~~ recommended by emil karpo ~~

Editor’s note: This is an edited excerpt from Megan Asaka’s book “Seattle from the Margins: Exclusion, Erasure, and the Making of a Pacific Coast City,” published in September by the University of Washington Press.

THE HISTORY OF HOPS in the Pacific Northwest begins with water. Though agriculture is often understood as a solely land-based endeavor, Puget Sound waterways played a crucial role in the emergence of this particular regional industry. Though Puget Sound provided the cities and towns dotting its shoreline with access to the Pacific Ocean, its rivers and tributaries served an equally useful purpose: linking small inland towns with coastal communities across Western Washington.

Seattle stood at the heart of this vast marine space. Situated at the convergence of multiple rivers, the lands that would become known as Seattle served as a crucial hub of Indigenous migrations. Though the city was located within Duwamish territory, other Indigenous peoples up and down the Northwest Coast also had a presence in Seattle, whether for travel, resource gathering or connecting with extended family. These migrations did not stop with the arrival of white settlers and the disruptions of urban displacement. Seattle’s role as “the place where one crosses over” persisted into the late 19th and early 20th centuries and beyond.

Chinese histories in the Pacific Northwest also revolved around water. Many of the early Chinese migrants came to Seattle through Vancouver, B.C., traversing the waters of the Salish Sea as they crossed into the United States from Canada. Chinese laborers also worked aboard steamships that sailed through Puget Sound, including those that carried lumber to markets around the region and down to California. Though their connection to the Salish Sea was very different, they shared with their fellow Indigenous migrants a maritime world that brought them frequently to Seattle.

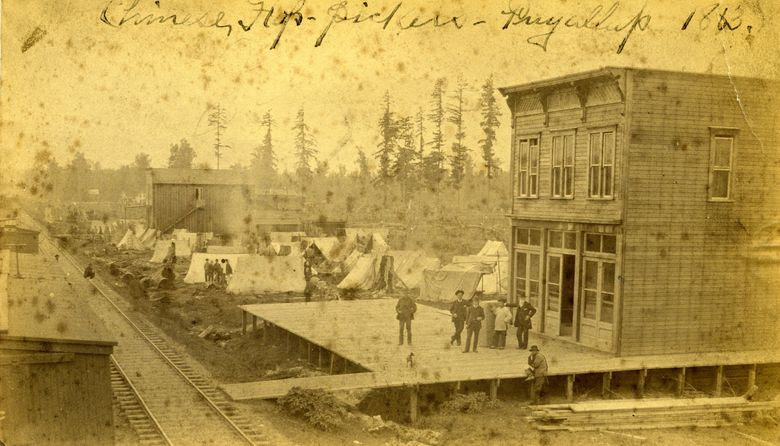

The concentration of Indigenous and Chinese migrants in Seattle established the city as an early hub of labor migration. Their maritime mobility and accessibility made them a desirable source of labor for employers across the region, which lacked a railroad system until the late 19th century. Hop growers, many of them settlers who established farms on the rivers and tributaries of Puget Sound, utilized these urban-based maritime networks, often traveling to Seattle to hire their seasonal workforce.

Hops, the main ingredient used for flavoring beer, arrived in the Pacific Northwest in the 1860s and soon emerged as the region’s first major agricultural industry, in large part because of the availability of Indigenous and Chinese labor. Though the Klondike Gold Rush of 1897 looms large in local historical memory as the key event that shaped Seattle’s regional connections, the miners and adventurers who passed through the city on their way up north were traversing routes that long had been established by Indigenous and Chinese migrants.

The concentration of these two groups in the same city, within the shared space of the south end and waterfront district, appealed strongly to employers. Chinese and Indigenous migrants had a presence in many urban coastal areas across the Pacific Northwest during this time, but it was only in Seattle that the two were pushed so closely together.

In Seattle, employers had access to both groups and could hire one or the other, or both, at the same time. This gave hop growers, in particular, the flexibility they needed to accommodate the unpredictable nature of the hop harvest. It also allowed them to exploit divisions between the two in order to depress wages and maintain a profit margin. Though scholars tend to treat Indigenous and Chinese laborers as inhabiting almost separate worlds, their proximity and interconnection made the regional economy possible.

