~~ posted for collectivist action ~~

Workers are going on strike and millions are resigning from their jobs. But we should not see the current and recent strikes in a vacuum or solely analyze the potential of these strikes by looking at the working class in its workplaces. This is only half the picture. There is a broader rupture, amongst working-class and oppressed people, with what was considered common sense in the neoliberal era.

“Deemed essential in 2020, proved it in 2021.” That’s the slogan on the shirt of a John Deere worker, one of 10,000 who went on strike for the first time in over 25 years.

And they aren’t the only ones. Miners, healthcare workers, carpenters, symphony workers, and more have all gone on strike in the past month. Even more workers have voted to approve potential strikes — tens of thousands of healthcare workers and tens of thousands of film and entertainment workers.

This is a rebellion of the “essential” workers who risked their lives and kept the economy running throughout the pandemic lockdown. Their bosses made huge profits and yet still refuse to give much more than empty words and pizza parties to celebrate these pandemic heroes. But these workers demand better.

We are also in the midst of the “Great Resignation”; in September alone, 4.4 million U.S. workers quit their jobs. That’s about 3 percent of the workforce. These workers, many of whom are unorganized, are also demanding better.

As supply chains are strained and job vacancies create problems for the entire economy, the working class is at center stage. Without a doubt, there is tremendous potential for the working class to build power now.

What is powerful about this moment is not just these labor strikes. After all, this isn’t a strike wave; unionization rates are at record lows, and the situation of the working class is still disorganized and dire. This is all true. But what is powerful about this moment is the combination of the strikes with the ideological shifts among working-class people and young people: the affinity for a vague notion of socialism, the anger at the bosses, last summer’s historic mobilization of the Black Lives Matter movement, and broad support for working-class struggle. This combination highlights ruptures in the neoliberal consensus among the broad working class, young people, and oppressed people.

But there are multiple forces that seek to contain and repress working-class power and self-organization, and to prevent these strikes from spreading and becoming more combative. There are many barriers that keep workers from seeing that their struggle is not about one workplace or one boss, but a struggle of an entire class against an entire class. As I will explore in this article, in this moment, although the working class is “center stage” and has found increased leverage and consciousness, the union bureaucracy and the Democratic Party have effectively contained worker’s discontent. Socialists have a role to play in pushing the labor movement forward and fighting each of these forces that seek to constrain working-class power.

A Working Class Shaped by the Pandemic

The current strikes are a direct effect of the pandemic on the working class. It’s hard to overstate the terror that large swaths of the working people felt: Would they get sick and die? Would they kill a family member? As one EMT said, “When you realize your boss will kill you, it changes your relationship to work” — and that same boss will make record profits in the process.

Throughout the pandemic, the working class organized several small actions, like healthcare worker protests or one-day actions by Amazon and Instacart workers. But the pandemic represented the lowest number of strikes in the past five years, as unions refused to organize the discontent into any major strikes, despite the unprecedented public support for essential workers.

The discontent from the pandemic was expressed in the spontaneous explosion of the Black Lives Matter movement, where millions of people around the country rose up to demand the end of anti-Black police violence, and many to defund the police. It was hard to miss that the police were decked out with up-to-date equipment to enforce curfews and attack protesters, when just a few months before, nurses had to resort to wearing trash bags to protect themselves.

But the pandemic changed the working class. If it wasn’t obvious to workers before, their essential role in the economy became clearer. As Marcos, a worker from Hunt’s Point Market who went on strike in January, said, “We kept this place open [in the pandemic], and a lot of guys died here. … While the bosses were home, I was here working for them. We are essential workers. They got money, they got millions. They didn’t share it with us. We deserve more.” This sentiment is echoed on every picket line in 2021.

Marcos is right. Capitalist wealth ballooned throughout 2020: the wealth of United States billionaires rose 70 percent during the pandemic, from $3 trillion to $5 trillion. Workers are watching this happen, and workers are pissed. People like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are widely reviled, and the myth that this system is fair is widely rejected.

But workers also know they have increased leverage and are “essential.” With strains in supply chains continuing to create problems for the economy, workers know that they move the economy and have the power to shut it down.

The Great Resignation

The supply chain crisis is only exacerbated by the Great Resignation. More than 4.4 million left their jobs in September, and 4.27 million left their jobs in August.

While bosses and the bourgeois press act as though it’s a great mystery why people don’t want to come back to work, the issues are clear. The problem is the terrible working conditions and the meager pay that have long plagued workers. Women in particular are dropping out of the workforce at record rates, many citing lack of childcare.

