https://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/nov/12

~~ recommended by collectivist action ~~

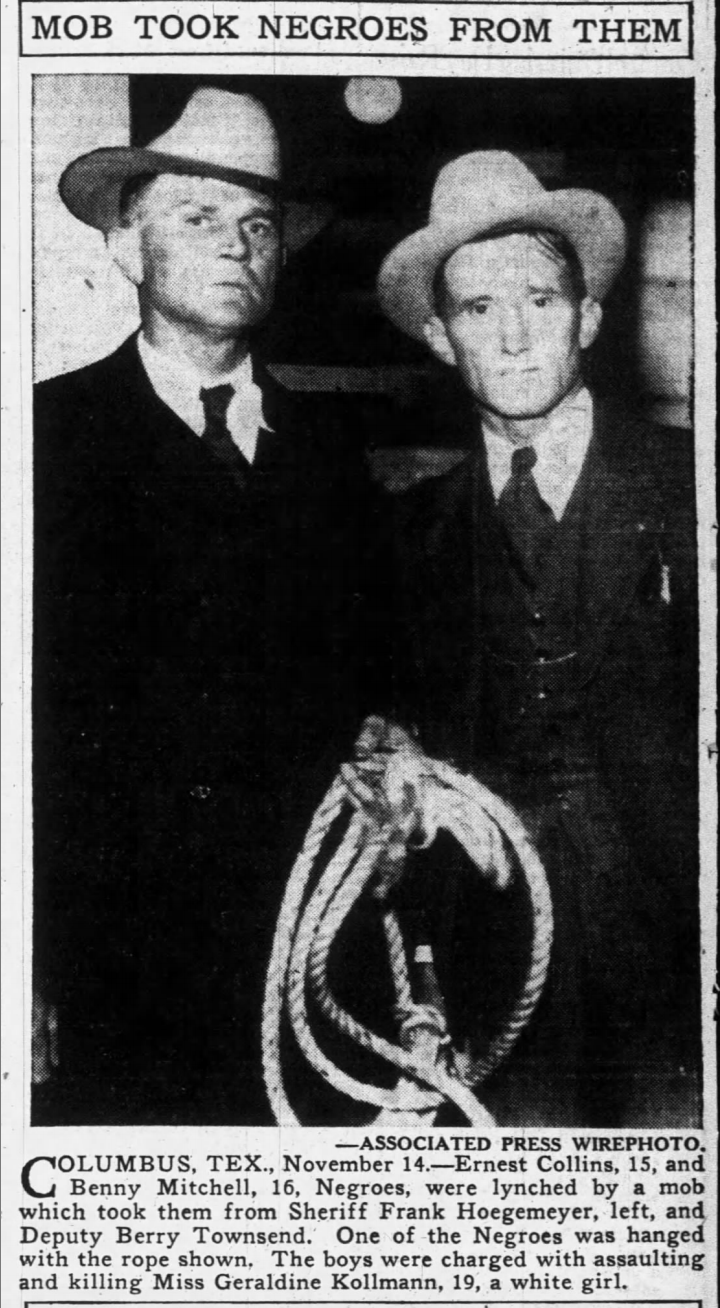

On November 12, 1935, a mob of at least 700 white men, women, and children killed two teenaged Black boys—15-year-old Ernest Collins and 16-year-old Benny Mitchell—in Colorado County, Texas, in a public spectacle lynching. Afterward, officials called the lynching “justice,” and no one in the mob was punished.

In October 1935, a young white woman’s body was found in a creek near her family’s farm in Columbus, Texas. When local officials concluded she had been murdered, suspicion soon focused on Ernest Collins and Benny Mitchell: two Black teens who had been seen picking pecans near the same creek. During this era, the deep racial hostility that permeated Southern society burdened Black people with a presumption of guilt that often served to focus suspicion on Black communities after a crime was discovered, whether evidence supported that suspicion or not.

Law enforcement officers arrested Ernest and Benny and, soon after, reported that the young men had confessed to the crime. Black suspects in the South during this time were regularly subjected to beatings, torture, and threats of lynching during police interrogations. News reports eagerly reported Ernest’s and Benny’s alleged confessions as truthful justifications for the brutal lynchings that followed, but without fair investigation or trial, their supposed confessions serve as more reliable evidence of fear than guilt.

The boys were held in Houston after arrest until they had to return to Columbus for a trial on November 12. While the sheriff was transporting Benny and Ernest to the Colorado County courthouse, several cars filled with armed white men stopped them on a bridge crossing and demanded to lynch the two boys. The sheriff handed them over.

Immediately, the white mob brought Ernest and Benny to a live oak tree about a mile from the young white girl’s home and prepared to kill them. A crowd of at least 700 people gathered to watch and repeatedly “burst into jeering screams” as Ernest and Benny, who had been chained together by their necks, were led to the tree. Several members of the mob placed ropes around the boys’ necks and hanged them until dead.

The next day, the white community proudly boasted and praised the lynchings. The county attorney publicly said the lynching was “an expression of the will of the people” and a local judge called the lynchings “justice.” Several newspapers reporting on the lynchings printed an image of two local sheriff officials posing with one of the lynching ropes, and both ropes were exhibited in a local drug store. Local press was silent about the lynching's impact on the local Black community. Though the mob members and spectators were widely known, no one was immediately arrested or charged for their actions.

Since the end of Reconstruction in 1877, racial terror lynchings targeting Black communities had killed thousands of men, women, and children throughout the U.S., but repeated calls for a federal anti-lynching law had failed due to obstruction by Southern white lawmakers. In 1935, the same year that Benny Mitchell and Ernest Collins were lynched, the Costigan-Wagner anti-lynching bill was introduced in the U.S. Senate. Texas’s own Sen. Tom Connally opposed the bill, and claimed that states were capable of stopping lynching without “federal interference.” Within weeks of the lynchings of Benny and Ernest, the NAACP protested the lack of any state or local investigation and insisted it clearly showed that many states could not—or would not—act to stop the lynching of Black people. The bill ultimately failed, and the U.S. Congress never passed anti-lynching legislation during the 20th century.

Ernest Collins and Benny Mitchell are two of at least seven African American victims of racial terror lynching killed in Colorado County, Texas, between 1877 and 1950. No one was ever held accountable for their deaths. To learn more, read EJI's report, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.

The Galveston Daily News

On November 13, 1957, Longview, Texas, Police Chief Roy Stone threatened four top-ranking NAACP officers—Reverend S.Y. Nixon, I.S. White, E.C. Hawkins, and Rance James—phoning each of the men at home and stating he would jail them if they did not produce NAACP membership records immediately. Chief Stone acted under the authority of a new Longview city ordinance that gave the City Manager the power to demand membership lists from any organization operating within the city’s limits, and to impose criminal fines for non-compliance. Within 24 hours, Chief Stone made good on his threat, arresting Mr. Nixon, Mr. White, Mr. Hawkins, and Mr. James, and detaining them in the city jail. Longview City Judge Henry Atkinson set bail at $200.

On October 9, the Texas NAACP announced plans to host the organization’s annual state conference in Longview. During planning meetings, local white officials refused to allow the Texas NAACP to convene in Longview unless they produced membership lists. During one meeting on October 23, white Longview journalist Carl Estes physically assaulted Field Secretary Washington and forced Black organizers out of his office after the NAACP declined to disclose confidential information about its members.

The following day, the Longview City Commission passed the mandatory disclosure ordinance targeting the Texas NAACP. Every city commissioner endorsed enforcement of the ordinance, knowing that requiring the NAACP to disclose its membership lists could have disastrous and deadly consequences for its members. On October 27, NAACP Field Secretary Washington announced plans to move the Texas annual conference to Dallas, considering “the pressures, threats, ugliness, and distress” that Black civil rights leaders faced in Longview.

