www.vulture.com/article/octavia-e-butler-profile.html

~~ recommended by collectivist action ~~

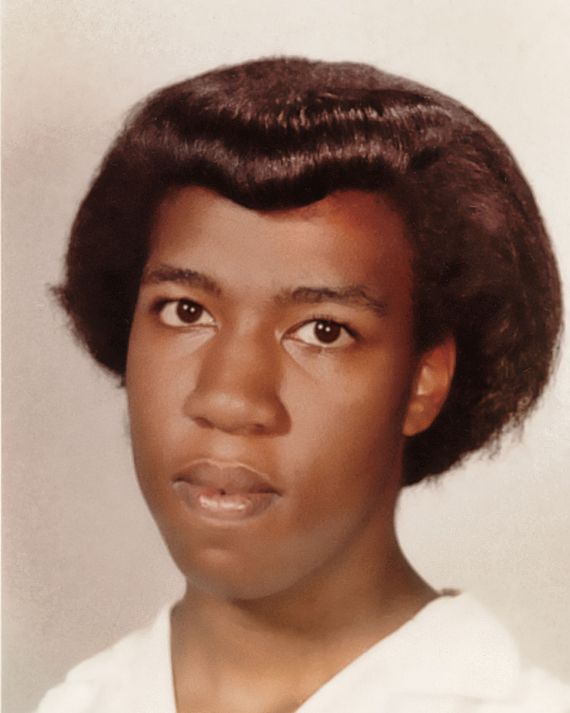

In her family, Butler went by Junie, short for Junior, and in the world, she went by Estelle or Estella to avoid confusion for people looking for her mother. As a girl, she was shy. She broke down in tears when she had to speak in front of the class. Her youth was filled with drudgery and torment. The first time she remembered someone calling her “ugly” was in the first grade — bullying that continued through her adolescence. “I wanted to disappear,” she said. “Instead, I grew six feet tall.” The boys resented her growth spurt, and sometimes she would get mistaken for a friend’s mother or chased out of the women’s bathroom. She was called slurs. It was the only time in her life she really considered suicide.

She kept her own company. In her elementary-school progress reports, one teacher wrote that “she dreams a lot and has poor concentration.” That was true. She did dream a lot, and she began to write her dreams down in a large pink notebook she carried around with her. “I usually had very few friends, and I was lonely,” Butler said. “But when I wrote, I wasn’t.” By the time she was 10, she was writing her own worlds. At first, they were inspired by animals. She loved horses like those in The Black Stallion. When she saw an old pony at a carnival with festering sores swarmed by flies, she realized the sores had come from the other kids kicking the animal to make it go faster. Children’s capacity for cruelty stayed with her. She went home and wrote stories of wild horses that could shape-shift and that “made fools of the men who came to catch them.”

She found a refuge at the Pasadena Public Library, where she leaped into science fiction. She especially liked Theodore Sturgeon, Ursula K. Le Guin, Frank Herbert’s Dune, and Zenna Henderson, whose book Pilgrimage she would buy for her friends to read. She was a comic-book nerd: first DC and then Marvel. When she was 12 years old, she watched Devil Girl From Mars, a black-and-white British science-fiction movie about a female alien commander named Nyah who has mind-control powers, a vaporizing ray gun, and a tight leather outfit with a cape that touches the floor. Butler thought she could come up with a better story than that, so she began to write her own: temporary escape hatches from a life of “boredom, calluses, humiliation, and not enough money,” as she saw it. “I needed my fantasies to shield me from the world.”

When she learned she could make a living doing this, she never let the thought go. Later, she would call it her “positive obsession” and would put it all on the line. Her mother’s youngest sister, who was the first in the family to go to college, became a nurse. Despite her family’s warnings, she did exactly what she wanted to do. That same aunt would tell Butler, “Negroes can’t be writers,” and advise her to get a sensible job as a teacher or civil servant. She could have stability and a nice pension, and if she really wanted to, she could write on the side. “My aunt was too late with it, though,” Butler said. “She had already taught me the only lesson I was willing to learn from her. I did as she had done and ignored what she said.”

Butler would grow up to write and publish a dozen novels and a collection of short stories. She did not believe in talent as much as hard work. She never told an aspiring writer they should give up, rather that they should learn, study, observe, and persist. Persistence was the lesson she received from her mother, her grandmother, and her aunt. In her lifetime, she would become the first published Black female science-fiction writer and be considered one of the forebears of Afrofuturism. “I may never get the chance to do all the things I want to do,” a 17-year-old Butler wrote in her journals, now archived at the Huntington Library in Pasadena. “To write 1 (or more) best sellers, to initiate a new type of writing, to win both the Nobel and the Pulitzer prizes (in reverse order), and to sit my mother down in her own house before she is too old and tired to enjoy it.” The world would catch up to her dreams. In 2020, Parable of the Sower would hit the best-seller list 27 years after its initial publication and 14 years after Butler’s death. After years of imitation, Hollywood has put adaptations of nearly all of her novels into development, beginning with a Kindred show coming to Hulu in December. She is now experiencing a canonization that had only just begun in the last decade of her life.

“I never bought into my invisibility or non-existence as a Black person,” Butler wrote in a journal entry in 1999. “As a female and as an African-American, I wrote myself into the world. I wrote myself into the present, the future, and the past.” For Butler, writing was a way to manifest a person powerful enough to overcome the circumstances of her birth and what she saw as her own personal failings. Her characters were brazen when she felt timid, leaders when she felt she lacked charisma. They were blueprints for her own existence. “I can write about ideal me’s,” she wrote on the cusp of turning 29. “I can write about the women I wish I was or the women I sometimes feel like. I don’t think I’ve ever written about the woman I am though. That is the woman I read and write to get away from. She has become a victim. A victim of her upbringing, a victim of her fears, a victim of her poverty — spiritual and financial. She is a victim of herself. She must climb out of herself and make her fate. How can she do this?”

