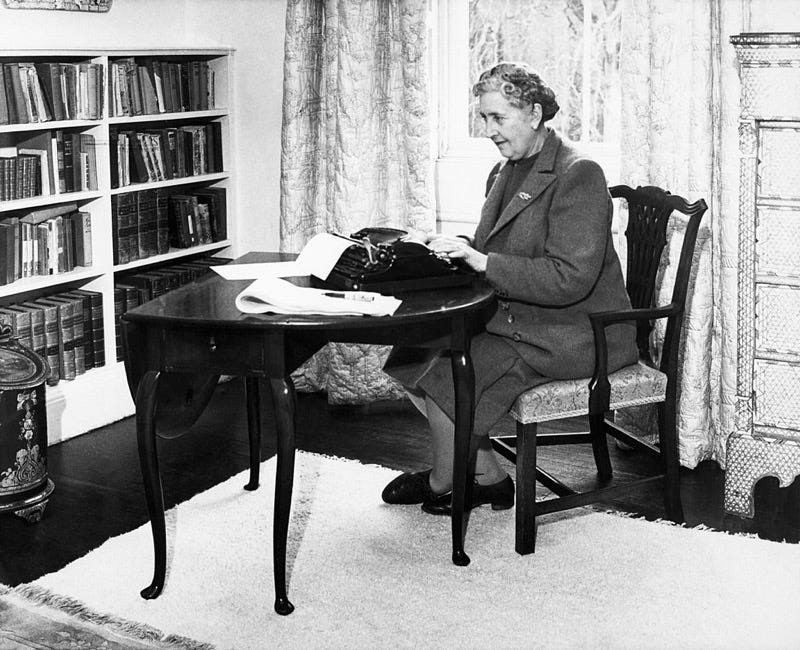

Today, I want to talk about the decision by book publisher HarperCollins to update Agatha Christie's novels. On Saturday, The Telegraph was the first to report on this, writing that the legendary author’s books “have been rewritten for modern sensitivities.”

I am going to be entirely honest with you: I have never read an Agatha Christie novel. That’s okay, though, as I’m sure that 99% of the people you’ll see in the coming days raging about “wokeness run amok” (or something of the sort) will not have read them, either. So, hey, fair is fair.

The Present Age is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I was tempted to take up this topic back in February when people lost their minds over changes being made in new editions of some of children’s author Roald Dahl’s books

. And then there were the updates to Ian Fleming’s “James Bond” novels, which inspired similar outrage and cries of “censorship.” And it’s something I did actually write about back in 2021 when Dr. Seuss Enterprises took six of the Cat in the Hat author’s lesser-known booksout of print. With Agatha Christie’s work in the spotlight, I’m going to bite the bullet and address this topic head-on.Corporations care about one thing: profit.

Does anyone truly believe that Puffin, an imprint of publisher Penguin Publishing Group, made changes to Dahl’s books for the sake of “wokeness” and not, you know, profit? The same company that publishes Jordan Peterson, Ann Coulter, and Christofascist Rod Dreher? That’s the “woke” company? No, of course not. They made changes to these books to try to wring a few extra dollars out of a long-running intellectual property in their possession.

Earlier this month, Zoe Dubno at The Guardian called out these publishers for “using ‘sensitivity readers’ to protect their bottom lines”:

It feels like no coincidence that the Dahl IP was sanitized just before a massive sale to Netflix, nor that Ian Fleming’s estate should, as reported, bring in sensitivity readers to sanitize the James Bond novels in what seems like a last-ditch attempt to save a franchise whose relevance is on the wane and offends contemporary sensibilities. As books become assets, publishers become asset managers trying to future-proof their toxic investments, like BP investing in green energies.

The head honchos of the culture industry say that they’re interested in making sure their titles can be “enjoyed by all today”. If that were true, wouldn’t the most natural thing be to leave books as they are, perhaps with explanatory warnings as introductions, and let them recede from cultural memory, like so many offensive stories already have, making space for new works that deserve to be amplified? Of course, that would be a much riskier financial proposition than pumping out remakes and reprints of evergreen bestsellers.

The argument for revising Dahl was to protect children; but it appears, with Bond, that adult fiction is also getting the sensitivity treatment. Fleming’s estate decided to remove material that could be “considered offensive”, but news reports paint a strange picture of what was deemed acceptable. A visit to a strip club has been deleted, but 007 still muses that all women secretly “love semi-rape”, and Bond is excited by “the sweet tang of rape”. Fleming’s many uses of the N-word are gone, but Bond alludes to Koreans as “rather lower than apes”.

