https://www.workers.org/2022/01/61106/

~~ posted for collectivist action ~~

Martin Luther King Day statement

Prisoners Solidarity Committee of Workers World Party

What does voting mean to an incarcerated person? As we honor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday in 2022, we consider this question within the context of the struggle for the right to self-determination for the most oppressed members of our class — particularly those who are incarcerated en masse within a system akin to modern-day enslavement.

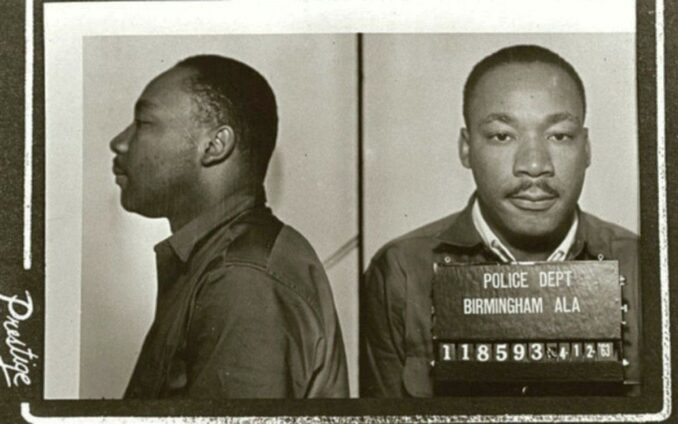

Rev. Ralph Abernathy, left, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. were arrested as they led a demonstration in Birmingham, Alabama, April 12, 1963. King’s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’ was written during his incarceration.

From a jail cell in Birmingham, Alabama, in April 1963, Dr. King wrote an open letter excoriating those who place demands on oppressed people who assert their democratic right to vote. He wrote that the “great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Councillor or the Ku Klux Klanner but the white moderate, who is more devoted to order than to justice, who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.” King rightfully viewed these moderates as apologists for fascist reactionaries.

Four years later, Dr. King’s April 4, 1967, “Beyond Vietnam” speech at Riverside Church in New York City forecast an even more radical evolution — from the right to vote to a worldwide view — when he linked the struggle for economic equality at home with the struggle against the U.S. war on Vietnam.

King spoke of how the U.S. government had violated the principle of self-determination for the Vietnamese people at the cost of growing poverty at home. He stated: “The security we profess to seek in foreign adventures we will lose in our decaying cities. The bombs in Viet Nam explode at home: They destroy the hopes and possibilities for a decent America.” His speech was condemned by both the Washington Post and New York Times.

It was this evolving political shift that ultimately marked Dr. King for assassination by the U.S. government, which he famously referred to as “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.”

Dr. King’s legacy

Remembering Dr. King’s political evolution challenges us today to consider the right to vote in relation to the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. It includes this language, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” (Emphasis added)

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’ — a germinal text of the Civil Rights Movement — while being held in solitary confinement, initially making notes in the margins of a newspaper. This is his police booking photograph in that 1963 arrest.

For those who find themselves in prisons convicted of a crime, they are literally treated as less than a whole human, as an enslaved person, not too far off from the days when enslaved people were considered three-fifths of a person when counted in U.S. populations for representation — but were not allowed to vote.

In many cases across the most incarcerated country in the world, known as the United States, this means imprisoned people are counted as part of the population wherever they are locked up, rather than in their communities of origin. But they are still unable to vote because of their convictions.

In Huntsville, Texas, there are seven prison units run by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. The population of that town, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, is 45,941. According to TDCJ’s unit directory these prisons — the Byrd Unit, the Ellis Unit, the Estelle Unit, the Goree Unit, the Holliday Unit, the Huntsville Unit and the Wynne Unit — have a combined total capacity to imprison 13,719 human beings; 13,719 is 29.9% of 45,941. (tinyurl.com/TDCJunitdirectory)

Imagine up to 30% of a population being counted in a census that determines how many resources are allocated to a given town for its elected representatives to spend. But that 30% is unable to have any say in who gets to spend that money or how. In many cases, these people are not from the towns they are imprisoned in — they have been ripped from their own communities and denied a voice in the so-called “democracy” where they live.

Black voters criminalized, disenfranchised

This voting disenfranchisement disproportionately affects Black, Latinx and Indigenous people as they are incarcerated at rates much higher than their share of the population. In Texas this has been true since the TDCJ was founded as the Texas Department of Corrections, as well as earlier under the system of convict leasing — often described as worse than slavery. (workers.org/2019/10/43909/)

Huntsville is also where the state of Texas has executed 573 people since 1982 — more than the next six states in the U.S. combined — and is a case study in why the racist, anti-poor and ableist death penalty needs to be abolished. (deathpenaltyinfo.org)

A 2019 study from Villanova University found that in Pennsylvania, where 40,000 people are currently incarcerated in state prisons, “[i]f prisoners were counted in their home districts during legislative map-drawing, the average Black Pennsylvanian would gain 353 new voters in their district; the average white person would lose 59, and an additional eight districts would be eliminated due to being either too big or too small.”

In that state, activists and reform advocates were able to force a major concession in 2021 when the Pennsylvania State Senate voted to end prison gerrymandering. Instead state prisoners now count as residents of the counties they lived in prior to incarceration. However, the state’s Legislative Reapportionment Commission later backtracked and said that this decision would not apply to those serving life sentences or sentenced to remain in prison until the next census — in 2030. That means that roughly one in four Pennsylvania prisoners still will not be counted as part of their home district. (WHYY, Sept. 21, 2021)

New York state Democrats put forward a similar initiative to prevent prison gerrymandering as a ballot proposal in November 2021. It was defeated along with other reforms including same-day voter registration and expanding absentee ballot access.

Injustice in county jails

While persons convicted of a crime are typically housed in prisons and are legally ineligible to vote, as in Texas, most of the people in county jails are locked up awaiting trial and are eligible to vote — but have no means to get to the polls.

Harris County Jail in Houston, Texas, is the third largest jail in the country. Like many jails around the country, upwards of 70% of the people inside are being detained pretrial and have not been convicted of anything. (Prison Policy Initiative, March 24, 2020, tinyurl.com/PretrialDetentioninJails)

Harris County Jail piloted a program to allow people arrested on or after Oct. 22, 2021, to vote in the November 2021 elections from a polling site located inside the jail. Volunteers from Project Orange, a group that helps register incarcerated voters, worked within the jail to help people arrested before that date to register for absentee ballots. Harris County Jail was the first jail in Texas to allow this to happen; a program was modeled somewhat on a pilot effort at Cook County Jail in Chicago in 2020.

These programs are rare, and while it is a leap forward to give incarcerated people access to their right to the vote, it is still a fundamental injustice that many of them find themselves trapped in jail due to their inability to pay bail bond while awaiting trial.

Beyond the vote — abolition!

More radical and deeper measures are needed. End the Exception, part of a movement to change the Thirteenth Amendment language, says: “In the last three years, three states have abolished slavery in their state constitutions. In 2018, Colorado became the first state since Rhode Island — the only state to have fully abolished slavery prior to the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment — to end the exception and abolish slavery. Following in its footsteps, Utah and Nebraska also led successful campaigns to abolish slavery in 2020. In all three states, the ballot initiatives were the result of unanimous, bipartisan legislative votes.”

Abolition of the afterlife of enslavement is the goal, and we aim to leave no member of our collective class — the working class — behind.

No comments:

Post a Comment