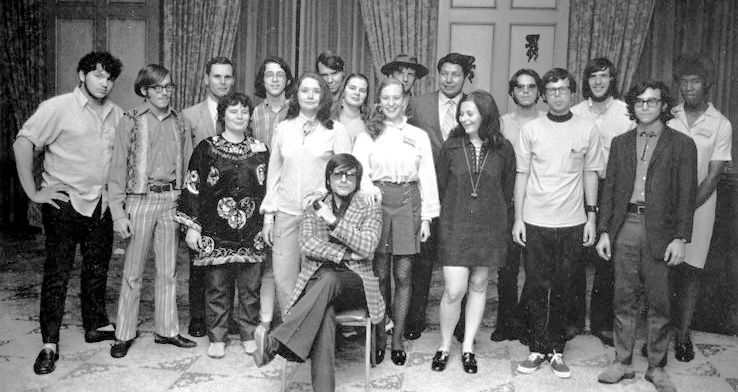

Butler was on the 6 p.m. Greyhound bus in Pittsburgh heading home from the Clarion Workshop for science-fiction writers. She felt proud of the past six weeks. She had just turned 23, and Clarion was the first time she was taken seriously as a writer. After graduating from high school, she had continued to live at home while attending Pasadena City College. She exhausted the creative-writing classes there and the extension classes at UCLA, where a teacher had once asked her, “Can’t you write anything normal?” She got into a screenwriting class at the Open Door Workshop through the Writer’s Guild of America, where she met the writer Harlan Ellison. She knew his work well, particularly his anthology Dangerous Visions, which was part of a literary, more socially minded turn in the genre. He later said she “couldn’t write screenplays for shit” but knew she was talented and encouraged her to go to Clarion, even giving her some money.

Clarion was the farthest Butler had ever been from home and required a three-day cross-country trip to get there. Adjusting was difficult at first. Western Pennsylvania was hot, humid, and lonely. The radio stations stopped playing at eight. When the other students socialized, she wrote letters to her friends and mother — six in the first week. Epistolary writing was a way to unload and unblock herself and, at least at Clarion, to feel less isolated. “Write me and prove that there are still some Negroes somewhere in the world,” she wrote to her mother early on. Ellison did tell her there would be one Black teacher there: Samuel Delany, who at 28 was a literary wunderkind. He’d published nine novels by then, winning the Nebula Award — the field’s highest honor — for Best Novel two years in a row. When Butler saw him for the first time, she told him he looked like a wild man from Borneo. (She probably shouldn’t have said that, she thought later.) When she felt particularly hard on herself, she would write letters to her mother she never sent. “I’m not doing anything,” she wrote. “I’m hiding in this blasted room crying to you. Which is disgusting.” Her mother had forgone dental work so Butler could attend. She wouldn’t complain like that.

Yes, she was still shy. She rarely spoke in class, and when she did, she put her hand over her mouth. (“She would never volunteer an answer,” Delany recalled, “but whenever I called on her, she always had an answer and it was always very smart.”) But Ellison’s session was a shot in the arm. Butler hadn’t turned in anything all workshop, and his one-story-a-day gauntlet invigorated her. She finished “Childfinder” at 4 a.m. — a story about a Black woman named Barbara who has the ability to locate children with latent psionic abilities and to nurture them. She sold the story to Ellison for his next anthology, The Last Dangerous Visions, and an editor at Doubleday encouraged her to send along her book manuscript for Psychogenesis, a world she had been building out since her teens.

Ellison was a social force: vexing and impossible to feel neutral toward. He would tell Butler to “Write Black!” and “Write the ghetto the way you see it!” — advice that annoyed her. She also had a crush on him. In her journals, she gave him a code name, El Llano, something she did for all of her crushes (William Shatner was “Gelly”). She wanted someone who could help guide her career, and she had hoped Ellison could be her mentor, champion, and lover. “Llano could easily be that master,” she wrote. But she was wary of losing herself. “If I am not careful, he will take over without even realizing it. A master must teach me to use my own talent, not to lean on his. I love him, but this is not what he teaches. So I will continue to love him and teach myself.”

The high of Clarion wore off quickly. Ellison had promised “Childfinder” would make Butler a star, but the publication of The Last Dangerous Visions kept getting delayed. She sent fragments of Psychogenesis to Diane Cleaver, the Doubleday editor she met at the workshop. Cleaver said it was promising but she would need the complete manuscript. Over the next five years, Butler didn’t sell any writing but wrote constantly. She had moved into her own place in Los Angeles, one side of a single-story duplex in Mid City. On Saturdays, she packed a draft of Psychogenesis into her briefcase and went to the library to do research. One day, she lost the briefcase in a department store; from this point on, she always made a backup copy of her work.

She tried to stick to a tight schedule. Every morning at 2 a.m., she woke up to write. This was the best time, before the day was filled with other people, when her mind could roam freely. Sunrise brought the life she did not ask for: menial jobs at factories, offices, and warehouses. She subsisted on work from a blue-collar temp agency she called “the Slave Market.” Her mother wished she would get a full-time job as a secretary, but Butler preferred manual labor because she didn’t have to “smile and pretend I was having a good time.” Her body hurt; she needed to go to the dentist. She took NoDoz to stay awake during the day. She was always crunching numbers: the price of paper, how far she could stretch a $99.07 biweekly paycheck. “Poverty is a constant, convenient, and unfortunately valid excuse for inaction,” she wrote in one journal entry.

