https://mronline.org/2023/01/01/a-look-back-on-three-years-of-chinas-anti-covid-19-fight/

~~ recommended by collectivist action ~~

I arrived in Shanghai, 36 hours after leaving São Paulo, a near deportation in South Africa, and a canceled connecting flight. It was March 21, 2020. In the following days, China implemented its mandatory centralized quarantine for all international travelers. Exactly a week later, on March 28, China started its travel ban1 to prevent the spread of a still little-known virus called Covid-19, which was making its way to all corners of the earth.

Nearly three years later, on the coming January 8, 20232, China will officially open its borders, remove the mandatory quarantine and nucleic acid tests for people entering the country, and downgrade the management of Covid-19 from Class A to Class B3. It is not an end of an era; rather, it is a continuation of a rigorous process of confronting a historic and global pandemic, while putting science and the people at its center. It has been an incredible experience to see how the Chinese government and people have taken on this pandemic, while the world has suffered4 6.68 million recorded deaths, with over 650 million people infected. The impact of this virus is one for the history books, the lasting effects to be studied for years to come, and the fight has not yet ended.

The Western mainstream media, however, has been quick to criticize China every step of the way, from the “draconian5” Zero-Covid strategy to the “dystopian6” measures to ensure a safe Winter Olympics games in Beijing, and now to the “nightmare7” of relaxing the country’s Covid-19 requirements. Rhetoric aside, what has the fight against the virus been like in China—characterized by the Zero-Covid strategy—and why are the relaxation measures happening now? It is important to look back at the last three years to understand how we arrived at this point today. Having lived in China throughout the ebbs and flows of the Covid-19 virus, I would categorize the country’s dynamic strategy into four key phases.

Phase 1: Emergency response (December 2019 to May 2020)

Two-and-a-half weeks after I arrived in China, on April 8, the country celebrated the end to the 76-day historic lockdown in Wuhan, where the pandemic first broke out and claimed the lives of 4,512 Chinese people8. It was an emotional and bittersweet victory for the entire country, which had mobilized its people and resources to fight a very deadly and never-before-seen virus.

On December 26, 2019, Dr. Zhang Jixian9, director of the Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine of Hubei Province hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine, saw an elderly couple that had a high fever and a cough—symptoms that characterize the flu. But further examination ruled out influenza A and B, mycoplasma, chlamydia, adenovirus, and SARS. She and her team then quickly determined there was a new virus at play. Three days later, the provincial authorities were alerted, then the Chinese Center for Disease Control (CDC) and by December 31 the WHO was informed10. On New Year’s Day, the CDC officials called11 Dr. Robert Redfield, head of the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, while he was on vacation, to inform him of the severity of their findings.

On January 3, the virus was identified with its genetic sequence which was then shared12 with the world a week later. At this point, there were many unknowns—what the virus was, how it was transmitted, and how it could be stopped. There were no vaccines, while the country—and the world—was unprepared. A strict lockdown of the city of 11 million people began on January 23, and 41,000 medical workers13 were dispatched from across the country to Wuhan. Saving lives and studying this new virus were the main priorities in this phase.

Phase 2: Control and elimination (June 2020 to July 2021)

After Covid-19 had been successfully contained in Wuhan, and throughout the rest of 2020 and 2021, China implemented a Zero-Covid strategy, characterized by extensive measures to track, test, isolate, and treat infected people. The Chinese mainland recorded extremely few deaths14 in this period since the Wuhan outbreak, while successfully containing 11 outbreaks15 of the Delta variant, which is more transmissible and the cause of more serious infections. Meanwhile, the global reported death toll had climbed to over 5.4 million people16 by the end of 2021 with countless millions more infected.