Membership in the NAACP or participation in civil rights work often meant that Black people would be fired from their jobs, harassed by the police and become targets of vigilante violence and hate crimes. African Americans joined despite the threats because of their commitment to end racial inequality, but the risks were real.

The passage of this ordinance in Longview led to the passage of a new state law, enacted in December 1957, modeled on the Longview ordinance, which authorized county judges to demand confidential records from civil rights organizations. In 1958, in NAACP v. Alabama ex rel Patterson, the U.S. Supreme Court declared these mandatory disclosure laws unconstitutional, as violative of the First Amendment right to freedom of association.

Associated Press

On November 14, 1960, four federal marshals escorted six-year-old Ruby Bridges to her first day of first grade as the first Black student to attend previously all-white William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, Louisiana. A riotous white mob organized by the local White Citizens' Council gathered to protest her arrival, screaming hateful slurs, threats, and insults.

In August 1955, African American parents in New Orleans, Louisiana, sued the Orleans Parish School Board for failing to desegregate local schools in compliance with the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education. The following February, a federal court ordered the school board to desegregate the city’s schools. For the next four years, the school board and state lawmakers defied the federal court's order and resisted school desegregation.

On May 16, 1960, Judge J. Skelly Wright issued a federal order demanding the gradual desegregation of New Orleans public schools, beginning with the first grade—but the Orleans Parish School Board convinced Judge Wright to accept an even more limited desegregation plan, requiring African American students to apply for transfer into all-white schools. Only five of the 137 African American first graders who applied for a transfer were accepted; four agreed to attend, including six-year-old Ruby Bridges, who was the sole Black student assigned to William Frantz Elementary.

After getting past the angry white crowd to enter the school, Ruby arrived in her assigned classroom to find that she and the teacher were the only two people present; it would remain that way for the rest of the school year. Within a week, nearly all of the white students assigned to the newly-integrated elementary schools in New Orleans had withdrawn.

Despite threats and retaliation against her family, including her grandparents’ eviction from the Mississippi farm where they worked as sharecroppers, Ruby remained at Frantz Elementary. The next year, Ruby advanced to the second grade, and the school's incoming first grade class had eight Black students.

Library of Congress

On November 15, 1830, North Carolina passed two laws designed to limit the influence of an anti-slavery pamphlet and discourage its dissemination, mandating the punishment of death for those who twice violated the law. About a year earlier, in September 1829, David Walker, a free Black abolitionist and activist living in Boston, Massachusetts, published An Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World. The anti-slavery pamphlet advocated for racial equality and called for free and enslaved Black people to actively challenge injustice, racial oppression, and the institution of slavery.

The Appeal was the first published document to demand the immediate and uncompensated emancipation of enslaved people in America. Mr. Walker also indirectly targeted his pamphlet to white readers, urging them to cease their inhumane treatment of enslaved people.

The pamphlet was quickly and clandestinely circulated among Black people, especially in the South, inciting anger among many white people and sometimes swift and harsh punishment. Jacob Cowan, a literate enslaved man in North Carolina, was sold “downriver” to Alabama after he was caught with 200 copies of the pamphlet for distribution to other enslaved people in the community. Copies of the pamphlet found by Southern officials were destroyed, the State of Georgia offered a bounty for Mr. Walker’s capture, and several Southern states—like North Carolina—eventually passed laws to further oppress both enslaved and free Black people.

Titled "An Act to Prevent the Circulation of Seditious Publications," North Carolina's first law banned bringing into the state any publication with the tendency to inspire revolution or resistance among enslaved or free Black people; a first violation of the law was punishable by whipping and one-year imprisonment, while those convicted of a second offense would “suffer death without benefit of clergy.”

The second law forbade all persons in the state from teaching the enslaved to read and write. A white person convicted of violating the law would be subject to a $100-200 fine or imprisonment; a free Black person would face a fine, imprisonment, or between 20 and 39 lashes; and an enslaved Black person convicted of teaching other enslaved people to read or write would receive 39 lashes.

On November 16, 1900, a 15-year-old Black teenager named Preston “John” Porter Jr. was burned alive while chained to a railroad stake in Limon, Colorado. A mob of more than 300 white people from throughout Lincoln County gathered to participate in the brutal public spectacle lynching.

Earlier in the year, Preston, his father, Preston Porter Sr., and his brother, Arthur Porter, moved to the Limon, Colorado, area from Lawrence, Kansas, to seek work on the railroad. When a white girl named Louise Frost was found dead in Limon on November 8, a search began for possible suspects. Newspapers reported that the Porter family had left Limon for Denver a few days after the girl was found dead, and white authorities focused suspicions on them. On November 12, all three were arrested and taken to the city jail in Denver.

During this era, the deep racial hostility that permeated American society burdened Black people and communities with presumptions of guilt and dangerousness when crimes were discovered. Allegations against Black people were rarely subject to serious scrutiny, and mere accusations of assault or violence by a Black person towards a white person often incited mob violence and the threat of lynching.

After the Porters had been in jail for four days, newspapers reported that Preston had confessed to the crime “in order to save his father and brother from sharing the fate that he believes awaits him.” Black suspects were often subjected to beatings, torture, and threats of lynching during police interrogations. While news reports often reported these confessions as justifications for the brutal terror lynchings that followed, the confession of a lynching victim was always more reliable evidence of fear than guilt.

Despite the Governor's order to not transfer Preston back to Lincoln County for at least eight days following Preston's confession, the sheriff of Lincoln County prematurely transported Preston by train from the Denver jail to return to Lincoln County. When the train stopped just outside of Limon, a mob of 300 or more people—including Louise Frost’s father—were waiting. Newspapers described the lynching as follows:

[Preston] was said to have been reading a Bible and was allowed to pray before his lynching. When the flames reached his body, reports documented his screams for help as he writhed in pain, crying, “Oh my God, let me go men!...Please let me go. Oh, my God, my God!” When the ropes binding [Preston] to the stake had burned through, such that his body had fallen partially out of the fire, members of the mob threw additional kerosene oil over him and added wood to the fire. It was reported that [Preston's] last words were “Oh, God, have mercy on these men, on the little girl and her father!”

Despite ample press coverage identifying multiple members of the mob, no investigation into the lynching was conducted and the coroner concluded Preston died “at the hands of parties unknown.” Following the lynching, Preston's father and brother left Colorado to return to Kansas and soon afterward the Colorado legislature voted to reinstate the state’s death penalty to avoid future “lawlessness” like the lynching in Limon.

Preston “John” Porter Jr. is one of more than 6,500 documented African American victims of racial terror lynching killed in the U.S. between 1865 and 1950, and one of five killed in Colorado.

Atlanta Black Star

On November 17, 1937, over 1,000 white students and faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill gathered to attend a speech openly advocating for white supremacy by the Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, Dr. Hiram Evans. The UNC Political Science Department and the Carolina Political Union hosted the event, entitled “America and the Klan.” Amidst the rise of Nazism in Europe, Dr. Evans told students, “What America needs most now to restore the good old days when nations loved each other is a universal dose of the Ku Klux Klan.”

Dr. Evans said that “the Klan will continue to insist on white supremacy, for experience has shown that nations that have mixed breeds with the Black race have found themselves headed for destruction.” Dr. Evans also urged that “America had admitted too many foreigners” who were “responsible for most of our country’s social and economic ills,” and that “America must be dominated by Americans, not by Negroes or aliens.” He warned students of the rise of Black leadership in the South, urging white students and faculty to join the Klan to combat Black political power.

As Dr. Evans spewed racism and intolerance, the more than 1,000 white students and faculty showed support and enjoyment of racial insults and threats throughout the event.

Locals viewed Dr. Evans’ visit as an attempt to launch a new public KKK chapter. In covering Dr. Evans’ 1937 speech, the Daily Tar Heel, Carolina’s student newspaper, noted that since the chapter first launched privately in 1921, “The KKK has grown to the strongest secret organization in existence.”