The world of Psychogenesis had to do with psionics — telepathy, telekinesis, mind control — which was popular in the science fiction she was reading. The possibility that you could control the circumstances of your life with your mind held a strong appeal for Butler. She believed in its real-world application, too. She had begun taking self-hypnosis classes back in high school and devoured self-help books like The Magic of Thinking Big and 10 Days to a Great New Life. She particularly loved Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich, a book of motivational practices cribbed from the French psychologist Émile Coué’s concept of optimistic auto-suggestion, which originated the mantra “In every day, in every way, I am getting better and better.” She would learn to manifest.

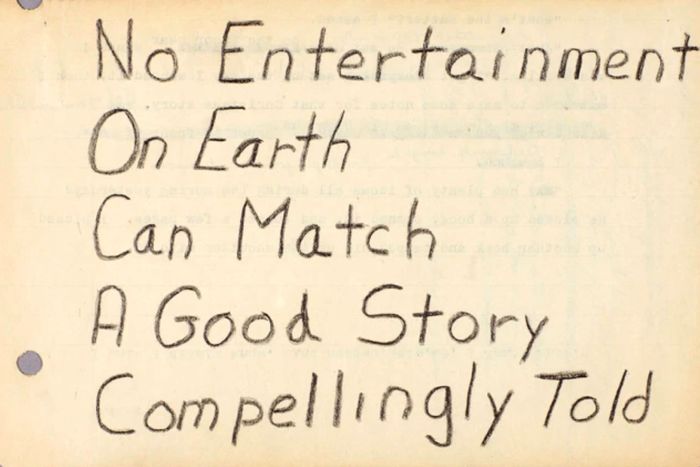

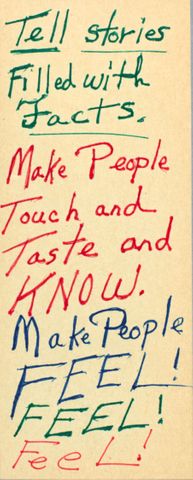

One of Hill’s exercises was to go to a quiet spot and write down a sum of money you want to earn and how you would get it. You had to do it with “faith.” For a stretch of months in 1970, Butler would follow these instructions in the morning and at night. “Goal: To own, free and clear, $100,000 in cash savings,” she wrote. These mantras sounded a drumbeat throughout her early journals. She drew up contracts for herself with writing benchmarks — I will put together an outline; I will complete a short story — and signed them “OEB.” She copied out Frank Herbert’s quote “Fear is the mind killer” and wrote it again, breaking it up into stanzas. Writing was an incantation, a spell she could cast upon herself and the reader. “The goal right now is to achieve a scene of pure emotion,” she wrote. “I want the feeling to spark in the first sentence and I want my reader, my captive to read on helplessly hating with vehemence any interruption strong enough to break through to them. I shall succeed.”

Then, in December 1975, at 28, she sold her first book. After losing the Psychogenesis draft, she began writing another novel, Patternmaster, that takes place in the same universe. It was about a struggle for succession between two psionics, a young upstart named Teray and a seemingly unbeatable being named Coransee, both vying to become the next “Patternmaster” — that is, the leader of the telepathic race known as the Patternists. Butler sent the manuscript to Doubleday. By then, Cleaver had left, and Sharon Jarvis, the science-fiction editor, accepted the submission.

The novels poured out of Butler during this time. While Patternmaster was being finalized, she resurrected Psychogenesis as a prequel (a newfangled concept the jacket copy would describe as a “pre-sequel”) and called it Mind of My Mind. “I have to write about winners — at least until I am one,” she wrote in her journal. In other words, she wrote about characters she aspired to become. In Patternmaster, the two characters are upstaged repeatedly by Amber, a healer neither can control. In Mind of My Mind, a young, Black psionic named Mary discovers she can create a “pattern,” a neural network that brings other psionics under her control. While at first the others bristle, they soon come to discover they enjoy the mental stability her power gives them.

By 1977, Butler had two published novels but was no closer to financial security. Jarvis had given her a $1,750 advance for Patternmaster, which was not enough to live on. Their editor-writer relationship was workmanlike. “What is it you want of Sharon Jarvis?” she asked herself. She had hoped for at least a $2,000 advance for Mind of My Mind as well as “respect, even friendship if such is possible. But definitely respect.” The two wouldn’t meet until after she had published three novels with Jarvis, and Jarvis was surprised to learn Butler was Black. “I went up to her at a science-fiction convention and introduced myself and she opened her mouth, stepped back, and stared,” Butler said. “Then we both played at not knowing why she was behaving that way.” (Jarvis recalled this, too. “When I was an editor, I didn’t give a crap about somebody’s background,” she said.)

Although Mind of My Mind was accepted for publication, Jarvis said there was a catch. At the time, both books were part of Doubleday’s library-subscription project, which earmarked a certain number of genre titles to send to public libraries. Because of this, Jarvis said the books had to be “clean” and expletives would have to be removed for publication. “There is absolutely no problem with any scenes, no necessity for rewriting, but the four-letter words have to come out,” Jarvis wrote in a letter. “Even the use of ‘Christ’ as an expletive must go.” (The N-word, however, was published without concern.)

Butler had been intentional about cuss words, even outlining which ones each character would use. (The character Karl, for instance, would stick to religious outbursts like “Hell!”) She felt the changes made the dialogue stilted and untrue. She wrote back, “I’m not sure I could convince anybody that, for instance, Mary, a feisty (usually) angry lower-class Black woman says ‘Oh shoot!’ or ‘Forget you!’”

“I don’t think the story suffers in any way if you change it,” Jarvis responded. “Consider Barry Malzberg’s words: ‘If it’s money versus integrity, money wins out every time.’” She continued, “If I can take out blatantly offensive words such as fuck and shit and leave the hells and damns, we both can be happy. But I will still have to list Mind of My Mind as a second-stringer with a possible warning attached, so I couldn’t offer more than another $1,750.” (Jarvis said the maximum amount she could offer any author at the time was $3,000.) The exchange became increasingly tense, ending with Jarvis saying she could keep the other expletives, but that fuck was nonnegotiable. “Is that finally clear?” she wrote.