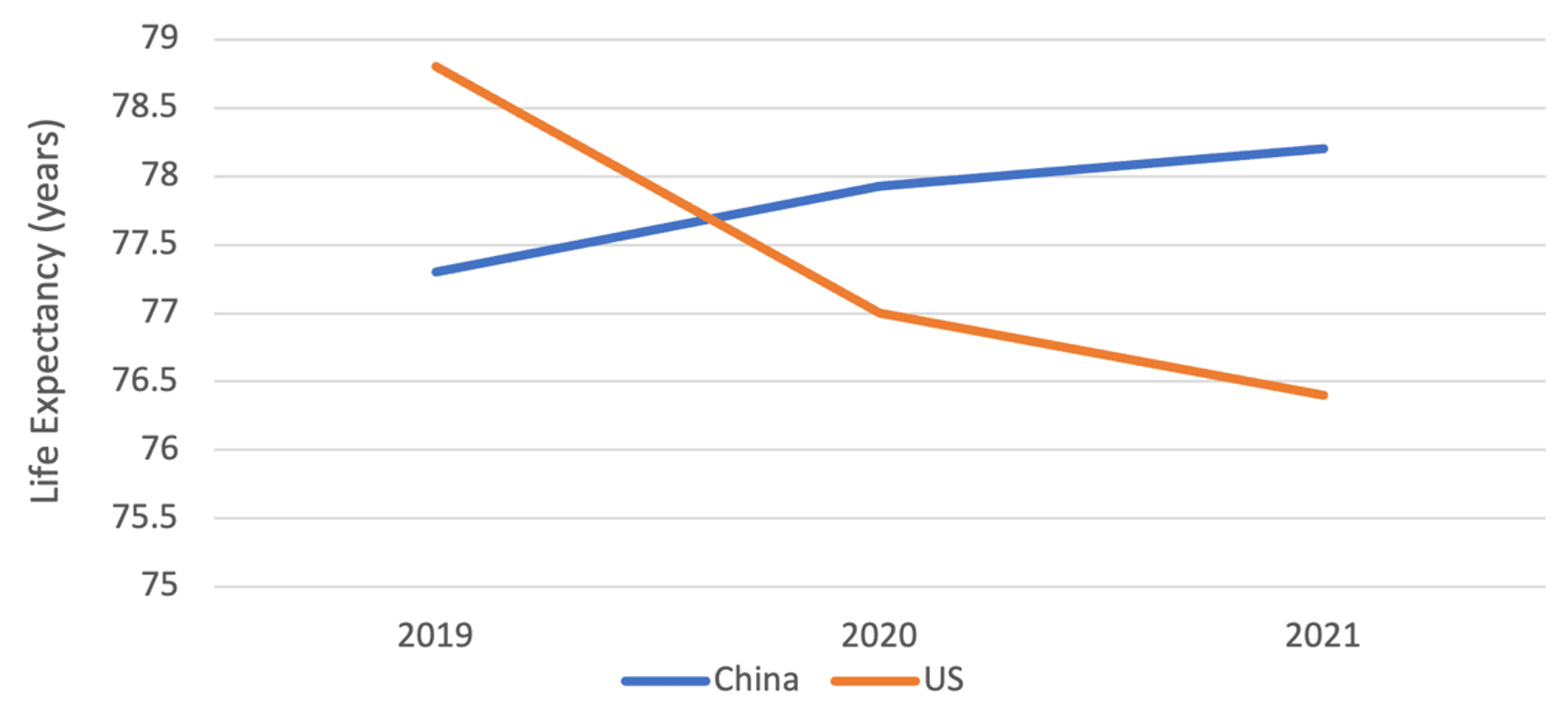

Far from “failing17” as the Western media is claiming now, Zero-Covid worked extremely effectively. Since the pandemic broke, the average life expectancy of Chinese people actually increased from 77.318 to 78.219 years (2019-2021), surpassing the United States for the first time in history (Chart 1). In the U.S., however, the average life span dropped from 78.820 to 76.421 years during that same period, owing in large part to the high number of Covid-related deaths. This is particularly striking when you consider that China was the eleventh22 poorest country in the world in 1949 (measured by per capita PPP GDP) with a life expectancy of only 3623 versus 6824 for the U.S. This means that an average Chinese person’s lifespan more than doubled, whereas in the U.S., the average lifespan only grew by eight years in nearly eight decades.