Carolina’s ties to the Klan persisted well into the 21st century. In the 1920s, UNC named Saunders Hall, a campus building, after William Saunders, the leader of the North Carolina Ku Klux Klan.

Despite decades of student activism seeking to change this name, Saunders Hall remained the name on the building until 2015.

On November 18, 1983, a Black man named James Cody was beaten with a flashlight, subjected to electric shock on his testicles and buttocks, and threatened with castration by officers acting under Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge. Over the course of almost 30 years, Commander Burge oversaw and participated in the torture of over 100 Black men, resulting in scores of forced confessions. When Commander Burge first took command of the jurisdiction known as Area 2 as a detective in 1972, he and his men—known as the “Midnight Crew”—began forcing confessions using brutal torture practices such as beating, suffocation, electric shock, burning, Russian roulette, and mock execution.

In 1982, Cook County State’s Attorney Richard Daley was notified of Commander Burge's tactics through a letter detailing Commander Burge's abuse of a man named Andrew Wilson, who was beaten, shocked, suffocated, burned with a radiator, and threatened with a gun in his mouth. Mr. Wilson sued the city in one of numerous complaints and lawsuits alleging torture by Commander Burge and his men. Despite these complaints, the State’s Attorney’s office continued to use confessions obtained by Commander Burge's team to convict and incarcerate dozens of Black men over the next 10 years.

An investigation into the torture allegations was not launched until 1991, following pressure from advocacy groups, international human rights organizations, and torture survivors. Two years later, Commander Burge was fired, and 15 years after that, he was convicted of perjury for lying under oath in one of the civil suits; he served less than four years in prison. In 2015, the city of Chicago approved a $5.5 million reparations package for survivors of the Burge-led torture campaign. The settlement included a formal apology as well as curricular reforms that would highlight the survivors’ stories in schools. Despite the review and reversal of many convictions that were obtained under Commander Burge’s command, in 2015 more than a dozen survivors remained in prison and had not yet had their cases reviewed.

Library of Congress

On November 19, 1906, dozens of Black veterans who were wrongfully discharged from the 25th Infantry Regiment, a segregated unit stationed at Fort Brown, Texas, went to San Antonio seeking work. In a coordinated effort, white employers throughout the city uniformly refused to hire these men in an attempt to drive them out of town.

Over the summer of 1906, Black soldiers of the segregated 25th Infantry Regiment were stationed by the U.S. Government in Fort Brown, Texas, even though the War Department recognized that Black soldiers would “not be welcomed” there and would be at risk for racial violence. While stationed at Fort Brown, Black soldiers were subjected to segregated facilities and barred from most establishments and parks in nearby Brownsville.

On the evening of August 13, 1906, shots were fired into civilian homes in Brownsville by an unknown group of individuals. When police arrived at the scene, an altercation ensued, leaving a white man, who was hit by stray bullets, dead and a police officer wounded. Without any evidence identifying those responsible, suspicion quickly turned to a group of Black soldiers of the 25th Regiment.

When questioned by authorities, Fort Brown’s all-white military commanders corroborated the alibis of these Black soldiers, affirming that the soldiers remained in their barracks at the time of the shooting. Despite this strong evidence of their innocence, Brownsville authorities charged 12 Black soldiers with murder. The soldiers repeatedly and consistently stated they had no knowledge of the attack or those who were involved.

Attempting to force confessions from this group of innocent Black soldiers, the federal government gave the entire regiment a deadline to come forward with information about the August 13 incident or face the consequences. When no soldiers came forward, in an action unprecedented in U.S. history, President Theodore Roosevelt issued an executive order dishonorably discharging not only the 12 accused men, but the entire unit—167 Black soldiers of the B, C, and D companies of the 25th Infantry—from the U.S. Army on November 6 for their “conspiracy of silence.” The order further barred the men from ever re-enlisting in the U.S. military or applying for a civil service position with the federal government.

In the wake of being discharged, these innocent Black veterans, who had bravely chosen to serve the U.S., were forced to navigate the presumption of guilt and dangerousness, despite never having a trial or being convicted of any crime, and were subjected to mistreatment and abuse, as exemplified by the white employers in San Antonio who colluded to deny them employment. Some of these veterans had served in the military for over 20 years, but because of this action, were denied their pensions.

In 1972, the U.S. government re-investigated the incident and exonerated all soldiers in the 25th Infantry. To learn more about the targeting of Black soldiers and veterans, read EJI’s report, Lynching in America: Targeting Black Veterans.

Montgomery Advertiser

On November 20, 1955, a white church board in Durant, Mississippi, voted unanimously to fire a Presbyterian minister, Rev. Marsh Callaway, after he defended racial integration and spoke out against the White Citizens’ Council in Holmes County.

In September, a group of white people in nearby Tchula, Mississippi, demanded that Dr. David Minter and Eugene Cox, two white men who operated a cooperative farm, leave the community for supporting racial integration. Dr. Minter served as a physician and, alongside Mr. Cox, had assisted the Black community in Holmes County with medical care and aid over the prior 17 years. When news spread that the two men supported racial integration and allegedly permitted Black and white teenagers to swim in a pond together near the farm, an officer of the White Citizens’ Council called a meeting to vote to remove these two men from the community.

Like White Citizens’ Councils across the country, the White Citizens’ Council in Holmes County was committed to preserving racial segregation and white supremacy in all aspects of life. In 1955, 250 White Citizens’ Councils had formed throughout the South, composed of a total of 60,000 members, and by 1957, membership reached 250,000.

During the meeting attended by at least 400 white people from Holmes County, as individuals gathered to vote on the removal of Dr. Minter and Mr. Cox from the community, Rev. Callaway, a minister at the Durant Presbyterian Church, stood up in opposition, calling the meeting “undemocratic and un-Christian.” He praised Mr. Cox as “a fine Christian man,” to which the crowd booed and hissed him into silence. Shortly after the meeting, Rev. Callaway was asked by his white congregation to resign as minister because his support for integration caused “many of the church members to lose faith in the minister.”

In the week prior to Rev. Callaway’s public condemnation of the White Citizens’ Council, Durant Presbyterian had one of the “largest crowds in several months” attend church services. The following week, church members of the Durant Presbyterian Church boycotted services because Rev. Callaway had spoken out at the meeting. On November 20, members of the church voted unanimously for Rev. Callaway's immediate removal, citing “personal conflict.” He was fired after approval by the Central Mississippi Presbytery.

To learn more about millions of Americans’ commitment to racial segregation, read the Equal Justice Initiative’s report, Segregation in America.

Carolyn Hong Chan

On November 21, 1927, in Gong Lum v. Rice, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the Chinese-American Lum family and upheld Mississippi’s power to force nine-year-old Martha Lum to attend a "colored school" outside the district in which she lived. Applying the “separate but equal” doctrine established in 1896's Plessy v. Ferguson decision, the Court held that the maintenance of separate schools based on race was “within the constitutional power of the state legislature to settle, without intervention of the federal courts.”

First adopted in 1890 following the end of Reconstruction, the Mississippi Constitution divided children into racial categories of Caucasian or “brown, yellow, and Black,” and mandated racially-segregated public education. In 1924, the state law was applied to bar Martha Lum from attending Rosedale Consolidated High School in Bolivar County, Mississippi—a school for white students. Martha’s father, Gong Lum, sued the state in a lawsuit that did not challenge the constitutionality of segregated education but instead challenged his daughter’s classification as “colored.”

When the Mississippi Supreme Court held that Martha Lum could not insist on being educated with white students because she was of the “Mongolian or yellow race,” her father appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. In its decision siding with the state of Mississippi, the Court reasoned that Mississippi’s decision to bar Martha from attending the local white high school did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment because she was entitled to attend a colored school. This decision extended the reach of segregation laws and policies in Mississippi and throughout the nation by classifying all non-white individuals as “colored."

