punishing-the-criminalized-sector-of-the-working-class/

NB note - please refer to the link above for the footnotes to this article.

AFTER SIX AND a half years in Federal and state prisons in California, in May of 2009 I paroled to Illinois to be with my family. On my second day home, a bubbly white woman from the Department of Corrections showed up and strapped a black plastic band to my ankle — a GPS monitor.

I wasn’t worried about that plastic band. Surveillance was nothing new to me. I had spent 27 years as a fugitive with my wanted posters on post office walls. In prison, authorities watched my every move, either through cameras, the guard towers, or their spies in the incarcerated population.

The band would be no different. It wasn’t a cage. I was free.

The next day my parole agent phoned, “You’ll only be allowed out of the house Monday through Friday from 6 a.m. to 10 a.m.” Those visions I had of freedom while lying on my prison bunk vanished. He had turned my safe space into a carceral space and made my loved ones into prison staff.

From that moment on, I took on the project of researching electronic monitoring. Who made up the rules for these devices? Who was making money from them?

Eventually I connected a lot of those dots. Through gathering the stories of other folks who had been on the monitor, and doing research as the director of the Challenging E-Carceration campaign at MediaJustice, I developed a much richer understanding of a technology that I now refer to as an ankle shackle, part of the realm of e-carceration.

While I’ve been doing this research, these technologies have marched onwards. Today, a little more than a decade later, the vast majority of the population has a smart phone with a GPS tracking device that they leave turned on. They download apps like Google Maps and The Weather Channel which rely on tracking to provide data to the user.

Being tracked has become normalized. People born after the year 2000 may have never experienced a moment in their lives when they were not being digitally tracked.

Many people refer to this as a surveillance state. Some refer to it as mass supervision. I choose the term e-carceration to emphasize how all these technologies actually perform the basic function of incarceration — depriving us of our liberty.

In the excerpt below from my book, I briefly describe e-carceration and how it differs from brick and mortar incarceration. I also describe a few of the technologies involved.

Dynamics of E-carceration

For socialists and anti-capitalists of all stripes, understanding the dynamics of e-carceration, or whatever you may choose to call it, is important for at least three reasons.

First, they center the driving forces of monopoly capitalism of this era.

In early industrialization, we had the robber barons of oil and steel leading the way, accompanied by imperialist resource plunderers like the British East India Company and Compagnie du Congo Belge.

The new robber barons Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Sundar Pichai, Tim Cook come out of what is popularly known as Big Tech. They are not just wealthy computers nerds. They are building major portions of infrastructure within which capitalism operates.

Like classical colonialists they have “discovered” uninhabited, unused space, the digital world, and claimed it as their own. They determine the frameworks of the space, the rules of the space, and they find more and more ways to extract profit from the space.

A significant source of that profit comes from data that we own — data derived from surveilling our daily activities usually without our permission, often without our knowledge. We all play on their internet playing field, using their software and hardware.

We may benefit and improve parts of our lives by playing this game, but at the same time we feed our own destruction, contributing to our own deprivation of liberty via the data we surrender.

Like labor power, that data belongs to us but is appropriated by profiteers. Ultimately it can be weaponized through algorithms and risk assessments to block us from access to housing, employment, health care.

Just as in all capitalist configurations, but especially in a colonial setting, weaponization is selective. The marginalized sectors of the working class and the rural poor are always the primary targets for exploitation, e-carceration and exclusion.

We often think of the forces behind the technologies of e-carceration as inhabiting a digital world detached from a material reality, the brick and mortar, concrete and steel of the industrial revolution. But as much as they try to hide it, the purveyors of e-carceration, the owners of tech capital rely on the exploitation of labor and land — from young boys digging for coltan in the Congo, to the setting aside of land to host cloud server campuses, to the millions of workers delivering and servicing their operations.

Amazon has 1.468 million workers along with 33% of the $180 billion-a-year, cloud-computing sector. Their digital world cannot exist without the exploitation of labor.

Alternative Possibilities

Second, the evolution of technology as driven by the contemporary robber barons offers a constant reminder of what this technology could do if driven by popular not profit-making interests. Those of us who operate out of the paradigm of abolition, as well as being socialists, recognize that abolition is not simply about tearing down the existing system but imagining something new.

Just as enslaved people in the United States in the 1860s imagined an end to plantation exploitation, so too did they imagine themselves as landowners and decision-makers. The abolitionist imaginary cannot simply be a fluffy vision of peace. Rather, that reality can only be the culmination of a long political struggle led by those I refer to in my book as the criminalized sector of the working class, that disproportionately Black, brown, Indigenous and LGBTQ+ population.

We need to spend just as much time imagining the struggle to capture the means of digital production, and the type of organization needed to carry out that struggle, as we spend imagining the post-Bezos world.

Understanding and Action

(The following is an excerpt from Understanding E-Carceration by James Kilgore, The New Press, 2022. It is reproduced below with the permission of the author.)

