~~ recommended by emil karpo ~~

The Pacheedaht people finally started making money from Vancouver Island timber. Then the protesters arrived.

PACHEEDAHT NATION, Vancouver Island, B.C. — The sweet smell of cedar sawdust filled the air amid the din of saws. In this tiny mill, not only boards but a bit of history was being made.

This is the first Indigenous-owned sawmill in Pacheedaht First Nation territory.

The People of the Sea Foam have long lived in this rainforest along the B.C. side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. For more than a century, the Pacheedaht have witnessed colonial extraction of the forests in their unceded territory. But now, they are reversing at least some of the flow of prime timber dollars back to their people.

The nation is getting a first-of-its-kind 50-50 profit split on logging some forestlands under a partnership created in 2018. And the nation is processing logs in its own mill, opened in 2017.

But a fight is underway over logging old growth forests, in the Fairy Creek drainage and beyond. Logging opponents and scientists are calling for these mature and old-growth forests to be set aside to help preserve biodiversity and combat the worst effects of climate change: extreme heat, drought, wildfire, flooding and more.

The conflict has Indigenous nations in the middle.

Publicity about logging blockades at and around Fairy Creek during the past two logging seasons is scaring off contractors the Pacheedaht would like to work with on new contracts that pay real money to the people, instead of the usual “beads and blankets” gestures, said Rod Bealing, the nation’s forestry manager.

“This is a really important opportunity for the Pacheedaht,” Bealing said. “And now this happens.”

On a patch of land that for some 100 years was a log sorting yard for the trucks rumbling in and out of its territory, the nation is operating its specialty mill, the equivalent in the timber industry of a diamond-cutting shop.

They mill only old-growth logs, with clear, straight, tight grain, sought for specialty jobs: trim, beams and bespoke boards for architects. Jeff Jones, elected chief of the Pacheedaht, said during a tour of the mill last fall that the new operation is “a dream come true.”

These forests under the new partnerships are generating revenue for the nation to pursue other economic development, from a community grocery store and gas station to tourism ventures and expanding its land base.

“Forestry is enabling the nation to buy its stolen land back,” Bealing said.

For all these reasons, the Pacheedaht do not support reductions in the availability of old-growth trees for logging.

The battle over old growth is pitting mostly non-Native activists against the Pacheedaht’s elected leaders and logging companies including the Teal Jones Group of Surrey, B.C., the largest family-owned, privately held timber company operating on Vancouver Island.

“We are really too busy for this crap,” Pacheedaht Chief Jones said of the protesters he and other Native leaders have repeatedly asked to leave. “They are not listening to us.”

The fight for what’s left

As the logging season returns this year, so does the fight.

Joshua Wright, a logging opponent from Union, Mason County, recently on social media put out a new call to action for this spring — including blockades on forests to be cut under Pacheedaht partnerships, beyond Fairy Creek.

“It doesn’t matter who cuts it, the result is the same,” Wright said.

Wright grew up amid industrial timberlands of the Olympic Peninsula and watched the big trees, birds and other wildlife disappear in a third round of clear-cutting trees harvested at 35- to 40-year rotations. “I’ve seen what it looks like when the land loses heart,” Wright said. By now, he said, he sees little around him left worth saving.

“It is one big cornfield, it has been homogenized to such a degree. It is not an ecosystem anymore, it is a farm.”

But the old growth of Vancouver Island has pulled him across the border over the past two summers.

Now 18, he is fueled by a sense that the trees must be defended. “I want to break down the notion that if a First Nation is cutting it, it is OK … Ultimately the biotic community and the climate still lose out. I don’t view it from a human-centric point of view.”

Bealing said Wright’s call for a renewal of blockades this spring, particularly in forests cut under the Pacheedaht partnerships, is “a direct attack on the Pacheedaht people.”

More than 1,100 people have been arrested during demonstrations and actions intended to stop the logging.

“Nobody is giving up,” Wright said. “The areas that still have those biological fortresses, they are the most important places in the world right now. It is about climate. It’s like this is a last moment.”

Vancouver Island’s forested landscape bears witness to B.C.’s colonial legacy of more than 100 years of logging. Today, 99% of the old-growth Douglas fir on Vancouver Island has been cut, according to the Ancient Forest Alliance, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving old growth.