Library of Congress

On November 22, 1865, the Mississippi legislature passed “An Act to regulate the relation of master and apprentice, as relates to freedmen, free negroes, and mulattoes.” Under the law, sheriffs, justices of the peace, and other county civil officers were authorized and required to identify all minor Black children in their jurisdictions who were orphans or whose parents could not properly care for them. Once identified, the local probate court was required to “apprentice” Black children to white “masters or mistresses” until age 18 for girls and age 21 for boys.

After the physical and economic devastation of the Civil War, Southern states faced the daunting task of rebuilding their infrastructures and economies. At the same time, the young white male population had been drastically reduced by war-time casualties and emancipation had freed the formerly enslaved Black labor that had largely built the entire region. In response, some Southern state legislatures passed race-specific laws to establish new forms of labor relations between Black workers and white “employers” that complied with the letter of the law on paper, but actually sought to recreate the enslaver-enslaved conditions of involuntary servitude that existed prior to emancipation.

Though the law did not require white "employers" to pay the children they "hired" a wage, the law did require them to pay the county a fee for the apprentice arrangement. The law claimed to require white “masters” to provide their apprentices with education, medical care, food, and clothing, but it also re-instituted many of the more notorious features of slavery. The children's former enslavers were given first opportunity to hire those formerly enslaved by them, for example. In addition, the law authorized white "masters" to “re-capture” any apprentice who left their employment without consent, and threatened children with criminal punishment for refusing to return to work.

Ty Wright for The New York Times

On November 23, 2014, Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old Black boy, died from injuries inflicted when he was shot by a white police officer the day before. Tamir was playing in a park near his Cleveland, Ohio, home when a police car approached him; within seconds, before Tamir could be questioned or warned, Officer Timothy Loehmann shot Tamir in the stomach.

The officers were responding to a 911 dispatch in which a caller had reported that someone in the park was playing with a gun. The caller also explained to the dispatcher that the person was “probably a juvenile” and the gun was “probably fake.” Tamir was, in fact, playing with a toy gun in the park—as countless children have—and was immediately shot to death by police despite posing no threat to anyone.

Immediately after the shooting, police tackled Tamir’s 14-year-old sister as she rushed to his side, handcuffed her and held her in the back of their squad car unable to comfort her injured brother. Tamir’s mother was also prevented from going to her son, and threatened with arrest if she did not “calm down.” Neither Mr. Loehmann nor his partner, Frank Garmback, attempted to administer critical lifesaving procedures to Tamir as he lay bleeding immediately after the shooting.

After the December autopsy was released, Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner Thomas Gilson reaffirmed his initial ruling that the shooting was a homicide and in June 2015, the Cleveland Municipal Court found probable cause for prosecutors to proceed with charges of murder and other offenses against Officer Loehmann. County Prosecutor Timothy McGinty instead declared that he would wait to follow a grand jury’s recommendation. A grand jury ultimately refused to indict Mr. Loehmann on any charges.

On November, 24, 1958, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously decided Shuttlesworth vs. Birmingham Board of Education, rejecting a challenge to Alabama’s School Placement Law. The law, designed to defy the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision and maintain school segregation, allowed Alabama school boards to assign individual students to particular schools at their own discretion with little transparency or oversight.

Alabama’s School Placement Law, which claimed to allow school boards to designate placement of students based on ability, availability of transportation, and academic background, was modeled after the Pupil Placement Act in North Carolina—enacted on March 30, 1955, in response to the Brown decision. Virginia passed the second placement law on September 29, 1956. In 1957, after the North Carolina law was upheld by a higher court, legislatures in other Southern states passed similar pupil placement laws; by 1960, such laws were on the books in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and the city of Atlanta, Georgia.

After the Alabama law's passage, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth sued on behalf of four African American students in Birmingham who had been denied admission to white schools that were closer to their homes. In its unanimous decision, the Supreme Court wrote, “The School Placement Law furnishes the legal machinery for an orderly administration of the public schools in a constitutional manner by the admission of qualified pupils upon a basis of individual merit without regard to their race or color. We must presume that it will be so administered.”

Between the Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954 and 1958, a total of 376,000 African American children were enrolled in integrated schools in the South. This growth slowed significantly as states passed obstructive legislation like these pupil placement laws; the figure rose by just 500 students between 1958 and 1959, and by October 1960, only 6% of African American children in the South were attending integrated schools. Crucially, in the five Deep South states, including Alabama, every single one of 1.4 million Black schoolchildren attended segregated schools until the fall of 1960. Learn more about the massive white resistance to integration in this period here.

Hillsborough (NC) Recorder

For decades, the University of North Carolina had an active slave leasing program, whereby the University “leased” hundreds of enslaved Black people to students for a fee. On November 25, 1829, after a Black man escaped the University grounds and sought his freedom, rewards were issued to effectuate his recapture and re-enslavement on UNC grounds.

Through this slave leasing program, UNC engaged in the active trafficking of enslaved Black people, by collecting fees from students to “lease” enslaved Black people back to them. Students paid a yearly fee in their tuition directly to the University for the labor of enslaved Black people. The University maintained contract agreements with plantations and local enslavers in Orange and Chatham County, as well as the University’s employees, trustees, and presidents, who “leased” Black people they enslaved to the University. Consequently, through this trafficking program, UNC not only increased its revenue, but also enriched local enslavers.

Until 1845, students from families who enslaved Black people were permitted to bring enslaved people with them to campus. After 1845, the University prohibited students from bringing enslaved people to campus, but still authorized students to pay the University to “lease” enslaved Black people on campus. In 1860, 464 Black people were enslaved for the benefit of students, faculty, and employees at UNC.

On November 25, 1829, as part of this trafficking scheme, a graduate of UNC issued rewards for the capture of a Black man named James who had been trafficked to work at the University for the prior four years. James had sought his freedom from enslavement and ran away from campus. The ad was placed in several local newspapers, and encouraged people with information about James’s whereabouts to direct their correspondence to UNC to effectuate his recapture.

In addition to the leasing program which trafficked enslaved Black people onto the grounds of the University, UNC participated in and profited from the sale of Black people. In its founding charter in 1789, the University was given the right to sell enslaved Black people who had been enslaved by local white people who died without heirs. Under this agreement, white enslavers’ “property,” including enslaved Black people, was escheated to the University’s Board of Trustees. In the 1840s, 10 years after the reward for James was announced, following the death of a local enslaver, the University sold the Black people that person had enslaved, earning $2,800, which amounts to approximately $83,000 dollars today.

To learn more about the history of enslavement in America, read the Equal Justice Initiative’s report, Slavery in America.

On November 26, 1957, during a special Legislative session called to pass segregation laws, the Texas legislature voted overwhelmingly (115-26) to pass a bill giving Governor Price Daniel the power to immediately close any school where federal troops might be sent to enforce integration.

The Texas legislature passed the bill just a few months after President Dwight Eisenhower deployed federal troops to Arkansas and commanded the Arkansas National Guard to escort nine Black students, known as the Little Rock Nine, to their first day of school at Central High School amid violent threats from white community members. In passing this bill, the state legislators made clear that they would rather everyone at a school be denied education than allow Black students to attend previously all-white schools.

During the same session another bill was passed that provided school districts with legal aid should integration suits be brought up against them.

Bills like these, and the broader massive resistance to integration by white officials and community members, were largely successful in preventing integration of schools in the South. In the five Deep South states, every single one of 1.4 million Black school children attended segregated schools until the fall of 1960. By the start of the 1964-65 school year, less than 3% of the South’s Black children attended school with white students, and in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina that number remained substantially below 1%. In 1967, 13 years after Brown v. Bd. of Education, a report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights observed that white violence and intimidation against Black people “continues to be a deterrent to school desegregation.”

On November 27, 1995, the Weekly Standard published an article by Princeton University political science professor John Dilulio. Entitled “The Coming of the Super-Predators,” the article predicted the U.S. would be home to 270,000 violent youth by 2010. According to Dilulio, growing rates of “moral poverty” were causing aggressive behavior among poor and minority youth and were building toward a crisis.