“Many of the current reform efforts contain the seeds of the next generation of racial and social control, a system of ‘e-carceration’ that may prove more dangerous and more difficult to challenge than the one we hope to leave behind. . . . Some insist that [this system] is ‘a step in the right direction.’ But where are we going with this?” —Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow.(1)

Black Liberation organizer and media justice visionary Malkia Devich-Cyril introduced the term “e-carceration” in 2015. Devich-Cyril defines e-carceration as mass incarceration blended with the technology of electronic surveillance and punishment.(2)

Since Devich-Cyril introduced this term, three important things have happened. First, e-carceration has become equated largely with only electronic ankle monitors, narrowing our vision and capacity to assess the challenges we face from these technologies of oppression. Second, the emergence of new technologies and rapid expansion of what existed in 2015 has dramatically changed the scale of the e-carceration Devich-Cyril first defined.

Third, the technologies of e-carceration are becoming normalized within our contemporary political economy. Today we can think of e-carceration more broadly as the application of a network of punitive technologies to social problems.

Ultimately, these technologies deprive people of their liberty. They do this through confinement, tracking, and recording a range of movements, activities, and even bodily functions. Sometimes, this extends to entire communities or social movements.

The most well-known form of e-carceration is house arrest with an ankle monitor, but new technologies of e-carceration are emerging every day. They include facial recognition software, license plate readers, closed-circuit TV (CCTV) cameras, drones, and social media monitors.

Of central importance among these technologies are risk assessment tools, which are mathematically based formulas often used by the criminal legal system and other government agencies to determine whether or not a person should be incarcerated or surveilled.(3)

Although many of these technologies at first glance may appear to be neutral and not punitive or harmful, when applied in conjunction with criminal legal and repressive immigration policies within a neoliberal economic framework, they inevitably contribute to deprivation of liberty.

How E-carceration is Different

E-carceration deprives people of their freedom but not through physical confinement as applied in places like prisons, jails, immigration detention “centers,” and lockup mental health facilities.

Four main differences distinguish e-carceration. First, e-carceration often may deprive a person of their liberty by denying them access to resources such as employment, housing, medical treatment, therapy, or the opportunity to spend time with their loved ones.

This deprivation of liberty often occurs through the weaponization of data. This involves using a range of information stored in various databases to create a profile that rates a person’s eligibility to access certain social services.

These ratings can even determine whether or not a person should be imprisoned. The eligibility rating may be deeply influenced by several factors including a person’s race, age, gender/gender identity, disability, religion, immigration status, and national origin.

Second, the punishment of e-carceration is not always time bound by a sentence or period of carceral control such as parole or probation. If it involves the collection and storage of data, the punishment or harm done by this technology may have no time boundaries.

This particularly applies when e-carceration involves medical interventions such as what researcher Erick Fabris refers to as “tranquil prisons” that involve forced treatment orders and mandatory medication.(4)

Fabris, who is a survivor of the psychiatric punishment system and a co-founder of Psychiatric Survivor Pride Day, emphasizes how medications may deprive people of their liberty by reducing their cognition or ability to communicate.

Third, in some instances, the technology of e-carceration is administered without a person’s explicit knowledge or permission. While an individual definitely knows if they are in a jail cell or on an ankle monitor, they may not be aware when they are subject to e-carceration technologies such as facial recognition and drones.

Among other things, these technologies have the capacity to select and target individuals in a crowd. For example, during the early 19 days of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, Chinese authorities introduced drones with facial recognition capacity to identify people who weren’t wearing masks.

Police in U.S. cities have used facial recognition to identify and arrest protesters who they allege have broken the law. One of the most publicized incidents occurred in 2020 when Donald Trump cleared the streets to stage a photo op of him holding a Bible in front St. John’s Episcopal Church in Washington, DC.

Michael Peterson, who was taking part in a Black Lives Matter protest near the church at the time, was later arrested after being photographed in a scuffle with police during the street clearing. To match Peterson’s face, police used a national database called National Capital Region Facial Recognition Investigative Leads System, then scoured Twitter to track him down.(5)

New York BLM leader Derrick Ingram was arrested on an assault charge after facial recognition supposedly identified him as the person who shouted into the ear of a police officer with a bullhorn. Facial recognition also featured in the identification of those involved in the coup attempt of January 6, 2021.(6)

Fourth, people may be directly complicit in the intensification of their e-carceration. They may do this by adding data and information to databases used to predict behavior and authorize official responses or by not protecting themselves from such data captures.

The simple act of providing personal details for an online purchase or downloading the many apps that have location tracking capacity exemplify this sort of unconscious complicity. The popular Weather Channel app, which informs users they are gathering location data, has faced lawsuits for selling that data to private companies.

Even Muslim prayer apps such as Salaat First (which has more than 10 million downloads) and Muslim Pro have been discovered to be tracking location.(7)

Pressures for Reform

The expansion of e-carceration is the result of two forces in tension: popular mobilization against mass incarceration, and the drive for profitability.