VANISHING FORESTS

Outside Port Renfrew is a cut so stark, it has become a tourist attraction. People come from all over to see the infamous survivor, nicknamed Big Lonely Doug.

This giant fir tree towers amid a rising fizz of young trees, so tall at 226 feet, and so unimaginably large at nearly 40 feet around, it looks like something from another planet. And in a way, it is.

Big Lonely Doug sprouted about 1,000 years ago. That’s more than 700 years before the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, with its fossil-fuel burning that has stoked the atmosphere of our warming planet with carbon emissions.

Forests are key to moderating global warming because they hold so much carbon — about a third of all of our fossil fuel emissions are absorbed by the world’s forests every year. In a 2021 paper, 11,000 scientists from 153 countries warned the climate emergency poses a catastrophic threat facing humankind.

“When we look at what we are trying to do with climate change, protecting the mature and old forests is vital because of how much carbon they have in them, and they have stored it for hundreds of years, and they can continue to store it for 800 to 1,000 years,” said Beverly Law, faculty emeritus at Oregon State University and a specialist in carbon science.

It takes at least 200 years before a clear-cut forest even begins to approach the carbon storage of old growth, something scientists have known since research published in 1990 by Mark Harmon of OSU and Jerry Franklin of the University of Washington.

Franklin has continued his fight for old forests in the U.S., calling for an end to cutting mature natural forests in the western Cascades.

The climate emergency demands a moratorium on cutting old growth, Law said.

“We have to do everything we can to turn this around starting now,” Law said. “It is not saying, ‘We got ours, and now you can’t have yours.’ It is, we have an entirely different problem now, and if we keep harvesting, it will make it worse. It really is a crisis. It is severe.

“Nothing trumps climate change.”

Lucrative deals

In January, the B.C. Court of Appeal in a unanimous ruling extended an injunction against blockades or other actions that interfere with logging operations — virtually ensuring another season of clashes ahead between logging opponents and police.

“Protests are part of a healthy democracy; criminal conduct is not,” wrote the judges in their opinion. “… the injunction is all that stands between Teal Cedar (Jones) and a highly-organized group of individuals who are intent on breaking the law to get their way.” The judges also noted Teal Jones’ claim that $20 million in wood products were at stake from the Fairy Creek license area, where many of the protests have been concentrated.

Last year, Teal Jones deferred cutting within the entire Fairy Creek watershed for two years, at the request of the Pacheedaht and other First Nations, while they carried out a forestry planning process. But elsewhere within the license area and beyond, Teal Jones is pressing on with the cut this year.

Even big operators say they rely on old growth to make logging mostly younger trees profitable. Old-growth Douglas fir is worth more than 2.5 times smaller second-growth logs, according to Bealing.

“There are many areas where being able to go after a small percentage of that old-growth harvest makes the difference between it being economically viable or not,” said Conrad Browne, director of Indigenous partnerships for Teal Jones. “There are many times you can go after large swatches of second growth if you can go after a small percentage of old growth. It suddenly makes more sense.”

The company has been in business for 75 years, and has about 1,000 employees in B.C., including about 500 jobs at its Surrey mill site and headquarters, Browne said.

In addition to its B.C. operations, the company has five mills producing southern yellow pine lumber in Virginia, Mississippi, Oklahoma and Louisiana.

The company produces forest products shipped around the world, from lumber for construction, to Western red cedar shakes, shingles and timbers; custom cuts for high-end decorative use, and book-matched custom tonewood used for guitars.

“It’s always tough for industry to compete with people sitting around the fire strumming a guitar and singing Kumbaya,” Browne said. “Wouldn’t it be amazing to show them that the guitars they are strumming are made from the products we produce.”

For the Pacheedaht, it has been difficult to manage their forestry operations with confidence amid so much uncertainty, Bealing said. Proposed deferrals on cutting under discussion by the B.C. Provincial government in response to logging opponents also have upended the ability to plan.