Dilulio's “super-predator” language came to be commonly used in conjunction with dire predictions that a vast increase in violent juvenile crime was looming. Theorists suggested that the nation would soon see “elementary school youngsters who pack guns instead of lunches” and who “have absolutely no respect for human life.” Much of the frightening imagery was racially coded. For example, in “My Black Crime Problem, and Ours,” Dilulio warned of “270,000 more young predators on the streets than in 1990, coming at us in waves over the next two decades ... as many as half of these juvenile super-predators could be young Black males.”

Panic over the impending crime wave expected from these “radically impulsive, brutally remorseless” children led nearly every state to enact legislation mandating automatic adult prosecution for children, permitting sentences of life without parole or death for children, and/or allowing children to be housed with adult prisoners. But the predictions proved wildly inaccurate. Lower rates of juvenile crime from 1994 to 2000 despite simultaneous increases in the juvenile population led academics who had originally supported the “super-predator” theory to back away from their predictions, including Dilulio himself. In 2001, the U.S. Surgeon General labeled the “super-predator” theory a myth.

Efforts to reverse the policies that grew from the “super-predator” myth have seen some success in the Supreme Court, which in 2005 decided in Roper v. Simmons that the death penalty is unconstitutional for juveniles. In 2010, the Court in Graham v. Florida prohibited life imprisonment without parole sentences for children convicted of non-homicide crimes. And in 2012, the Court's decision in Miller v. Alabama invalidated mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles convicted of homicide. Meaningful implementation of these decisions, as well as further reform, remains an ongoing effort and challenge. But tens of thousands of children prosecuted as adults as a result of this misguided, racially biased rhetoric still remain in American jails and prisons today.

Learn more about the impact of the "super-predator" myth here and read Dilulio's original article here.

The Kansas City Star

On November 28, 1933, a mob of 7,000 white men, women, and children seized an 18-year-old Black man named Lloyd Warner from the jail in St. Joseph, Missouri, hanged him, and burned his body in a brutal public spectacle lynching.

Just hours before, news spread that a Black man had allegedly assaulted a white girl. Mr. Warner was quickly accused of being the perpetrator, arrested, and placed in jail. As was typical of the era, the mere accusation that a Black man had sexually assaulted a white girl aroused a violent white mob that gathered outside the jail armed with ice picks, firearms, and knives. Mr. Warner professed his innocence to a court-appointed lawyer who remained at the jail with him, but the threat of lynching grew.

Outside, the crowd swelled to 1,000 people, and the state governor deployed National Guardsmen, allegedly to quell the mob. For at least three hours, in a standoff with local law enforcement and national troops, mob members demanded the sheriff turn over Mr. Warner. Neither the National Guardsmen nor local law enforcement took actions to defend the jail or dispel the mob, even as mob members smashed jail windows and attempted to knock down the jail door.

Instead, around 11 pm that evening, the sheriff announced that officials would turn Mr. Warner over if the mob would cease the attack on the jail and leave other prisoners unharmed. To prevent “further property damage” to the jail, the sheriff abandoned his duty to protect Mr. Warner from lynching.

Once the mob was permitted to enter the jail, several white men descended upon Mr. Warner, beating, choking and stabbing him. One member of the mob halted the assault on Mr. Warner, stating that he wished to “make this Black boy suffer” before he died. At this request, the mob dragged Mr. Warner down the street, attracting larger crowds that included women and children.

The mob hanged Mr. Warner near the courthouse, then drenched his body with gasoline and set him on fire. Newspapers reported that three children had climbed the tree to fasten the rope that hanged Mr. Warner and, in jumping from the tree, hoisted Mr. Warner’s body in the air. Before Mr. Warner’s body was burned, members of the crowd cut pieces of his leather belt and pants as souvenirs. For two hours, the mob that had by then grown to 7,000 people watched Mr. Warner burn; some witnesses even said that he may have been alive when he was set on fire.

In the wake of Lloyd Warner’s lynching, the white girl he had allegedly attacked reportedly told several newspapers, “they might have gotten the wrong one.”

No one was ever prosecuted or held accountable for the lynching of Mr. Warner. He is one of over 6,500 Black women, men, and children killed in racial terror lynchings in the U.S. between 1865-1950. To learn more about racial terror lynching, read the Equal Justice Initiative’s report, Lynching in America.

Joanna B. Pinneo

On November 29, 1864, American troops murdered more than 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho people who were living peacefully along Sand Creek in eastern Colorado. Days before the massacre, white officials had assured chiefs of the village that their community would not be harmed.

At dawn on November 29, hundreds of U.S. soldiers led by Colonel John Chivington surrounded the village. Residents responded by waving white flags and pleading for mercy; one of the chiefs even raised the American flag in an attempt to demonstrate that he, too, was American. Ignoring these symbols of surrender and peace, the white troops opened fire with carbines and cannons, slaughtering more than 150 Native American people. Most of the victims of the massacre were women, children, and the elderly and infirm. After the massacre, the troops burned the village, mutilated the bodies of the deceased, and removed body parts to keep as trophies. Some scalps of the dead became props in plays that the troops later performed to celebrate, as one soldier boasted, “almost an annihilation of the entire tribe.”

Violence against Indigenous people in the U.S. had been overlooked and ignored for decades. Many white settlers in America cultivated a view that Native people were less human and worthy of dignity and respect than white people. This was evident in the horrific violence and slaughter on display at Sand Creek. Officers tried to justify the massacre by asserting a false narrative that described Indigenous people as less than human, and dangerous, and claimed that the soldiers who committed the massacre had acted in self-defense. This fabricated account was disputed by other American soldiers who witnessed the massacre and felt compelled to tell the truth. “Hundreds of women and children were coming towards us, and getting on their knees begging for mercy,” described U.S. Captain Silas Soule in an 1865 letter to Congress, “[only to be shot] and have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized.”

On November 30, 1921, a mob of white men in Ballinger, Texas, seized Robert Murtore, a 15-year-old Black boy, from the custody of law enforcement and, in broad daylight, shot him to death.

After a 9-year-old white girl alleged that she had been assaulted by an unknown Black boy, suspicion immediately fell on Robert, who worked in the same hotel as the white girl’s mother. He was arrested and held in the Ballinger jail, but word soon spread. On the morning of November 30, a white mob formed outside of the jail in an attempt to lynch Robert. Local law enforcement removed Robert from his cell for transport away from Ballinger; it is unclear whether this was to facilitate or block the lynching.

As the sheriff and Robert drove away from town, an armed mob of white men blocked the road and demanded that the sheriff turn Robert over to them. Though he was armed and charged with protecting Robert while he was in his custody, the sheriff willingly turned the Black teenager over to the mob without a fight.

During this era of racial terror lynchings, it was not uncommon for lynch mobs to seize their victims out of police hands. In some cases, police officials were even found to be complicit or active participants in lynchings. In this case, instead of pursuing the mob to try to stop the lynching or identify the mob members, the sheriff left the mob to its murderous task and rode back to the station at Ballinger to report Robert’s fate.

Unchallenged, the lawless mob seized Robert, drove him to a nearby grove, tied him to a post, and riddled his body with 50 bullets. A Texas newspaper described the mob as “orderly,” leaving “peacefully” after violently taking the young boy’s life.

To learn more about the era of racial terror lynchings, in which thousands of Black people were hanged, shot, mutilated, and drowned, often as law enforcement looked on, read the Equal Justice Initiative’s report, Lynching in America.

Don Cravens

On December 1, 1955, Montgomery, Alabama, police arrested seamstress and activist Rosa Parks for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated city bus. Her stand helped spark the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which remains one of the most well-known campaigns of the civil rights movement. However, Mrs. Parks's work for racial justice long preceded this courageous act. She was very active in the local chapter of the NAACP since joining as the chapter’s only woman member in 1943, and had served as both the youth leader and secretary. Mrs. Parks frequently traveled throughout Alabama to interview Black people who had suffered racial terror, violence, or other injustices. In 1944, she investigated the Abbeville, Alabama, gang-rape of a young Black woman named Recy Taylor, and joined with other civil rights activists to organize a national campaign demanding prosecution of the white men responsible.