This city-based employment system, though, did not always work as growers anticipated. The maritime world of the Puget Sound region allowed for a kind of autonomy among the workforce that continually undermined growers’ expectations of a smoothly functioning industry. It brought people together in unpredictable ways, leading to new forms of sociability and leisure as well as conflicts and violence. As Seattle’s role as a hub of labor migration expanded, this unpredictability intensified; it would plague employers, industry leaders and politicians well into the 20th century. In this way, the hops industry set the stage for future industrial expansion, while also exposing the system’s inherent fragility and the stark limitations of settler power.

SEATTLE IN 1870 was still a relatively small city, its population hovering around 1,000 residents. With an official incorporation date of 1869, Seattle also was a very new city.

At that time, the urban economy still revolved mostly around settler Henry Yesler’s sawmill, which sold cut timber to other settler communities around Puget Sound, as well as in California. The commercial and entertainment district surrounding the mill, known as the Sawdust, provided another source of economic activity, attracting people from beyond the city and generating revenue from customers far and wide.

Indigenous and Chinese laborers constituted the bulk of the urban workforce then, toiling in the sawmill and construction projects as well as performing domestic labor such as laundry and housekeeping.

Seattle remained stratified by race, reflecting settlers’ efforts to claim and occupy Indigenous lands by creating a northern residential district for white families and policing racial and gender boundaries through municipal regulation. These practices also consolidated workers in one geographic area, which benefited employers, including hop growers, who could more easily access this pool of labor. Seattle’s urban context of racial segregation and displacement thus played a key role in Puget Sound hop growers’ employment practices, as well as the city’s growth as a regional hub.

Seattle’s position within the marine space of the Puget Sound area made it an ideal place for Indigenous workers to converge before the harvest season. Seattle long had served as a “crossing-over place” for Puget Sound Coast Salish peoples. As more Indigenous people from along the Northwest coast, including Alaska, joined the hop-picking workforce, they included a stopover in Seattle.

Sightings of their canoe fleets signaled the start of hop-picking season and were widely covered in the Seattle press. In 1879, a local journalist noted, “The bay and its shores were dotted and lined with their canoes, while the store fronts and sidewalks downtown were thick with the Indians themselves.” Another report described the waterfront during hops season as “crowded with rudely constructed tents and other hastily built habitations.” Many camped along the shore for days, often with their children and families, cooking and socializing with one another before heading out to the harvest.

Though some commentators described these multitribal waterfront gatherings as “strange” and “striking,” Indigenous movement through this area long had predated the city itself and would continue even after the decline of the hop industry.

IN ADDITION TO social gatherings, Indigenous workers used their time in Seattle to shop and engage in other commercial activities. Before the harvest, they often focused on purchasing food, clothing and other supplies for the three-week picking season, while after the harvest, they indulged in less practical goods to take back home, such as cufflinks and handbells. Their presence and purchasing power created a legitimate sensation among local businesses and shopkeepers.

Not confined to the shore and waterfront camps, Indigenous shoppers ventured into the commercial district, purchasing “anything which may attract their attention in store windows,” according to one account. Other vendors and merchants came directly to them, like one “enterprising” salesperson who “spread his goods on boxes outside, and has done on the side-walk a rushing business with Indians returning flushed with money from the hop-yards.”

Front Street (now First Avenue), which ran along the waterfront near Yesler’s sawmill, received the most traffic. Its shops offered goods and services ranging from banking to billiards, jewelry to tailoring, cigars, hardware and candy. Indigenous hop pickers also took the opportunity to vend their own goods to local Seattleites. One newspaper described the popularity of “woven baskets and large rugs” sold by Indigenous women in the commercial district.

IT WAS DURING this time that hop growers traveled up to Seattle to recruit pickers camped along the waterfront. Once growers had decided to scale up and look beyond the local towns for their workforce, hop picking took on a life of its own among Coast Salish and other Northwest Coast Indigenous communities, becoming one of the most popular forms of wage labor. “The reservation has been quite deserted during the last month,” wrote a missionary on the Tulalip Reservation in 1882, “the Indians nearly all gone hop picking.”

No comments:

Post a Comment