Chart 1. Life expectancy in China and the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic

The U.S. has recorded 1.1 million deaths due to Covid-19. The cumulative U.S. death rate per one million people is currently 83425 times that of China (3,339 versus 4). In the case of the U.S. and China, the use of “excess-death” numbers—the difference between observed and expected mortality rates—is of little value for analysis purposes as both countries had relatively low numbers of these deaths in the last three years. If China had followed the reckless U.S. path, these figures indicate China would have suffered 4.8 million dead. Even a quick calculation reveals that China’s strategy indeed saved millions of lives.

While it was containing the virus, China was also intensely studying the virus and developing responses, inaugurating26 its first vaccine, Sinopharm, in December 2020, which was subsequently approved27 by the WHO for emergency use on May 7, 2021. By October of that year, according to a Nature study28, Chinese vaccines accounted for nearly half of the 7.3 billion doses delivered globally. Since then, China has approved29 eight vaccines, with 35 others undergoing clinical trials, donated30 328 million doses, pledged31 over US$100 million to the Covax global vaccine distribution program for Global South countries, and proposed32 that vaccines become a global public good.

Phase 3: Adaptation and preparation (August 2021—October 2022)

In August 2021, in response to the spread of the highly transmissible Delta variant, China adopted33 a new strategy called “Dynamic Zero-Covid.” It was designed to balance health, economic, and social needs and to minimize the impact of the epidemic on the economy, society, production, and the people’s everyday life.

There is no one-size-fits-all measure for a country of 1.4 billion people. During this third phase, guided by science, the country experimented with its prevention and implementation practices. Mass testing was developed to high levels of efficiency, in which Guangzhou34’s 18 million inhabitants could be tested a mere three days, while the cost of pooling PCR tests (ten samples per test tube and taking advantage of low infection rates) were reduced to merely 3.5 yuan35 (US$0.50) per person. The country developed a nation-wide digital travel code and city-level “green code” cellphone applications36 to track Covid cases and those who have visited high-risk areas. All the while, the government moved towards more targeted measures to limit the use of large-scale lockdowns. During the Shanghai outbreak, for example, residential communities were classified37 into “lockdown,” “controlled,” or “precautionary” zones based on their risk level to try to minimize the interruption of daily and economic life.

Between January 2020 and mid-April 2022, China had spent38 an estimated US$45.1 billion to provide 11.5 billion free PCR testing for its residents. The costs of this mass testing strategy, however, were also mounting, with estimates reaching 1.8 percent39 of the country’s GDP and putting pressure especially on local government budgets. Despite the economic pressures, rather than “crippling40” China’s economy, the country’s GDP grew nearly four times faster than the U.S. and five times compared to the EU, from the start of the pandemic to Q3 of 2022.41

Despite being the second largest economy, China is still a developing country. The pandemic strained the country’s medical system, which was lacking in several key areas. Accordingly, China used the last three years to begin to fill in those gaps, primarily through increasing its intensive care unit (ICU) capacity. In 2019, China had only 3.6 ICU per 100,000 residents42, which was nine times less than the U.S. with 34.7 units. Since 2019, China increased43 its supply of ICU beds 2.4-fold (57,160 in December 2019 to 138,800 in December 2022). In the same period, ICU doctors and nurses44 increased by one-third and doubled, respectively.

On January 15, 2022, China had its first case of locally transmitted Omicron infection. On April 18, 2022, Shanghai announced45 its first three Covid-related deaths, all unvaccinated elderly people aged over 89 years. At the time of the Shanghai outbreak, while 87 percent46 of the country were already fully vaccinated, that number dropped to only 62 percent47 for the city’s 3.6 million elderly aged over 60, with 38 percent having received booster shots. The country knew that this vulnerable sector of the population had to be protected.

Significant efforts have since been made to increase vaccination of the elderly. The official National Health Commission reported48 that on November 30, 2022, the breakdown of vaccination rates for people aged over 80 years are as follows: 76.6 percent at least one shot, 65.8 percent two shots or more, and 40 percent three or more doses. Despite the lower mortality rates of the Omicron variant, its highly contagious nature posed serious challenges to the country’s existing prevention and control measures, while putting great strains on the economy. Even two doses49 of so-called advanced Western mRNA vaccines like Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine or Moderna’s similar mRNA vaccine provide only about 30 percent protection against symptomatic infection from Omicron for about four months.