On the evening of December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks began her bus ride home from work sitting in the “colored section.” Montgomery’s segregated bus service designated separate seating areas for Black and white passengers; during peak operating hours, if the white seating area became full, the bus driver could expand its boundaries and request that African Americans stand to relinquish their seats to white people. While Black riders were not legally obligated to comply, city bus drivers were notorious for their hostile treatment of Black riders and their requests were rarely refused.

As more white passengers boarded, the bus driver asked Mrs. Parks and three other Black passengers who were seated to give up their seats to white riders. When Mrs. Parks was the only one to refuse, the driver summoned police and she was arrested. Mrs. Parks later recalled that she had refused to stand, not because she was physically tired, but because she was tired of giving in. That same night, Jo Ann Robinson and other local activists began organizing what would become the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

A statue of Mrs. Parks was dedicated in Montgomery on December 1, 2019, near the location where she boarded the bus on the day of her arrest.

On December 2, 1975, a white police officer named Donald Foster shot and killed Bernard Whitehurst Jr., a 32-year-old Black man, after mistaking him for a crime suspect. Rather than acknowledge the mistake, Foster and other officers planted a gun near Mr. Whitehurst’s body as part of an elaborate cover-up of tragic police violence. There was no autopsy report and Mr. Whitehurst’s family was not even notified that he had been killed; they found out about his death shortly after when one family member heard about it on the radio.

Six months after Mr. Whitehurst's killing, an investigation urged by the Whitehurst family revealed that the gun officers claimed had been found near his body had actually been picked up during a drug raid a year earlier. Mr. Whitehurst's body was exhumed soon after and an autopsy confirmed that he had been shot in the back—and not in the chest as the officers who had been chasing him initially claimed.

In 1976, three police officers who had helped plant the gun near Mr. Whitehurst after he was shot were indicted on charges of perjury but only one case went to trial. It resulted in a hung jury. Soon after, the State Attorney General, William Baxley, made a deal with police and government officials that if the officers involved in the alleged cover-up could all pass polygraph tests confirming their innocence, charges against them would be dropped. Rather than take the tests, the city's mayor, the public safety director, and eight police officers resigned or were fired. Mr. Whitehurst’s mother filed a civil suit against the police department but a federal judge ruled that any conspiracy to violate Mr. Whitehurt's civil rights had ended with his death and the jury ultimately returned a verdict in favor of the former police chief, his top aide, and officer Foster. To this day, no one has been held accountable for Mr. Whitehurst’s death.

Jay Dunn for the Salinas Californian

On December 3, 1970, Cesar Chavez was jailed for his refusal to end a boycott on farmers that engaged in coercive, violent, and unjust labor practices against Latino migrant farmworkers. During the summer of 1970, farm owners in California’s Salinas Valley, with the assistance of the Teamsters Union, used coercive tactics to prevent Latino migrant farm workers from joining Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers union. In response, the United Farm Workers union organized a massive strike in the Salinas Valley.

As retaliation for participating in the strike, farm owners fired hundreds of Latino migrant farmworkers and targeted the workers with violence. Striking farmworkers and leaders of the United Farm Workers were attacked and beaten throughout the strike, and in November 1970, the offices of the United Farm Workers in the Salinas Valley were bombed.

As the strike continued, movement leader Cesar Chavez organized a boycott of lettuce produced by farms that had used coercive tactics against the United Farm Workers. The farm owners sought an anti-boycott injunction, which was granted by a Monterey County judge. When Mr. Chavez refused to end the boycott, he was charged with contempt of court for violating the injunction. On December 3, 1970, Judge Gordon Campbell sentenced Mr. Chavez to an indefinite jail term and warned him that “improper and evil methods cannot be used to achieve even noble objectives.”

Cesar Chavez spent 21 days in jail before being released on December 24, 1970. He was held in an isolation cell but received visits from Coretta Scott King, widow of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Ethel Kennedy, widow of Robert F. Kennedy. In early 1971, the California Supreme Court held that the injunction against the strike was unconstitutional, and Cesar Chavez's contempt conviction was overturned.

Around 4:30 am on December 4, 1969, plainclothes officers from the Chicago Police Department armed with shotguns and machine guns kicked down the door of the Chicago apartment where several Black Panther Party members were staying and opened fire on them. Though the Party members were asleep at the time and posed no threat, the officers fired over 90 bullets into the apartment, killing Fred Hampton, 21, and Mark Clark, 22—two leaders of the Black Panther Party—and critically wounding four other Party members. Mr. Hampton had been asleep next to his fiancé, who was eight-months-pregnant when he was killed.

Following Mr. Hampton and Mr. Clark’s assassinations on December 4, seven Panthers at the apartment that night, who had allegedly wounded two officers, were charged with attempted murder. In a statement released after the shooting, Edward Hanrahan, the Cook County state’s attorney who had ordered the violent raid, said: “The immediate, violent, criminal reaction of the occupants in shooting at announced police officers emphasizes the extreme viciousness of the Black Panther Party.”

Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale formed the Black Panther Party for Self Defense in Oakland, California, in 1966. Spurning civil rights tactics of marches, sit-ins, and boycotts, the Black Panther Party was inspired by the self-determination philosophy of Malcolm X and the “Black Power” speeches of Kwame Ture (born Stokely Carmichael). The Party founded youth centers and free breakfast programs, organized legally-armed patrols to guard against police brutality in Black neighborhoods, and became popular among Black urban youth as chapters spread throughout the country. In the 1968-69 school year, the Black Panther Party fed as many as 20,000 children.

Despite their goals of community empowerment and self-help, the Party was condemned by President Lyndon B. Johnson and other national leaders. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover called the group “the most dangerous threat to the internal security of the country” in the late 1960s. The FBI also launched an aggressive counter-intelligence program aimed at dismantling the Black Panther Party through misinformation, infiltration, and by facilitating violent attacks against the group.

Just four days after the Chicago shooting, on December 8, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) violently raided the Black Panther Party’s headquarters in Los Angeles, California. In 1968, as urban riots were spreading across the country in response to police brutality, the Southern California Chapter of the Black Panther Party formed to help combat the growing threat. The Party established monitoring patrols in Black neighborhoods and worked to ensure police accountability.

On December 8, the LAPD set out to serve a warrant to search Party headquarters at 41st Street and Central Avenue for stolen weapons. Though the warrant was obtained using false information provided by the FBI, police used it as the basis to ambush about twelve Party members inside the building. More than 200 police officers, including the newly militarized Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) team descended on the headquarters, armed with 5,000 rounds of ammunition, gas masks, a helicopter, a tank, and a military-grade grenade. During the coordinated attack, three officers and six members of the Black Panther Party were wounded.

LAPD officers arrest Black Panther Party members during a raid on December 8, 1969.

In 1976, five years after the FBI’s counterintelligence program was shut down, a Senate committee concluded that the bureau’s tactics “were indisputably degrading to a free society” and “gave rise to the risk of death and often disregarded the personal rights and dignity of the victims.”

The Washington Times

On December 5, 1910, Chief Justice Shepard of the District Court of Appeals in Washington D.C., ruled that Isabel Wall, an eight-year-old girl, was prohibited from attending the local white public school because she was 1/16th Black. The court held that any child with an “admixture of colored blood” would be classified as such; thus, Isabel would be made to attend a separate school for Black children.

The decision in Oyster v. Wall came just over a decade after the Supreme Court’s ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which held that the U.S. Constitution permitted the racial segregation of public facilities. Isabel’s parents filed a lawsuit against the D.C. School Board objecting to the law providing for segregated schooling, but also arguing that, even if segregation was appropriate, their child was not Black.