Butler’s relationship with Doubleday continued to deteriorate. She discovered that other science-fiction writers hadn’t heard of Patternmaster and that it wasn’t listed in the catalogue or sold at the Doubleday bookstore in Los Angeles. A review copy of Mind of My Mind hadn’t been sent to Mike Hodel, a radio-show host she was set to do an interview with. In general, there was little to no effort to promote her books beyond the library presales. “I can’t help but feel as though I’m in trouble when I find myself having to bring in proof to booksellers that my book even exists,” Butler wrote. “Take it all in stride,” Jarvis replied when she asked her about these issues. “I’ve heard worse.”

Butler didn’t feel she had other options: She was hoping to sell the company Survivor, the third installment in her series. She didn’t think the book was ready for publication, but she needed the money so she could travel to Maryland to do research for her next book. Jarvis would offer no more than $1,750 for Survivor, either, this time because of a sex scene that she agreed the book “needed.” “What you’ve told me is that a mild three-paragraph sex scene is going to cost me $250,” Butler replied. “I can’t pretend to be happy about that. I accept your offer of $1,750, but I’m not happy.”

Butler would have to promote herself. She sent Patternmaster to Ms. Magazine for review consideration. She regularly attended science-fiction conventions like Westercon to network and sell books. She met a fellow Black science-fiction writer, Steven Barnes, at one of them, and they would commiserate over the years about the lack of support for their work. “How do we win?” said Barnes. “How do we play this game in a way that doesn’t break our hearts and send us to the poorhouse?”

Perhaps because of Butler’s efforts, her books sold better than Doubleday had expected. Jarvis told her Mind of My Mind went into a second printing “because we underestimated the advance sales.” Soon after, Butler received a letter from a young agent at Writers House named Felicia Eth asking if she had representation. Up to that point, Butler’s only experience with an agent had been when her mother paid $61.20 — more than a month’s rent — to a scammer. (“Ignorance is expensive,” Butler would later write.) Writing a best seller was a constant preoccupation — a way to make life financially sustainable. “I need something that sells itself,” she wrote. “Something that screams its significance or its scariness or its timeliness so loudly that it can’t be ignored.”

Her next book would be her first stand-alone novel. Titled Kindred, it represented a new level of maturity for Butler as a writer and has become one of her most enduring works. It blends historical fiction with time travel, sending Dana, a modern-day writer living in Los Angeles, to an antebellum-era plantation in Maryland where she has family roots. The time-travel mechanism is a psychological trap: When the life of one of Dana’s ancestors, a white slave owner named Rufus, is threatened, she is pulled into his orbit to save him. When she believes her own life to be threatened, she returns home. Dana’s existence depends on not only saving Rufus but allowing him to live long enough to rape her other ancestor, a free Black woman named Alice. Butler spent weeks in Baltimore researching at the city’s historical society; she read deeply, including George Rawick’s first 19 volumes of slave narratives, The American Slave; autobiographies by Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs; and journals of slave owners’ wives “to understand that point of view, too.”

Early in her career, Butler received criticism for not writing explicitly about racial politics. “Why do you write that stuff?” she recalled being asked. “You should write something that’s more politically relevant to the struggle.” She first got the idea for Kindred in college when she was a member of the Black Student Union. She had a discussion with another student — male, her age, middle class, and the self-appointed scholar on all things Black history — that she never forgot. “I wish I could kill off all these old people who have been holding us back for so long, but I can’t because I would have to start with my own parents,” she remembered him saying. He believed the older generations were to blame for the lack of racial equity and that they “should have rebelled” against slavery. His impertinence reminded her of herself when she was younger. On days when her mother couldn’t find a sitter, she would bring Butler with her as she worked in other people’s homes. They entered through the back door, and white people spoke in front of them as if they didn’t exist. One day, she told her mother, “I will never do what you do. What you do is terrible.” Normally, her mother would have put her in her place, but that day she didn’t say anything. She just gave her daughter a quiet look.

“I carried that look for a number of years before I understood it,” Butler said in an interview in 2003. “I didn’t have to leave school when I was 10, I never missed a meal, always had a roof over my head because my mother was willing to do demeaning work and accept humiliation. What I wanted to teach in writing Kindred was that the people who did what my mother did were not frightened or timid or cowards, they were heroes.”

Initially, she tried writing Kindred with a male protagonist — not dissimilar from her self-righteous friend — but found she couldn’t keep him alive. A proud Black man like him who would look a white man dead in the eye? He wouldn’t last long enough to learn “the rules of submission.” No, she reasoned, the main character had to be female because her gender would make her seem less threatening. “I was wild for Kindred,” said Eth. “It was a real departure from what people were writing or reading about.” Eth was hoping to sell it as a mainstream title, i.e., not science fiction, and queried numerous publishers: Simon & Schuster, William Morrow, Putnam. Most editors resisted the genre mixing. “The blend of realism and fantasy just didn’t work to my mind,” replied Daphne Abeel at Houghton Mifflin. Gail Winston at Random House liked the book but said she “couldn’t get the support she needed to push it through.” Butler was restless, while Eth counseled patience. Kindred “is a wonderful book because it’s not easily categorized, and we have to expect that that’s going to mean we have to work harder and have more faith in it,” Eth wrote. “I have that faith and don’t want to give up.”