I’ve been thinking about this line for weeks: “As books become assets, publishers become asset managers trying to future-proof their toxic investments, like BP investing in green energies.”

In 2018, Netflix paid up to a reported $1 billion for the film and TV rights to Dahl’s work. In 2021, Netflix dished out another $500 million for Dahl’s catalog outright. The plan? To create “a unique universe across animated and live action films and TV, publishing, games, immersive experiences, live theater, consumer products and more.” Does anyone actually want yet another Willy Wonka movie (this one starring Timothée Chalamet)? Who cares! We’re getting it anyway!

Yes, companies say things they think will sound palatable to audiences when announcing something like edits to materials, and will labor to make it seem as though their actions are guided by a love for the source material and a respect for artistry. That’s corporate public relations at work. The truth, however, has more to do with getting the most bang for their buck, of wringing every last cent out of old IPs. It’s why so much in the world of entertainment is built on sequels and remakes; it’s why seemingly every entertainment company has gone all-in on the idea of multiverses.

But instead of focusing on the actual issue driving changes to books (soulless capitalism), people instead direct their anger at “wokeness.” This is extremely convenient for publishers and IP holders who can’t wait to cash in by putting Matilda in Fortnite or slapping the “Star Wars” name onto a generic video game mid-development.

One other thing should be apparent: the outrage is insincere.

The Telegraph was the first to report on “The rewriting of Roald Dahl” back in February (originally posted on 2/17/23). The Telegraph was the first to report on edits made to Ian Fleming’s work (originally posted on 2/25/23). And yes, the Telegraph is the outlet that broke the news about the changes to Agatha Christie’s work (originally posted on 3/25/23).

In the Telegraph’s reporting on changes to Christie’s works, it even notes that these “new editions” of her novels “are set to be released or have been released since 2020.”

It’s pretty apparent that the Telegraph is now just wading through the works of long-dead authors to see if anything has changed, all to further an “anti-woke” culture war narrative. I suppose it’s less useful to the “anti-woke” political agenda to accurately frame these changes as efforts to smooth the rough edges of old art for the sake of profit, but that’s the truth. This isn’t to say that all changes are bad. For instance, And Then There Were None is one of Christie’s most popular books, and it’s probably for the best that the original title, Ten Little N——s (except with the full word written out), was changed over the years.

There was a really good opinion piece by Matthew Walther (who, I’ll be honest, is usually a bit conservative for my taste, though I read his work anyway) earlier this month at the New York Times. In it, he highlighted the very long history of changes being made to famous texts, and he urged readers to see this issue for what it is (emphasis mine):

The assumption that there is an urgent debate here, one of the utmost importance to the future of culture, society and so on, is politically useful to both sides. But what both sides are really arguing about is not whether it’s ever OK to make posthumous edits, but who gets to make them and why.

In the Dahl case, the changes were proposed by consultants at an organization called Inclusive Minds, which is purported to foster “inclusion, diversity, equality and accessibility in children’s literature.” The edits were permitted by the Roald Dahl Story Company, which manages the author’s copyrights and trademarks, and which was later purchased by Netflix. The profit-seeking corporate context in which the changes were made should raise eyebrows more than the mere fact that people have been mucking around with the texts.

…

In the Dahl case, the edits were not the result of academic deliberation, like the “corrected texts” incorporated into paperback versions of Faulkner novels. Nor were they an admixture of scholarship and financial incentives, like the Hans Walter Gabler edition of Joyce’s “Ulysses” that reset the novel’s copyright status in the 1980s. Here, it was a company treating Dahl’s beloved creations as if they were merely its assets, which they in fact were.

I, for one, do not believe that philistines should be allowed to buy up authors’ estates and convert their works into “Star Wars”-style franchises, as Netflix now seems to be doing, having purchased the Roald Dahl Story Company. In a saner world there would be a sense of curatorial responsibility for these things. “Owning” works of literature, insofar as it should be possible at all, should be comparable to a museum’s ownership of a Caravaggio. Clarify and contextualize, promote and even profit — but do not treat art like you would your controlling interest in a snack foods consortium.

Which is exactly how Dahl’s new owners are behaving. As some constitutionally cynical observers expected, l’affaire Dahl has turned out to be one of those New Coke/Coca-Cola Classic gambits. After a few days of free marketing from the perpetually outraged, it was announced that a 17-volume set of the “classic” versions of Dahl’s books would soon be published. While many culture warriors will be happy to claim this news as a victory, they should ask themselves for whom.

We really don’t have to keep having these same conversations over and over. But if we’re going to do it anyway, we should understand the real reasons billion-dollar corporations do what they do.

No comments:

Post a Comment