Growing up, Isabel had been “treated and recognized by her neighbors and friends” as white, according to court filings. The School Board, however, refused to admit her into Brookland White School on account of her “blood,” which they believed made her ineligible to attend school with white students.

Justice Shepard sided with the School Board and ruled that, if “the child is of negro blood of one eighth to one sixteenth; that her racial status is that of the negro.” His decision asserted that “no matter what the complexion,” any person who has “an appreciable admixture of negro blood” would be considered “colored.” Justice Shepard ruled that physical characteristics of an individual were irrelevant as “the sense of sight is but one avenue for the conveyance of information upon the subject of racial identity to the mind of the investigator.” Justice Shepard’s decision thus relied on bigoted views of racial groups, and suggested that even where Black ancestry was not easily detectable in someone’s physical appearance, Blackness manifested itself in racial “traits.”

Justice Shepard acknowledged the disparities in the quality of education and funding between schools attended by white students and schools attended by Black students, as well as the fallacy of “separate but equal.” He knew that Isabel Wall, like all other Black students, would be greatly disadvantaged in the quality of education she could receive at the underfunded segregated school. Justice Shepard even recognized that as a “cruel hardship,” but justified the decision by insisting it would be a “greater evil” to allow a child with even one Black great-great-grandparent to attend a white school.

Read the Oyster v. Wall decision here.

Library of Congress

On December 6, 1915, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a decision upholding the Expatriation Act of 1907, which stripped American women of their citizenship when they married a non-citizen. Under that act, women who lost their U.S. citizenship could apply to be naturalized if their husbands later became American citizens—but since virtually all Asian immigrants were legally barred from becoming U.S. citizens at the time, an American woman who married an Asian man would lose her citizenship permanently. Similarly, women of Asian descent who were American citizens by birth had no means of regaining their U.S. citizenship if they lost it through marriage to a foreigner—even if the foreigner was white—because Asian men and women were ineligible for naturalization in all circumstances.

Meanwhile, American men who married foreign women were permitted to keep their citizenship.

Mackenzie v. Hare was an attempt to challenge the Expatriation Act and reached the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court upheld the law, ruling that an involuntary revocation of citizenship would be unconstitutional, but stripping a woman of citizenship upon marriage to a foreign husband was permissible because such women voluntarily enter into such marriages, “with knowledge of the consequences.”

The Expatriation Act remained in full effect until 1922, when Congress amended the law to permit most women to retain their American citizenship after marriage to a non-U.S. citizen—but still stripped citizenship from American women married to Asian immigrants ineligible for citizenship until discriminatory immigration laws were reformed in the 1960s. In 2014, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution expressing regret for the past revocation of American women's citizenship under this law.

The Inter Ocean (Chicago)

On December 7, 1874, white mobs attacked and killed dozens of Black citizens of Vicksburg, Mississippi, who had organized a political meeting in support of a duly elected Black sheriff, who had been improperly removed from office.

During the Reconstruction era that followed Emancipation and the Civil War, Black Mississippians made progress toward political equality. Despite the passage of Black Codes designed to oppress and disenfranchise Black people in the South, under the protection of federal troops in place to enforce the newly established civil rights of Black people, many Black men voted and served in political office on federal, state, and local levels.

In the 1870s, Peter Crosby, a formerly enslaved Black man, was elected sheriff in Vicksburg, Mississippi—but shortly after taking office, Sheriff Crosby was indicted on false criminal charges and a violent white mob removed him from his position.

On December 7, 1874, Black citizens in Vicksburg organized an effort to try to help Mr. Crosby regain his office. In response, white mobs attacked and killed dozens of Black citizens in an act of racial terrorism, which would later become known as the “Vicksburg Massacre.”

Following this brutal attack, federal troops were sent to Vicksburg and Mr. Crosby was appointed as sheriff again. However, in early 1875, a white man named J.P. Gilmer was hired to serve as Sheriff Crosby's deputy. After Sheriff Crosby tried to have Mr. Gilmer removed from office, Mr. Gilmer shot Sheriff Crosby in the head on June 7, 1875. Mr. Gilmer was arrested for the attempted assassination but never brought to trial. Mr. Crosby survived the shooting but never made a full recovery, and had to serve the remainder of his term through a representative white citizen.

The violence and intimidation tactics utilized by white Mississippians intent on restoring white supremacy soon enabled forces antagonistic to the aims of Reconstruction and racial equality to regain power in Mississippi.

Learn more about the history of racial violence during Reconstruction and how it was used to suppress political reform and hinder Black political development.

On December 8, 1915, a white mob in New Hope near Columbus, Mississippi, raped and lynched a Black woman named Cordelia Stevenson and left her body hanging for days near a railroad track to terrorize Black residents.

Several months earlier, the barn of a white man named Gabe Frank burned down, and the town quickly focused suspicion on Black community members, including Mrs. Stevenson’s son. The deep racial hostility that permeated Southern society during this time period often served to focus suspicion on Black communities after a crime was discovered or alleged, whether evidence supported that suspicion or not. Though Mrs. Stevenson insisted that her son had moved out of town months before the barn burned, and though no evidence tied him to the fire, local authorities seized Mrs. Stevenson and her husband, Arch, for questioning.

The local police ultimately concluded the Stevensons’ son had not been involved in the barn fire, and released them both. Soon after, on December 8, a white mob gathered outside the Stevenson home, forced their way into the house while the couple slept, and kidnapped Mrs. Stevenson. The mob raped and lynched her, then left Mrs. Stevenson’s naked, brutalized body hanging by the railroad track for two days, where she was visible to thousands of people traveling by train.

No one was ever held responsible for her death.

Cordelia Stevenson was one of at least 20 victims of racial terror lynching killed in Lowndes County, Mississippi, and one of at least 655 Black people lynched in Mississippi between 1877 and 1950. To learn more, read the Equal Justice Initiative’s report, Lynching in America.

John Moore, AP

On December 9, 2014, the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence released a report revealing the CIA’s use of torture against Muslim detainees during the “War on Terror.” The report detailed dozens of horrific accounts of Muslim people being dehumanized to such an extent that they were likened to “dogs who had been kenneled.”

The story of Gul Rahman is illustrative of what the Senate Select Committee uncovered about the CIA’s practices between 2001 and 2006. In November 2002, Mr. Rahman was subjected to “48 hours of sleep deprivation, auditory overload, total darkness, isolation, a cold shower, and rough treatment.” Immediately following this experience, he was labeled as “uncooperative,” stripped of his clothing, shackled to the wall of his cell, and “forced to sit on the bare concrete floor without pants.” His autopsy revealed that he most likely died from hypothermia. Three months after Mr. Rahman froze to death, the CIA approved a plan to strip detainees nude in rooms set to near freezing temperatures. No officials were charged for Mr. Rahman’s death, and one of his interrogators was recommended to receive a $2,500 bonus for his “consistently superior work.”

In addition to exposing stories similar to Mr. Rahman’s (including accounts of people being subjected to force-feeding, mock executions, and sexual violence), the report concluded that the CIA had misled Congress about its practices, under-reported the number of people it had detained and tortured, and falsely incarcerated more than 20% of its detainees. One of the people unlawfully detained was an “intellectually challenged” man who was used as “leverage” to obtain information from a family member. Despite these troubling findings, there have been few attempts to hold anyone accountable for the harm that U.S. officials perpetrated against Muslim detainees.

Humboldt State University

On December 10, 1960, Black college football players from California's Humboldt State College were banned from "mixing" with white people during their stay in Florida for the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) National Championship Football Game. After an undefeated season, the racially integrated team earned the right to compete in the Holiday Bowl on December 10 in St. Petersburg, Florida, for the national title. However, segregated facilities forbade Humboldt State’s Black players from sleeping under the same roof as their white teammates.