Phase 4: Downgrading severity and easing controls (November 2022 to present)

As Omicron began to spread, comparisons50 showed that the risk of death when infected with Omicron BA.2 was less than half that of Delta. One Chinese scientific study51 on mice showed that the new Covid-19 strains had 100 times lower virus load than the original, but was highly transmissible. China knew it needed to adjust its policies with the shifting nature of the virus, but with some important considerations.

On November 11, the central government released its “20 measures”52 to begin to relax its Zero-Covid policies. This included reducing mandatory quarantine time for inbound flights, decreasing isolation times, promoting vaccination of elderly, and eliminating the use of mass testing. For a country of its size, any central government policy takes time and huge organizational capacity to be implemented at the local scale.

The easing created initial confusion, and some people were upset with local community officials for not upholding the central government’s easing measures, frequently aired on Chinese social media platforms. Though there was frustration and exhaustion, it would be a mistake to believe that the downgrading phase was a response to the series of small, coordinated “white paper protests” that occurred after an Urumqi apartment fire that claimed the ten lives on November 24. Not only did the protests occur two weeks after the government began relaxing its Covid measures, but they were also not representative of the Chinese public opinion at large. The government easing also sparked another concern, with many people worried about getting infected. Several Weibo social media users53 expressed anger and criticism of the protesters, seeing them as irresponsible, middle-class youth who wanted their personal liberties at a collective expense. Unlike the blanketing Western media portrayals, Chinese people do not have a singular voice.

On Monday December 26, China announced54 it will downgrade the management of Covid-19 from Class A to Class B of infectious diseases on January 8, 2023. The three main reasons for this change include the fact that Omicron is not as virulent as Delta, a large percentage of the population had been vaccinated, and the country’s health system was better prepared. China uses a three-level system for the classification of infectious diseases, each delimiting specific response measures. Class A, the most dangerous, includes only cholera and the plague. Class B includes SARS, AIDS, and tuberculosis. Class C includes the flu and the mumps. Corresponding to this change, Covid-19 measures will be further relaxed.

Twelve55 main countermeasures were identified for the new Covid-19 policy corresponding to Class B control: 1) Increase vaccination rates; 2) prepare drugs and testing reagents for patients; 3) increase investment in construction of medical resources including ICU beds; 4) shift from mass PCR testing; 5) treat patients according to severity; 6) improve health survey and data, including vaccination status of those aged over 65 years; 7) control vulnerable population institutions, including elder care, hospitals, and schools; 8) strengthen prevention and control for rural areas and for high-risk patients; 9) increase epidemic monitoring, response, and control; 10) promote personal protection and the principle of everyone’s responsibility for their own health; 11) enable information access and education; and 12) optimize international personnel exchanges.

In a press conference56 of the State Council Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism, Dr. Yin Wenwu, Chief Physician of CDC’s Division of Infection Prevention, addressed the consequence of classifying Covid-19 as a Class B, which would reduce the frequency of the publication of data. The new data, which will be released monthly, will include the number of existing hospitalized cases and serious illnesses, including critical illnesses, and the cumulative number of deaths.

As expected, downgrading the severity of the virus’s management would also mean increasing the number of infections and related deaths. However, no single prediction model can be easily applied to China. Existing models for Covid-19 infection and mortality predictions have a wide range of outcomes. Forecast accuracy tends to decrease as prediction times increase, with models showing up to fivefold increase57 in error comparing one-week to 20-week horizons. Even the same Omicron variant has resulted in varied mortality rates in different countries. As of December 21, the U.S. seven-day rolling death rate58 was as high as 437 people, or a rate of 1.29 per million. Meanwhile, Japan had a comparable rate of 2.0 per million and New Zealand 0.85 per million.

Although China has now surpassed the life expectancy of the U.S., it has relatively fewer people 75 years and older than the U.S. (46 percent59 fewer as a percentage of the total population for each country). Omicron has had the impact that a massive 69 percent60 of all Covid-19 deaths in the U.S. in September 2022 were from this age group. The demographic difference in this age group, taken as a stand-alone factor, would imply an over 30 percent reduction in likely death rates for China.