Funnily enough, Kindred ended up at Doubleday: Eth sold it to an editor in the fiction department for $5,000. The book was published in 1979 and received a muted response. While New York legacy media ignored it, it was reviewed in Essence, Ms. Magazine, and science-fiction publications like Locus and Asimov’s Science Fiction. “Black writers did not know I was Black,” she said. “But a couple of experiences helped with that.” One of them came when Veronica Mixon, a young Black assistant editor at Doubleday, pitched the first magazine profile of Butler for a 1979 issue of Essence titled “Futurist Woman.” Kindred fell out of print, but the book allowed Butler to understand where her readership was: in the Black community and among women. Moreover, she began to feel she was owed money commensurate with her work. “I will be sold cheap as long as I permit myself to be sold cheap,” she wrote. “Enough is enough. I will not permit it again.”

In her journals, particularly from the 1970s and ’80s, Butler would deliver self-assessments on her looks, her personality, her comportment. When she was younger and less confident, she often reprimanded herself for saying something she thought was embarrassing. She wanted to become “unembarrassable” but later understood she needed to let go of that. “I maintain distance between myself and other people out of fear. Fear of the pain they will give me if they see me naked. And find me not merely ugly, but foolish and without value,” she wrote. “The defense is not to care.”

In middle age, she would describe herself as “comfortably asocial,” but her journals reflect a deep yearning for intimacy. Loneliness was a constant affliction. She wanted companionship and sex. “Another person would help me to grow up socially,” she wrote. “A lasting relationship would be good for me.” Often, she imagined being with a man: “We want now a man over six feet tall. White, Black, yellow, we do not care.” Still, her relationships with men were not emotionally fulfilling; the sex was brief and “never initiated” by her. During her late 20s, she also imagined herself with a woman. “I know that but for the social stigma, I would rather love women,” she wrote. “I do it so easily. Closeness with men doesn’t seem to fulfill except physically.”

When Butler was 28, she decided to stop living inside her head and meet some women. She worried most about how being in a relationship with a woman could impact her career. “Isn’t being Black and female stigma enough?” she wondered. “It could hurt me. However small I am, it could. If I keep low after coming out, is it fear or shame?” After great hesitation, she picked up the phone to call the Gay and Lesbian Center in L.A. to inquire about some of its upcoming meetups. “Of course it’s possible that the only thing the center group will teach me is that I don’t want to be part of their particular group,” she wrote. “Not that I don’t share their unifying inclination. Why am I being so oblique today? Their lesbianism.”

Her journal from the first meetup burns with an intensity of detail. “A lot of them look like police women — have that odd smugness of ‘authority’ about them, have that ‘tough’ little face, slightly pushed together without being at all ugly,” she observed of the attendees. She noticed that all of them were white. She watched them kiss one another in a way she knew wasn’t “sisterly” and felt pangs of envy. The only time she spoke up was to correct a woman — “white, pretty, and one of those I’d never have suspected” — who was making incorrect claims about parapsychology. (Then she worried about coming off as a killjoy and know-it-all.) She wondered if she was attractive enough and played out scenarios in her head: If she were to pursue this lifestyle, her appearance would mean “the ‘male’ burden would be on me” when courting women.

Butler ended the day in a heap of anguish. If only she had a friend to guide her. She wasn’t confident that women would be interested in her — gay women liked attractive women, just as straight men did. Many of her social anxieties were tied to her lack of money, which she thought having would make her “more civilized, socialized.” At another meeting later in the month, she decided she was done. She sat through the center’s announcements and went home. “I don’t belong there any more than I belong anywhere else,” she wrote. “It would require an effort that I’m not willing to put forth to make me part of those people. They’re not for me. If I found a woman I went well with, we could make it.”

As far as her close friends and editors knew, Butler wasn’t in a romantic partnership. “I am sorry that she did not seem to have that deep, intimate relationship,” said Barnes. “It can be difficult for artists. She had that sense of existential loneliness that human beings get. It was a price she was willing to pay to become the human being that she wanted to be. She became that person, and all it takes to get everything you want is everything you’ve got. Life takes everything.”

Butler never learned to drive. As an adult, she realized she was dyslexic (she hadn’t received an official diagnosis as a child) and needed time to read; she didn’t want to risk trying to read street signs behind the wheel. Instead, she took the bus, an inconvenient way of getting around L.A. and one that created constant proximity with strangers who relied on the same municipal system; it became a steady source of inspiration in her writing. She observed people and occasionally wrote character sketches. During one bus ride, she watched a fight break out: One man accused another of looking at him funny (he wasn’t) and lunged at him. At that moment, Butler thought of the opening line for her next short story, “Speech Sounds”: “There was trouble aboard the Washington Boulevard bus.”

A story set in a dystopic near future in which a pandemic degrades people’s ability to communicate, “Speech Sounds” came out of a depressive period for Butler. It was the early ’80s, and she was languishing with a new novel, Blindsight, which she felt was a “thin and impoverished” version of Mind of My Mind. (It would go unpublished.) Her friend Phyllis was dying of multiple myeloma at the time, and every week, Butler would bring her a new chapter of Clay’s Ark, the fifth Patternist book she was working on, to read. Butler’s Uncle Clarence had recently died, and another friend attempted suicide. Her house had been burgled and the thieves took her typewriters, tape recorders, TV, and radio — something that happened multiple times. She worried about her safety and told Barnes she wanted to take martial-arts classes. “The main thing I felt was wronged,” she wrote after one burglary. “As though I expected the world to be a fair or a sensible place where people see the folly as well as the ‘injustice’ of robbing the poor. I thought, Why did they do it? I had so little.”

Meanwhile, she felt the world was in a state of regression. Butler was a self-professed news junkie with a keen interest in political leaders going back to the Nixon-Kennedy debates. She wanted to understand how their words held sway over people. “Bigotry is easing back into fashion,” she wrote shortly after the presidential election of Ronald Reagan. His attack on social-welfare programs and environmental regulations and the funny math of Reaganomics all filled her with dread. “Reagan is the tool of utterly self-interested, fatally shortsighted men — men who deem it a virtue to be indifferent to human suffering,” she wrote. “We will probably go on solving our problems by borrowing from the future until we are forced by the consequences of our own behavior to change.” She would filter her misgivings into her next series: the Xenogenesis trilogy, which she sold to Warner Books in a three-book deal in 1985. The contract — $75,000, to be divided out around the submission of each installment — was the strongest she had yet received and was buoyed in part by publishers’ renewed interest in science fiction. She sent her mother some money and bought herself a plane ticket to Peru to location-scout for the books.

