https://theintercept.com/2022/06/16/janes-revenge-abortion-rights/

The attacks on anti-abortion centers express a necessary militant fury. But the conflation of militance with violence is a mistake.

~~ recommended by collectivist action ~~

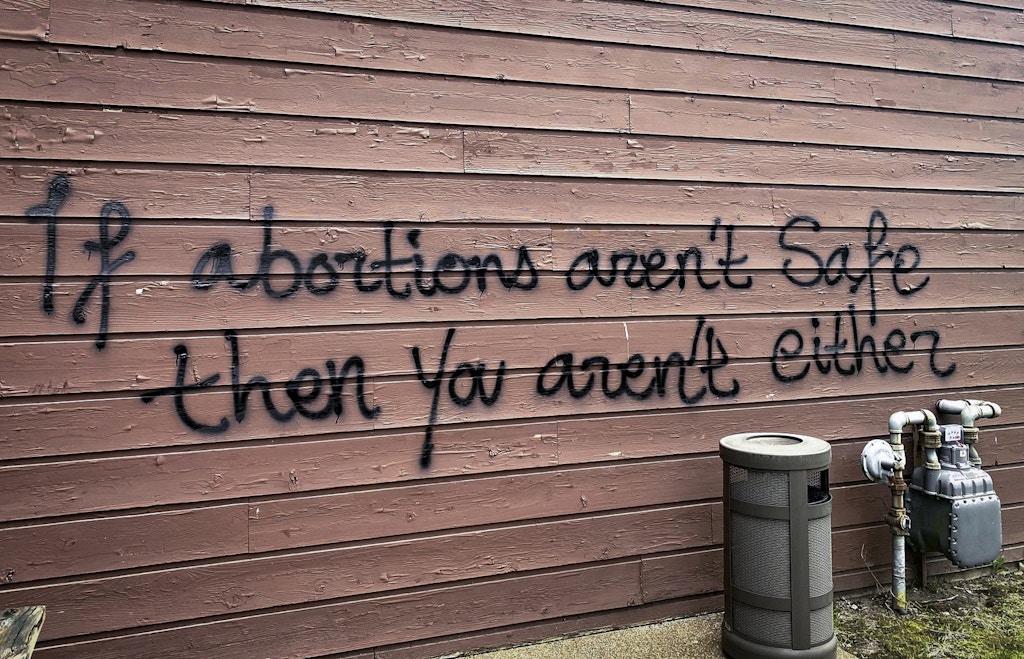

“If abortions aren’t safe then you aren’t either” is spray-painted on the exterior of a Wisconsin Family Action office in Madison, Wis., on May 8, 2022.

Photo: Alex Shur/Wisconsin State Journal via AP

WHEN I READ that a group calling itself Jane’s Revenge had firebombed anti-abortion “crisis pregnancy centers” in Madison, Wisconsin, Des Moines, Iowa, and other locations from Washington state to Washington, D.C., my first thought was: What the fuck?

Was this a false flag? Who but the extreme right, which had looked the other way while its terrorist armies murdered abortion providers, would besmirch the name of Jane, the Chicago collective that provided over 11,000 safe, illegal abortions before Roe v. Wade? This seemed the perfect tactic: A campaign of violence by pro-choice forces would reinforce the picture of abortion advocates as barbarians and justify draconian punishment of those who perform, facilitate, or have abortions.

Or was Jane’s Revenge a first — the anarcho-feminist descendant of the Weather Underground, the splinter of Students for a Democratic Society that bombed university and government buildings, banks, and other collaborators in the U.S. aggression against Vietnam during the 1960s and ’70s? The Weather Underground vowed to harm only property, not people. But inevitably, lives were lost to its botched heroics. Might Jane’s Revenge come to a similar end?

News coverage indicates varying skepticism. The mainstream media has mostly kept away from the story, while the Catholic press, the Washington Times, and Fox News were all over it. In the May 15 edition of his daily podcast, “It Could Happen Here,” Robert Evans, who covers extremism, reviewed the language of a communiqué from the group and the source through which it came to him, and expressed confidence that Jane’s Revenge is what it says it is, not some right-wing imposter. Evans called the acts “ethical terrorism” — the destruction of “infrastructure” rather than the “unethical terrorism” that targets “civilians” — agreed with a guest that the Wisconsin attackers’ bomb was a “pretty good Molotov,” and pronounced the action “competent” and its messaging clear.

Among abortion rights advocates, Jane’s Revenge — whoever they are — has gotten predictably mixed reviews. “Our work to protect continued access to reproductive care is rooted in love,” the president of Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin said after the bombing in Madison. “We condemn all forms of violence and hatred within our communities.” DSM Street Medics, a health care collective in Des Moines, tweeted a communiqué from Jane’s Revenge on June 9. DSM’s comment: “we are in no way affiliated with these actions, but we applaud them.”

My feelings don’t exactly jibe with any of these. When news of the bombings broke, like many Americans I was dragging myself around, heavy with fear and despair over the shootings in Buffalo, Uvalde, and Tulsa, the certainty that Congress would do virtually nothing, and the likelihood that the Supreme Court would worsen the carnage by ruling gun regulations unconstitutional. The threat Jane’s Revenge scrawled on the walls of the wrecked buildings — If abortion isn’t safe, you aren’t either — only increased my dread. Was this the next step toward a Hobbesian war of all against all?

Yet I confess: Their rhetoric speaks to me. The characterization of their targets is refreshingly unvarnished. Agape, in Des Moines, is a “religious fake clinic that inflicts emotional, financial, and physical violence on people who need healthcare and support. They lie to, shame, and manipulate people into not getting abortions.”