A miserable border

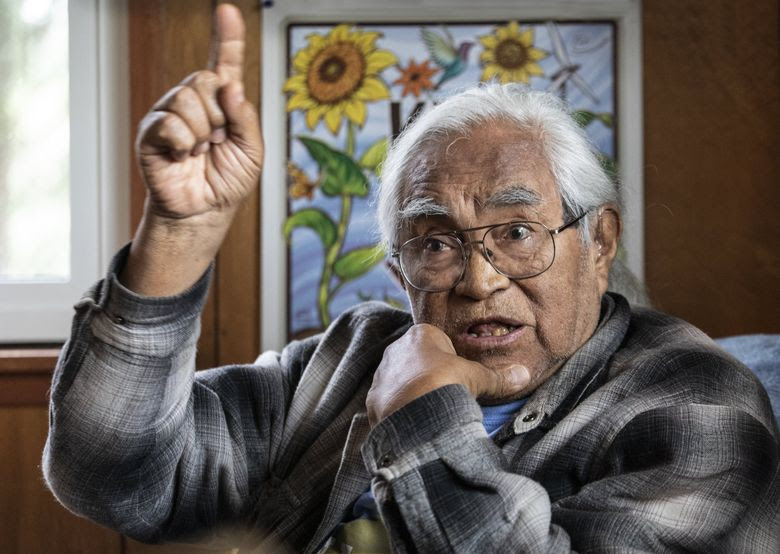

Elder Bill Jones has been the public Pacheedaht face of the logging opposition. He is 81, and isolated in his opposition, he said, with only a few other community members speaking out.

The logging blockades have not had much Pacheedaht support. “There are closet supporters, maybe six or eight, and there are a dozen or more half-supporters that need to be persuaded,” Bill Jones said. “But that’s about it.”

His silver hair swept back in a ponytail, he still wears suspenders like the logger he once was, setting chokers, one of the most dangerous jobs in the woods. He also worked as a boom man at a mill, balancing on floating logs to put the booms together for towing. “We were all tough loggers, my generation,” he said. “We all had the easy money, about 24 years of glory logging, and then it was all gone, at least the great volumes needed to support networks of papermills and logging and lumber mills.”

Now most of the big trees are gone — and he wants what is left protected. “The old-growth cedar — any old-growth tree, the older the better — mostly they are of spiritual value to me. They need to be prayed to, and talked to.” Values are crucial in this world right now, he said. “To be sane in this world now, you have to have your values holding you together.”

Elder Bill learned to honor the forest from his grandfather. “He told me you go up there, you pray, you meditate. You don’t ask for nothing and you don’t think. Our relationship with the forest is subconscious and subliminal. The forest is our owner. We are part of the old growth. Our Great Mother made the old growth, and she made us.”

He fondly called the protesters who have adopted him as their leader “eco-freaks.”

“I think the kids have imprisoned me. I was an old guy, watching TV, preparing to die.” He seems a reluctant leader, quick to note his own shortcomings.

“They refer to me as their elder. I reflect and magnify their values. It is almost humiliating,” Jones said. “I have a twinge of shame because of inadequacies that I think I have as a leader, that I am not fit to be a person of spiritual guidance.

“But I think the only real trait I have developed is honesty. And seeking the truth.”

The conflict couldn’t get more personal in this small community.

Chief Jeff Jones and Elder Bill Jones are relatives. They lived right next door to each other. “It’s like there is a wall, a miserable border,” Bill Jones said of the grassy swale between their homes, before he recently moved to an assisted living facility in Sooke.

“I am dead against logging of old growth and I don’t care who I offend saying that. I renew the fight,” he said as spring approaches.

As the controversy continues, so does life in the village at Pacheedaht, as it has always had to. Not far from the sawmill, the canoe from the giant log cut on Pacheedaht traditional territory was taking shape, as Micah McCarty, master carver and former chairman at the Makah Nation, made cedar chips fly with an adze.

The log was 30 feet long and 4 feet across. McCarty counted 38 growth rings to the inch. That’s a lot of years.

The Pacheedaht and Makah, across the water on their reservation on the Olympic Peninsula, are closely related and speak the same dialect of the Nuu-chah-nulth language. “It’s bringing our community together, to work toward a vision, and sharing pride,” said Pacheedaht council member Tracy Charlie, who came over to watch the carving. “It was the vision of bringing culture back.”

No stranger to controversy, McCarty also was the Makah Nation’s first whaling captain in 1999 when the Makah sought to resume hunting gray whales after a more than 70-year hiatus despite opposition by outsiders.

So the Pacheedaht are hardly the first small Indigenous nation to find themselves in the middle of a media and activist storm. Once more, the people of this place are fighting outsiders. This time, in a battle for the last of what’s left on an island where outside of parks and other restricted areas, only remnants of the vanishing old growth forest remain.

No comments:

Post a Comment