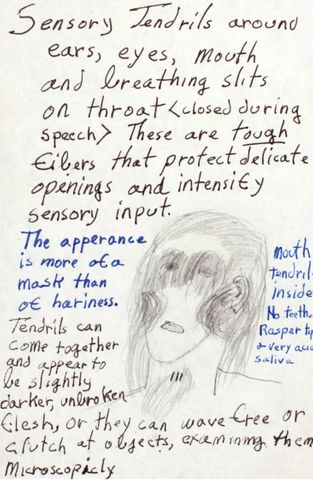

Science fiction can be categorized into three types of stories: “What if?,” “If only,” and “If this goes on.” The first Xenogenesis book, Dawn, was born from Butler’s horror at the Reagan administration’s notion of a “winnable nuclear war” — the worst imaginable scenario of “If this goes on.” Its protagonist, Lilith, is awakened from a cryogenic sleep by an alien race called the Oankali after a nuclear holocaust has destroyed Earth. The Oankali tell Lilith humanity is doomed because of “two incompatible characteristics”: intelligence and a hierarchical nature. Butler designed the Oankali to trigger an instinctive response of fear and disgust; they’re covered in long tentacles like invertebrates. While humans are xenophobic, these aliens are xenophilic. The Oankali give Lilith a “choice” — either go back into a cryogenic-like state or help awaken more humans to mate with the Oankali and start a new race. Essentially, evolve or die. This was the beginning of Butler’s “fix the world” books, her attempts to work out whether humanity could save itself from itself. Throughout the trilogy, she returns to this core observation: that our intelligence and need for dominance would lead to self-annihilation.

Butler’s dire prognosis for the world brought her acclaim. In 1984, she won a Hugo Award for Best Short Story for “Speech Sounds,” followed by another Hugo and her first Nebula for Bloodchild. She returned to Clarion as a teacher the following year. Beacon Press was doing a line of feminist science fiction and bought the rights to reissue Kindred in 1988, a move that would seriously expand the book’s readership. That Christmas, she paid off the mortgage on her mother’s house.

Butler was in her 40s now. She wanted to write her “magnum opus,” but felt she had lost some of the fuel that had kept her going so far. “In a way, I have run dry,” she wrote in a moment of discouragement. “You start to repeat yourself or you write from research and/or formula. I’m like an old prodigy who has run on ‘instinct’ for years, and now must learn her craft all over again because instinct has failed.”

When she was looking for ideas, Butler would do what she called “grazing,” which in practice meant having any number of books open around the house and perusing whatever might be of interest to her: environmental science, anthropology, microbiology, Black history, political studies. Lately, she had been taken by the Gaia hypothesis, an idea tendered by the scientists James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis that Earth is like a human body, a synergistic, self-regulating whole that we are a part of despite our behavior to the contrary.

What if she were to graft this idea onto space-colonization narratives? Wouldn’t a planet reject humans like a body rejecting an organ transplant? What if, instead of enacting the same hostile-native scenario, interstellar colonists were afflicted by the environment and tiny bacteria? Humans would have to learn how to synergize and work with the planet, rather than carry on with their smash-and-grab attitude. This could be a series exploring different worlds and their peculiar challenges. “I’m researching now and playing with ideas, but I know by the way this feels that I’ve got something good,” she wrote in a 1989 letter to her agent, Merrilee Heifetz, who had taken over from Eth. “I’ve a convention and a week of Clarion coming up, so I can’t quite hide out with 30 or 40 books and my typewriter. That’s what I feel like doing. You see, this is what I’m like when I’m in love.”