Western media have been quick to use selective stories and photographs to create a broader image of the “chaotic61” situation in China, including alleging very high death rates. China, with a population of over 1.4 billion people, had over 27,00062 deaths per day prior to the Pandemic Using existing Omicron death rates from other countries would infer a possible 6 percent increase in death rates. These would be significant deaths, into the many tens of thousands, but there is no evidence yet provided that supports the millions that the West is speculating.

This downgrading phase is indeed complex and challenging, as doctors are working overtime with increase in cases, some hospitals are in full capacity, fever medicines have faced shortages, and winter-related ailments are adding complications. However, relaxing measures now means that China has used the last three years to try to prepare itself the best that it can by vaccinating the people, studying the virus, building medical infrastructure, training workers, and waiting until a much less deadly strain had emerged. It has also gained hard-earned experience that is essential to managing any future pandemic.

Steps being taken now

Not for lack of vaccines, there are several reasons for the relatively slow vaccination rates for China’s elders. Many of them63 had preconceived notions about vaccines or were worried about complications related to underlying health conditions, while the successful control of the virus disincentivized elders to get vaccinated. Comparatively, in the United States, only 36 percent of people 65 and older have received the updated shot, known as the bivalent booster64, according to data65 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. China, on the other hand, has consistently made efforts to convince, and not coerce, this vulnerable group to get vaccinated.

On November 29, the State Council’s Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism, adjusted the booster vaccination protocol, and required localities66 to extensively survey senior populations and ramp up services and awareness campaigns. Between December 1 and 13, 823,00067 of those over 80 years old received a third vaccine. China has created the world’s first commercially released inhaled vaccine68 for Covid-19: CanSino Biologics’ Convidecia Air, a non-replicated viral vector vaccine. This booster is already gaining popularity69 with the elderly.

Regarding the supply of medicines, some cities had shortages of fever medicines in the first weeks of December as cases increased. Hoarding, price-gouging, and the spike in demand were among the factors that contributed the supply shortage. In response, local governments started to distribute70 Ibuprofen for free, and Beijing residents, for example, can now get Ibuprofen and Paracetamol within an hour. China also passed a regulation71 on online pharmaceutical suppliers, that included penalties up to five million RMB (US$720,000) for pharmacies that increase prices according to speculative behavior. China has72 also made Pfizer’s Paxlovid oral antiviral treatment available.

Due to mass testing during phase three of the anti-pandemic fight, the government was able to obtain accurate data about the virus to inform its responses. As mass testing has been phased out in this current phase, some data precision will inevitably be foregone. However, China’s resilience is demonstrated in its ability to respond to new situations, applying technologies and science to evolve its public health system. For example, in the past two weeks, over ten provincial CDC’s, including in Sichuan, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, have launched surveys73 with hundreds of thousands of participating citizens. This survey data, though limited by sampling methodology, provides an important reference for local and central authorities to monitor the path of the disease, and collect information including on important hospitals, availability of fever drugs, and response capacity of local governments.