Their analysis is correct. The Uvalde elementary school shooting “was an act of male domination and patriarchal violence, meant to make women, children and teachers live in fear. We know it is deeply connected to the reproductive violence about to be unleashed on this land by an illegitimate institution founded in white male supremacy,” reads a call to action posted on the group’s website.

While the barely disguised call to violence scares me, the call to emotion nails the problem, and the start of the solution.

My rage and impatience boil as hot as theirs. I too am exasperated by the mainstream’s “demure little rallies for freedom” — the May 11 demonstrations left me more depressed than invigorated — and sick of sitting “idly by while our anger is … channeled into Democratic party fundraisers.” I thrill to their language — wrath, fury, ferocity — and to their declaration that “we need them to be afraid of us.” While the barely disguised call to violence scares me, the call to emotion nails the problem, and the start of the solution: “Whatever form your fury takes, the first step is feeling it.” Author and activist Alix Kates Shulman once spoke of the exhilaration of feminist outrage — “the outness of rage.” When Jane’s Revenge outed my rage, I experienced relief from an anxiety I didn’t know I was holding.

But now what?

We don’t know whether the Jane’s Revenge actions were coordinated or independent of one another. The communiqué speaks of “the desperate need for those who can get pregnant to learn how to confront misogynistic violence directly.” It urges that the “unlearning of our self-containment … begin in the streets.” Once you feel the fury, the group exhorts, “the next step is carrying that anger out into the world and expressing it physically.” How do we confront misogynist violence directly? How should we express anger physically? Aside from “learn by example,” Jane’s Revenge suggests a DIY approach to tactics.

And the strategy? Evans, the podcaster, says the messaging is clear — but I think he’s referring to the texts. What about the bombing itself? To whom does it speak? For whom is Jane’s Revenge speaking? Whom do they want to attract? Whom are they willing to leave behind? Violence wins some friends and loses others. Beyond striking terror in the hearts of the enemy, what is the end game? Is there an end game? To me, the message is not at all clear.

“Night of Rage,” the name Jane’s Revenge gave the June round of “crisis pregnancy center” bombings, is obviously an homage to the “Days of Rage,” organized by Weatherman in Chicago during the October 1969 trial of the Conspiracy Eight. The actions included smashing the windows of cars, shops, and restaurants full of patrons, hand-to-hand combat with police, and a planned invasion of a draft board office. The Days of Rage were a bust: The turnout was small, the cops overwhelmed the protesters, and the draft board break-in was foiled. In the end, the actions did little but further alienate Weatherman from SDS and the Black Panther Party, whose Chicago chair, Fred Hampton, denounced the faction as “opportunistic” and “adventuristic” dabblers in “revolutionary child’s play.” Weatherman was “leading people into a confrontation they are not prepared for,” Hampton warned. And indeed, October 1969 presaged the group’s descent into more reckless — and lethal — violence.

Kathy Boudin, one of the Weather Underground’s most charismatic and brilliant leaders, embraced the belief that the wars in Indochina and against Black and brown freedom fighters at home would not end without armed struggle. In 1981 she drove the getaway van for a robbery of a Brink’s armored truck, in which her accomplices, members of the Black Liberation Army, shot and killed a security guard and two police officers. The Brink’s robbery was probably not meant to be a fatal act. Boudin did not carry a gun. She was not even on the scene when the heist took place. Yet she went to prison for two decades, where she spent endless hours struggling to understand and take accountability for what she came to see as a hideous error.

Like the Weather Underground, Jane’s Revenge knows that its movement needs to become more militant. Yet it makes the mistake of conflating militance with violence. How can the movement for reproductive justice become more militant without escalating our tactics to mimic those of our opponents — without meeting violence with more violence?

How can the movement for reproductive justice become more militant without escalating our tactics to mimic those of our opponents?

An example can be found in the other inspiration of Jane’s Revenge: Chicago’s Jane Collective. As the beautiful film “The Janes” shows, the women of the collective gave every client compassionate, respectful, and assiduously excellent abortion care. Jane charged as much as the patient could pay, including nothing. When they decided to form Jane, most of women were already involved in civil rights, anti-war, and feminist activism. Some had taken physical risks, facing bottle-throwing hecklers in civil rights marches in Chicago or traveling to Mississippi on the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s Freedom Rides to register African American voters. What they were about to do was no trivial transgression: Abortion was a felony in Illinois, carrying a penalty of one to 10 years per charge. But they were frustrated with feminist politics as usual. Like Jane’s Revenge, they yearned for direct action.

The Janes performed a necessary service, but they did not consider themselves a service organization. They saw themselves as practitioners of nonviolent civil disobedience. “There was a philosophical obligation on our part … to disrespect a law that disrespected women,” said one woman interviewed in the film. Another member called helping a woman end her pregnancy and move toward reclaiming her own life “a revolutionary act.”

For Boudin, “the Brink’s truck incident and her arrest provoked crisis and transformation,” wrote Rachael Bedard in the New Yorker, but it did not weaken her commitment to radical social change, which she realized in service and organizing throughout her incarceration. When she was finally released in 2003, Boudin continued to work for justice, until she was too weakened by the cancer that killed her last month. “The lesson she learned wasn’t ‘I shouldn’t dedicate my life to the struggle,’” Boudin’s son, Chesa, told Bedard. “The lesson she learned, definitively and through tragedy, was ‘Violence is not productive.’”

No comments:

Post a Comment