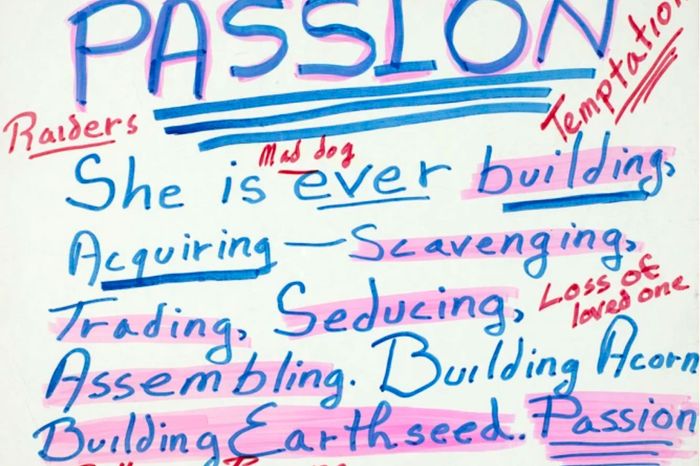

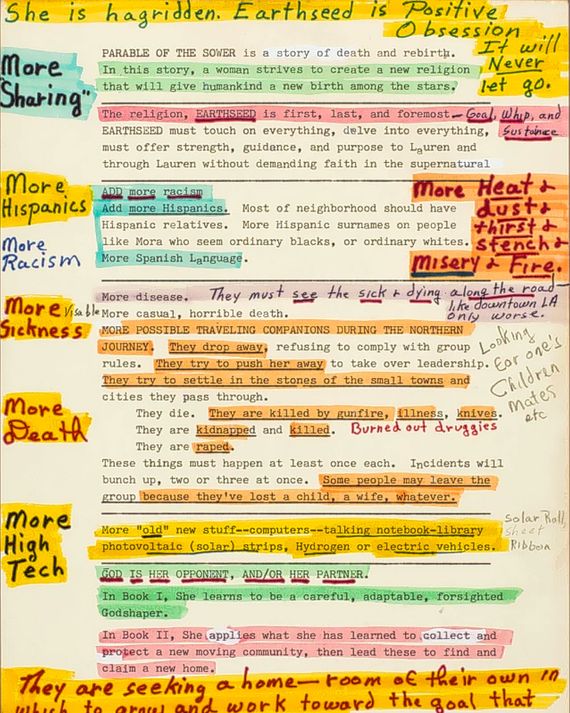

The resulting book, Parable of the Sower, begins in Southern California in the year 2024. Earth, ravaged by the climate crisis called “the Apocalypse,” or “the Pox,” is beyond repair. People have become chained to systems of indentured servitude by company-owned cities. The narrative follows Lauren Olamina, a precocious 15-year-old living in a gated community surrounded by adults who try to fortify its defenses. She knows this safety is an illusion and records her beliefs secretly in a notebook. She suffers from a hyperempathy disorder, a crippling condition that causes her to “feel” what others feel. It forces her to be a tougher, faster decision-maker. She becomes the magnetic leader of a new religion but works slowly and subtly through actions and common sense.

Over four years, Butler rewrote the first 75 pages several times. “Everything I wrote seemed like garbage,” she said. Poetry finally broke the block. “I was forced to pay attention word by word, line by line,” she said. In the book, Lauren calls her belief system Earthseed — a fusion of Heraclitus, Darwin, and the Buddha that revolves around the core principle that “God is change.” She advocates for adaptability and communality as the path of survival for the species. The Earthseed verses take the form of Butler’s own motivational writing, which had transformed from self-help contracts into poetry. “One of the first poems I wrote sounded like a nursery rhyme. It begins: God is power, and goes on to: God is malleable. This concept gave me what I needed,” she wrote. The ultimate goal of Earthseed’s adherents is to shape the Destiny, which will allow humans to “take root among the stars.” Space colonization was Butler’s equivalent to building a cathedral. She believed only some extraordinary feat like space travel could bring people together in a common goal. “Earthseed doesn’t just reconcile science fiction and religion,” wrote her biographer Gerry Canavan. “It remakes science fiction as religion.”

Parable of the Sower was published in 1993. She liked her editor at the time, Dan Simon, who listened when she told him who her various audiences were and sent her out on a book tour. She spoke at independent Black-owned, science-fiction, and feminist bookstores. For the first time, the New York Times reviewed her work (albeit as part of a science-fiction roundup). The greater culture was shifting to meet her. “She was coming into more consciousness because of the growth of Black publishing,” said her writer friend Tananarive Due. “When the Black Books movement took off in the 1990s, a lot of us were caught in that wind.”

On June 9, 1995, Butler received an unexpected call. It was from the MacArthur Foundation, informing her that she had been awarded one of its famed “Genius” grants. She was so surprised that she didn’t ask about the particulars. In her journals, she gave the award a code name: U.B., for Uncle Boisie, a.k.a. A. Guy, possibly as a reference to a male academic who had nominated her. “This isn’t real yet,” she wrote. “It won’t be until the letter arrives. What am I to do? Let us consider sensible behavior.” She would enroll in the foundation’s health plan. She would get life insurance and add her mother as its recipient.

The following week, she got the official letter informing her that she would be granted a total of $295,000 over five years. It would be the largest sum of money she received in her lifetime. The letter read:

Your award carries with it no obligations to the Foundation of any kind. The Foundation has no expectation that your work will retain the form or direction it has to date, nor that you should consult the Foundation about changes. Quite simply, your award is for you to use for whatever purposes you choose.

She made a photocopy of it and, per her habit, started doing the math in the margins: $28,500 in 1995. 1996, $57,500. 1997, $58,500. 1999, $59,500. “A chance to write and to meet daughterly obligations,” she wrote.

A year later, her mother had a stroke and was hospitalized for three weeks before dying. Butler rarely spoke about the death publicly or with friends. “I wrote nothing of value for some time,” she said. Her grief focused her as well. She had been in a rut with Parable of the Talents, the second in the series (which in recent years would become known for featuring a fascist president, Andrew Steele Jarret, who proclaims he will “Make America Great Again”). “Later, when I came back to the novel, I found myself much less inclined to be gentle with my character,” Butler said, referring to Lauren. “Also I found that I needed to see her not only through her own eyes but through those of her daughter.” Butler would say this was “my mother’s last gift to me.” On her mother’s headstone, Butler wrote: “Beloved Mother / Octavia Margaret Butler / 1914–1996 / God is Love.”

A few years after her mother’s death, Butler bought a house in Lake Forest Park just north of Seattle: a three-bedroom ranch-style home with neatly trimmed hedges in front and towering cypress trees in back. She turned one of the bedrooms into a library filled wall to wall with books and another into a study where she would write. Crucially, the house was right off a bus line she could take to U Street to go to events and to the bookstore. She was no longer the girl who would freeze up in class and spoke regularly at conferences, universities, schools, and festivals with authority and presence. In addition to the financial stability, the MacArthur grew her stature. She was the first science-fiction writer to win the grant — a fact the genre’s community seemed to belatedly acknowledge when Parable of the Talents won the Nebula for Best Novel in 2000. That year, Butler also received a PEN Lifetime Achievement Award. “All of the sudden, people who had not paid any attention to my work began to pay attention to me,” she said in an interview with Charlie Rose. Her goal of $100,000 in savings had changed to $1,000,000.