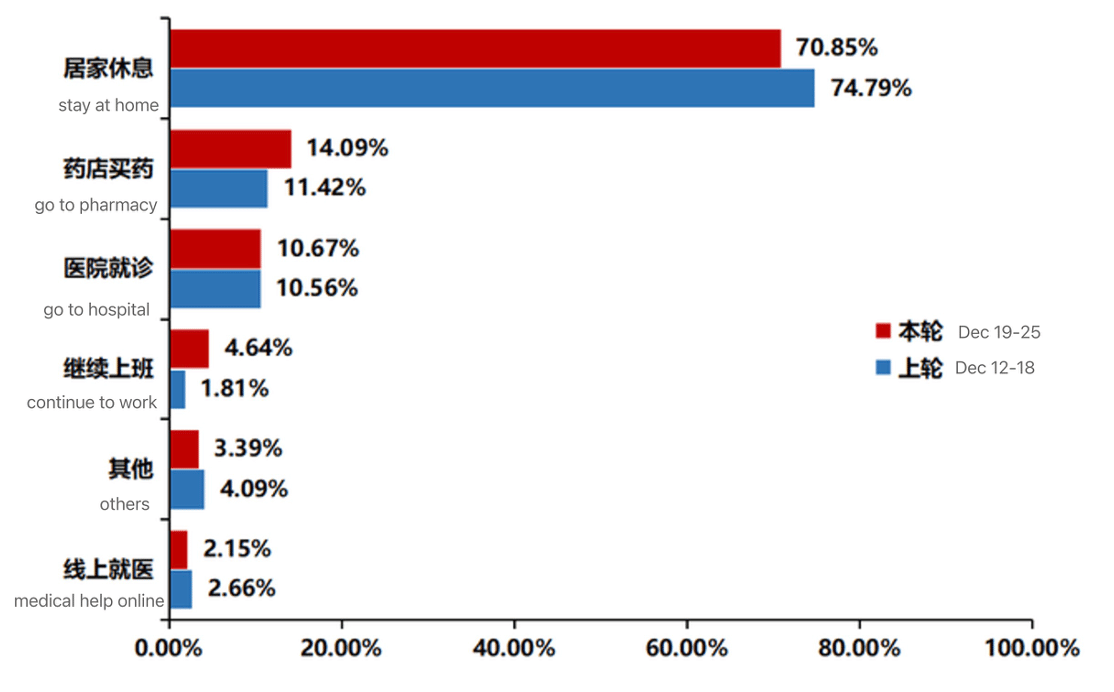

On December 31, Hainan released74 the results of their second online survey (conducted December 19-25) filled in by about 3.4 percent of the province’s population. Below is one of the charts released (Chart 2).

Chart 2. Proportion of infected persons health care seeking behavior in the two rounds of survey population

China’s CDC continues to actively conduct real-time dynamic monitoring on Covid-19. From December 1 to 29, it had completed the whole genetic sequencing of 1,14275 cases through sampling survey. There are seven Omicron subvariants circulating, two of which, BA.5.2 and BF.7, account for more than 80 percent of all cases. BF.7 has greater immune escape ability, a shorter incubation period, and faster transmission. Guangzhou reported76 that 96 percent of people infected and tested had the BA5.2 variant, the symptoms of which are generally considered milder. There has been no reemergence of the Delta variant or other previous strains. However, the U.S. has conveniently used this moment to target visitors from China, requiring them to show negative Covid-19 tests to enter the country. Ironically, it was the U.S. that failed77 to prioritize Covid-19 variant surveillance in 2020.

Several prediction models have been published in the last week, including one by former CDC chief scientist of epidemiology Zeng Guang,78 states that the infection rate in Beijing may have exceeded 80 percent. These models also predict that the second wave is likely to be much milder and point to three factors behind the higher hospitalizations in the city: Beijing’s winter exacerbates respiratory symptoms among the elderly, Beijing is now listed as a moderately aging society (with 20 percent79 of the residents are above 60 years old, and the dominant80 BF.7 subvariant appears more virulent.

The government is paying close attention81 to the availability of medical resources, especially in the rural areas, in anticipation of the week-long spring festival starting January 21. China has increased daily production82 of antigen tests to 110 million units, along with 250,00 oximeters per day, and is prioritizing supply to rural areas. Rapid antigen tests cost as low as US$0.51 each on the e-commerce platform, Pinduoduo. In the rural areas where the medical infrastructure is less developed, the severity of the virus is not as bad as originally feared, according to online accounts83. Barefoot doctors84, a legacy of the Mao-era and sometimes pilloried by those seeking to privatize rural health, have been essential in providing care in rural eras despite having less resources than major city hospitals.

A look back at the last three years shows how difficult the pandemic has been for China and the world, testing the Chinese government’s capacity to confront such an unforeseen public health crisis as well as the people’s patience. In Beijing where I live, however, people are back and bundled in the streets, at work, and on the subways, with traffic and travel recovering. People are anxiously awaiting the spring festival, the most important holiday of the year. As we enter into a new year and a new era of fighting Covid-19—while anticipating the new viruses that will inevitably emerge—the hope is that the world can learn from these hard-earned lessons, act and cooperate using science, not rumors, and embody a spirit of international solidarity, not stigma.85

***** Notes at https://mronline.org/2023/01/01/a-look-back-on-three-years-of-chinas-anti-covid-19-fight/

No comments:

Post a Comment