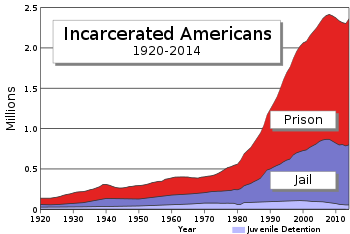

The late 2000s saw the emergence of a wide range of critiques of and organized opposition to mass incarceration. Much of this focused on the War on Drugs. Civil rights lawyer Michelle Alexander’s 2010 book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, spent more than 250 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list.

This work highlighted measures that led to the rise of the prison population, including drug policies that disproportionately impacted Black people, and the enduring consequences that a prison sentence levies on people once they are released.(8)

Alexander’s writings, along with pressure from national advocacy organizations such as the Drug Policy Alliance to moderate drug sentencing laws, ultimately reached the highest levels of government. In 2015, Barack Obama became the first president to ever visit a prison and used the opportunity to commute the sentences of forty-six people who had spent many years in prison, many for nonviolent drug offenses.

Obama’s criminal justice platform stressed the racial inequities in the system and the need for more effective reentry programs.(9) His attorney general Eric Holder condemned “widespread incarceration” as “both ineffective and unsustainable,” and ordered a rollback in enforcement of some federal drug laws.(10)

At state and local levels, community-based activism blossomed, targeting the excessive expenditure on prisons and jails, racialized police violence, and the need for bail reform. In many of these struggles, radical voices led the way, often from people who were survivors of incarceration themselves.

Activist-philosopher Angela Davis, a political prisoner in the 1970s, was among the leaders calling for a more radical agenda, including the abolition of prisons. This growing mobilization against mass incarceration overlapped with the meteoric rise of nationwide protests against the police murders of unarmed Black people such as Michael Brown, Eric Garner and Sandra Bland.

The newly emerging formation Black Lives Matter, founded by three Black women, Patrisse Cullors, Opal Tometi and Alicia Garza, became the largest organized voice in decades for racial and gender justice. The growth of these social justice movements forced many people in the law-and-order camp to moderate their views.

Former speaker of the House of Representatives Newt Gingrich, a Republican and long a staunch supporter of the “lock ’em up and throw away the key” approach, formed the conservative, reform-minded campaign Right on Crime in 2007.

Gingrich and his cohort spoke of an “urgent need” to reduce the prison population and argued that “conservatives must lead the way (in) fixing the system.” Gingrich’s change of heart apparently reflected a deep-rooted soul-searching: “Once you decide everybody in prison is also an American then you gotta really reach into your own heart and ask, is this the best we can do?”(11)

E-carceration for Profit

These shifts in viewpoint among both Democrats and Republicans sparked debates about measures to reduce the prison population. The economic crisis of 2008 put further pressure on lawmakers to reduce expenditure on the criminal legal system.

One result was an exploration of “alternatives to incarceration,” ways to handle people who broke the law without resorting to prison or jail.

These alternatives, which included forms of e-carceration such as electronic monitoring, reflect what I have labeled “carceral humanism,” the re-packaging of methods of social control and punishment as the delivery of caregiving services. This reform process had economic ripple effects, prompting those who had financially benefited from mass incarceration to explore new avenues of gaining revenue through punishment.

At a time when the technology sector as a whole was taking off, e-carceration suited the moment. The discussion about alternatives to incarceration overlapped with the development of heightened GPS capacity, and investors began to eye electronic monitoring as a ticket to the future.

BI Incorporated, the Boulder, Colorado, firm that bought out electronic monitoring originator Michael Goss in the 1980s, was the leader from the outset, first cornering the market for radio-frequency devices, then pioneering the expansion of GPS tracking. The GEO Group, then the world’s second-largest private prison operator (it has since become number one), seeing the opportunity in e-carceration, jumped into the fray, buying out BI in 2009 for $415 million.(12)

Corporations including the GEO Group recognized that the addition of GPS capacity to ankle monitors didn’t just enhance authorities’ capacity to track location. As these devices got “connected,” they blended location-tracking information with data housed on the rapidly expanding mega-storage sites that became known as “clouds.”

Rather than remaining solely a tool of criminal legal policy, this foundational technology of e-carceration was becoming part of the surveillance state, a politicized system to aggregate and store data for transmission, retrieval, comparison, mining, trading and, of course, intelligence gathering.

The technologies of e-carceration, especially under the surveillance state, dehumanize in a unique way, transforming us from human beings to a collection of data points. In this world of e-carceration, we are no longer living, breathing beings or spiritual entities. Nor are we simply a case file or registration number as in the pre-computer, pre-internet days.

We become data points rendered on a screen, in an algorithmic formula, living not on the street or in a house but in databases or computer renderings of reality. We acquire a digital life of our own. In the words of Shoshana Zuboff, author of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, “both the world and our lives are pervasively rendered as information.”

But the power dynamics of this relationship often remain hidden. Zuboff provides us with an important wake-up call: “We think we’re searching Google. Google is actually searching us.”(13)

No comments:

Post a Comment