With the completion of the first two Parable books, she had finally set the stage for Earthseed believers to go to the stars. She had an ambitious plan of four more novels with the same title formulation — Trickster, Teacher, Chaos, Clay — set on other planets. True to its name, Parable of the Trickster confounded her. Butler wrote dozens of fragments that never moved beyond exposition. She explored a variety of ailments the planet might afflict on new arrivals: blindness or hallucinations, a body-jumping disease or a “nearly lethal homesickness.” Nothing was working. Republicans continued to depress her, particularly George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan. She needed a break, so she started writing Fledgling, a sexy polyamorous vampire novel, instead.

But writing had become generally difficult. Beginning in the late ’90s, Butler began to feel fatigued. She was taking medication for high blood pressure and heart arrhythmia but felt the drugs were sapping her strength and sex drive. She kept notes of her symptoms — shortness of breath, nausea, back pain, hair loss. Her condition continued to deteriorate into the new millennium. She got pneumonia that was misdiagnosed and left untreated for weeks. Soon, she couldn’t walk more than half a block without getting tired. “I’m not functioning,” she wrote in 2004. “I sit and drowse a lot. I know I’m not thinking very well, and I’m certainly not breathing very well.”

On February 24, 2006, Butler’s friend Leslie Howle was supposed to pick her up to bring her to a local conference. Howle and Butler had met in Seattle in 1985 when Butler was a teacher at Clarion and Howle was a student. Howle remembers her then: young and mosquito bitten and grinning after her trip to Peru. That week, Howle became her chauffeur, a role she would continue to fill over the years, particularly once Butler moved to Seattle. Howle would drive her on grocery runs to Whole Foods and Costco, and they would take hiking expeditions to Wallace Creek, Mount Rainier, and the ice caves. “She really loved getting out in nature,” said Howle. “If Octavia had a place where she saw God, that was it.”

Before she left the house that day to pick up her friend, Howle received word that Butler had died. She had fallen outside of her home, hitting her head on the concrete. She was 58 years old. She had been complaining that weekend about dizziness, nausea, and swollen ankles; she had even called her doctor, who told her she just had the flu and to rest up. Up until then, the medical advice she had received was to exercise more. “I am furious about that because when we’d go hiking, she would be striding up switchbacks and I’d be panting along behind her,” said Howle. “And she’d be like, ‘Oh, do you want me to wait for you?’”

“What happened with Octavia didn’t need to happen,” Howle continued. “Despite being the incredibly powerful person she was, she did not assert herself with her doctor. Even today, doctors discount women of a certain age and women of color. Some of it’s racism, some of it’s ageism, some of it’s sexism — but all the ‘isms’ conspired against her in the end is what I feel. She needed more people who were protective of her.”

Shortly after Butler’s death, Howle organized a memorial service for her at the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame in Seattle. On short notice, over 200 people gathered, including her friends the writers Vonda McIntyre, Nisi Shawl, and Harlan Ellison, via video. Howle remembered the way Butler would end calls by saying, “I’ll be seeing you, then.” Butler’s cousin Ernestine Walker said, “There is an African proverb: ‘As long as you speak my name, I live.’”

Butler’s name has only continued to grow. Since 2004, when BookScan began tracking numbers, over 1.5 million copies of her books have been sold. A Clarion scholarship, her onetime middle school in Pasadena, and a studio lab at the Los Angeles Public Library now all bear her name. In 2021, NASA named the landing site of the Mars Rover Perseverance the Octavia E. Butler Landing Site. The playwright and fellow MacArthur grantee Branden Jacobs-Jenkins had been pitching a television adaptation of Kindred since 2016, but it wasn’t until the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 that networks got serious. His is the first out of the gate. Viola Davis is working on a TV adaptation of Wild Seed for Amazon, Issa Rae and J. J. Abrams are producing Fledgling, A24 acquired the rights to Parable of the Sower, and according to the director of the Butler estate, Jules Jackson, there’s a “humongous bidding war” for Dawn now.

Her most lasting legacy, though, is her writing, published and unpublished. Butler left her papers to the Huntington Library in her will, and she had seemingly kept everything: every journal, notebook, scrap of paper, envelope, contract (official and personal), card, reader letter, photograph, press clipping, diary, datebook, and draft. She kept the correspondence she received and made copies of the letters she sent — just in case. All told, the Octavia E. Butler archive contains 9,062 pieces held in 386 boxes, one volume, two binders, and 18 broadsides. She saved everything except the rejection slips she threw out in a fit of despair when she was young. The archive is evidence of the breadth of a writer’s life: her labor, her joy, her pain, and her greatest love.

Today, her writing is often read inspirationally and aspirationally. Some have taken the tenets of Earthseed literally as a philosophy of living. “Octavia Butler knew” is a common response to cataclysm. Butler did not believe in utopia, but there is a deep strain of hope in how people engage with her work: a desire to learn how to save ourselves from this mess we’ve made. She wasn’t sure imperfect people could ever create a perfect world, but they could try. In an epigram for Parable of the Trickster, she wrote:

There is nothing new

under the sun,

but there are new suns.

What the archives show is how much she struggled with hope herself. She was “a pessimist if I’m not careful.” When she was working on a novel, her drafts tended to reveal the crueler sides of human nature. She didn’t like Lauren Olamina at first because she saw the character as a power seeker. Earlier iterations of Parable depicted her as a calculated leader who orders assassinations on her enemies and puts shock collars on those who try to leave Earthseed. But the version of Lauren in the finished book is wise, practical, strong — someone who could grow a community into a movement. If Butler had been writing idealized selves since childhood, Lauren was the young adult she wished she had been, and her rise into myth has come to resemble her character’s. You could understand this as a function of her desire for commercial success: We all need heroes. But another way to see it is that hope is not a given. It was through rewriting that she was able to imagine not only the darkest possible futures, but how to survive within them. Hope and writing were an entwined practice, the work of endless revision.

An earlier version of this piece incorrectly stated the Kindred series will be coming to FX. It will air on Hulu.

No comments:

Post a Comment