The 1960 Holiday Bowl in St. Petersburg brought together the Humboldt State Lumberjacks team and the all-white Lenoir-Rhyne University Bears from North Carolina. The five Black players who traveled to Florida as part of the Lumberjacks team—fullbacks Dave Littleton, Earl Love, and Ed White; tackle Vester Flanagan; and guard Walt Mosely—were denied entrance to the hotel where their white teammates were permitted to stay.

As in most cities across the South, St. Petersburg’s Jim Crow laws stringently defined and dominated all aspects of life from the major to the mundane. Segregation laws barred any “race mixing” in public hospitals, schools, transportation, and other public accommodations. Due to these policies, Black men, women and children experienced the daily humiliation of a system designed to maintain racial hierarchy and uphold white supremacy.

Even in 1960, college football remained segregated throughout the South, largely because colleges and universities in the region remained segregated. Though the U.S. Supreme Court struck down school segregation in its 1954 decision, Brown v. Board of Education, Southern lawmakers' defiant resistance to that decision greatly delayed implementation; by 1960, flagship state schools in Alabama and Mississippi had not yet allowed a Black student to enroll, and Southern white schools achieved all-white athletic competition by segregating themselves into all-white athletic conferences. This meant that Black athletes living in the South were restricted to attending and playing for Historically Black Colleges and Universities in segregated conferences within the region, or relocating to play at integrated schools in the North and West.

Integrated and segregated schools still met in competition when paired in bowl and national title games; and when they did, racial prejudice was pervasive. The all-white University of Alabama football team refused to play any integrated teams for years, until it accepted a bid in the 1959 Liberty Bowl against Penn State and lineman Charley Janerette became the first Black player to face the Crimson Tide (Penn State won, 7-0). Just one year later, the NAIA arranged a national title game to take place in Florida, and Humboldt State’s Black players received virtually no support from the athletic conference or their school administrators.

Despite calls from some students and organizers that humiliating Black players to submit to racist segregation requirements was unacceptable, players were nonetheless compelled to play. Humboldt State’s head coach, Phil Sarboe, praised the treatment the team had received in St. Petersburg, denied that players were unhappy about the segregated facilities, and expressed that Humboldt State would “like to come back next year.”

To learn more about the era of segregation in the U.S., read the Equal Justice Initiative’s report, Segregation in America.

On December 11, 1917, the U.S. Army executed 13 Black soldiers who had been previously court-martialed and denied any right to appeal. In July 1917, the all-Black 3rd Battalion of the 24th United States Infantry Regiment was stationed at Camp Logan, near Houston, Texas, to guard white soldiers preparing for deployment to Europe. From the beginning of their assignment at Camp Logan, the Black soldiers were harassed and abused by the Houston police force.

Early on August 23, 1917, several soldiers, including a well-respected corporal, were brutally beaten and jailed by police. Police officers regularly beat African American troops and arrested them on baseless charges; the August 23 assault was the latest in a string of police abuses that had pushed the Black soldiers to their breaking point.

Seemingly under attack by local white authorities, over 150 Black soldiers armed themselves and left for Houston to confront the police about the persistent violence. They planned to stage a peaceful march to the police station as a demonstration against their mistreatment by police. However, just outside the city, the soldiers encountered a mob of armed white men. In the ensuing violence, four soldiers, four policemen, and 12 civilians were killed.

In the aftermath, the military investigated and court-martialed 157 Black soldiers, trying them in three separate proceedings. In the first military trial, held in November 1917, 63 soldiers were tried and 54 were convicted on all charges. At sentencing, 13 were sentenced to death and 43 received life imprisonment. The 13 condemned soldiers were denied any right to appeal and were hanged on December 11, 1917.

The second and third trials resulted in death sentences for an additional 16 soldiers; however, those men were given the opportunity to appeal, largely due to negative public reactions to the first 13 unlawful executions. President Woodrow Wilson ultimately commuted the death sentences for 10 of the remaining soldiers facing death, but the remaining six were hanged. In total, the Houston unrest resulted in the executions of 19 Black soldiers. NAACP advocacy and legal assistance later helped secure the early release of most of the 50 soldiers serving life sentences. No white civilians were ever brought to trial for involvement in the violence.

Tampa Bay Times

In December 1922, a mob of more than 1,000 white people lynched two Black men in Taylor County, Florida.

On December 2, 1922, a white schoolteacher was found killed in Perry, Florida. Though items found near the woman’s body belonged to a local white man, police insisted the perpetrator had to be a Black man and quickly focused on a Black man named Charles Wright as a suspect. The deep racial hostility that permeated Southern society during this time period often served to focus suspicion on Black communities after a crime was discovered, whether evidence supported that suspicion or not. This was especially true in cases of violent crime against white victims.

After several days of violent manhunts that terrorized the Black community and left at least one Black man dead, police arrested Charles Wright with a friend named Arthur Young. Before the men could be investigated or tried, a white mob seized Mr. Wright as they were being transported to jail and burned him alive.

Four days later, on December 12, the lynch mob attacked again. As officers were moving Arthur Young to another jail, the white mob seized him, riddled his body with bullets, and left his body hanging from a tree on the side of a highway in Perry, Florida.

The public lynching of Arthur Young, like that of Charles Wright, was not only intended to inflict harm on these individual men; it was also meant to terrorize the entire Black community. Following these murders, members of the mob turned on the Black community of Perry, burning several Black-owned homes, a church, the Masonic hall, and a school. Dozens of Black families fled the area, moving to the North as refugees from racial violence. No one was ever held accountable for the lynchings of Arthur Young and Charles Wright. They are among 15 documented African American victims of racial terror lynching killed in Taylor County, Florida, between 1877 and 1950.

On December 13, 1893, Judge Householder of Knoxville, Tennessee, sent an entire family to jail on felony miscegenation charges. Setting bond at $500, he jailed a Black man named Jim McFarland, and his mother, Ms. McFarland, a Black woman, Henry Whitehead, a Black man, Harriet Smith, who newspapers and local authorities reported was a white woman, and her children from prior relationships with white men, Lydia Smith and John Smith. At the time of arrest, the multigenerational family lived in the same household. The court’s order left a young child at home without a caregiver. The family spent over a month in jail before facing trial in January.

Newspapers at the time noted that Ms. Smith had reported to them “with shameless candor,” that she was actually a Black woman—while her mother was white, her father was a light-skinned Black man—and that she had never pretended to be white. Local news speculated further that since Ms. Smith’s children had white fathers, those children living with Black men and women might violate the miscegenation codes as written “even should the taint of negro blood be traced to the remote degree claimed.”

Local media praised Squire Householder’s actions, reporting that he “came to the rescue of the community” by “starting a war on the crime of miscegenation.” The white community in Knoxville universally commended the judge’s decision to incarcerate the family. White citizens viewed the case as an opportunity to expand the reach of a state law criminalizing relationships between Black and white people. While Tennessee law classified interracial marriage as a felony, at the time of the family’s arrest, no state supreme court decision addressed whether interracial cohabitation was a felony or a misdemeanor. The press and the courts hoped to eliminate interracial relationships entirely by terrorizing interracial couples with the threat of extreme punishment. As the Knoxville Sentinel wrote:

"There is no crime so common in Knoxville as white people living together with [Black people], and to make the matter more revolting, it generally happens that it is a white woman living with a [Black man].... These [Black men] and their white mistresses will soon abandon their loathsome relations when they find that they must go to the penitentiary if they continue to live together."

Ultimately, a month after her arrest, Ms. Smith was tried before a jury that determined she was “of colored stock,” and acquitted her and Henry Whitehead of miscegenation. However, the jury still convicted them both of lewdness for living together, and they were each sentenced to 11 months in the workhouse. The cases against her children were dropped by the prosecutor after this verdict.

To learn more about anti-miscegenation laws and other laws that denigrated the humanity of Black people, read EJI’s report, Segregation in America.

No comments:

Post a Comment