Some companies are reluctantly offering sign-on bonuses, and increasing wages in some sectors, especially for service workers. And yet, with inflation at over 5 percent, it’s too little too late.

Many of those resigning are non-unionized workers who see no path forward for a collective fight for better labor conditions at their jobs. And so they are quitting. In that sense, the Great Resignation reflects the very low level of unionization, which stands at only 11 percent nationally and only 6 percent in the private sector.

But it’s not just low-wage, nonunion workers who are resigning. Nursing and teaching, among the most unionized sectors, are experiencing historic shortages. One in five nurses have quit their jobs. In a recent survey from the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN), 66 percent of critical care nurses surveyed said they had considered leaving their jobs because of pandemic burnout and high patient-to-nurse ratios. And these aren’t new problems. Across the country, healthcare workers entered the pandemic overworked due to short-staffing, and the pandemic made conditions worse; many are quitting because they just can’t take it anymore.

These resignations among unionized workers highlight the complete failure of union leadership to fight for better labor conditions — not only now, but for decades. They are an expression of the weakness of organized labor. They are also an expression of individual resistance to the conditions of labor exploitation created by decades of neoliberalism.

But some workers aren’t resigning. They are going on strike.

Striketober, Stikesigiving

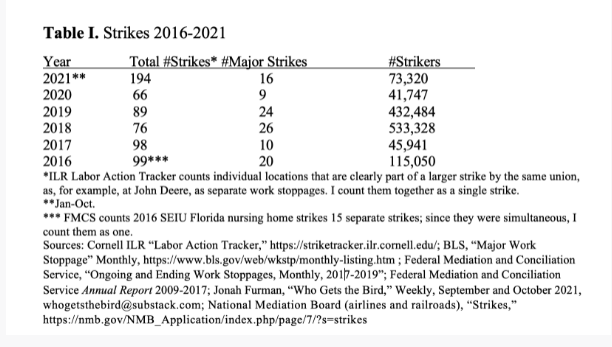

Capitalists who made a huge profit during the pandemic are drawing up contracts that include cuts to the salaries and pensions of the workers they cynically heralded as “essential” and “heroes.” For decades, union leaderships accepted austerity, cuts, and more precarious work conditions without a peep. But now striking workers are pushing back against the conditions imposed by the neoliberal capitalist system. They want more time off and a safe work environment. Many want higher wages, not only for themselves, but for those who will enter the workforce after them. According to Kim Moody, in 2021 there have been 194 strikes, the most in the past five years. These strikes, however, include fewer workers than in 2019, 2018, and even 2016. So there are more strikes, but fewer big ones.

In some cases, workers are fighting back against the two-tier wage system, which became an almost unquestioned staple of neoliberalism. The two-tier system means that anyone who is hired after the contract gets lesser pay and benefits. This is often a compromise with the bosses, sometimes supported by current workers, to maintain current levels of pay and benefits at the expense of future generations of workers. All too often, these Black and Latinx workers are the lowest tier. At Kellogg, this means $12 less an hour. At John Deere, it would have meant that new hires wouldn’t get a pension. For decades, contracts of this type have been signed by union bureaucracies in order to maintain labor peace, claiming that workers just can’t do any better. But workers at Kellogg, John Deere, and Kaiser Permanente understand that fighting the two-tier system is not only about fighting in solidarity for those with lower wages. It is about fighting a system that brings down wages for everyone.

These strikes have tremendous potential to win workers’ demands and inspire others to go on strike, creating a real strike wave. In the context of the supply chain crisis and Great Resignation, workers have even greater bargaining power. But already, union leaderships are calling off strikes, like at IATSE and Kaiser Permanente. And these strikes are a far cry from the radical strikes of the 1930s, or even from the more radical strikes we see all over the world today. Unlike in the most powerful strikes, the picket lines at Kellogg’s, Mercy Hospital, and John Deere are off to the side of their driveways — not actually blocking the entrance. Scabs go in and out relatively freely, maintaining some level of capitalist profit. The loss of that radical labor tradition shows on these picket lines, although there is potential to rebuild it.

Neoliberalism Crushed the Labor Movement

To understand both the disorganization of the labor movement, as well as the significance of the current strikes, we must understand the depth of the attacks on labor during the neoliberal era. This era was marked by attacks on the working class, increasing work hours and decreasing wages, ensuring ever-greater extraction of surplus value from workers. It was a reaction to the capitalist crisis of the 1970s and declining rates of profit, as well as the revolutionary uprisings of the late 1960s.

Neoliberalism entailed crushing unions and the labor movement: the U.S. went from 25 percent union density in the 1970s to 11 percent today. And the United States went from over 400 strikes involving more than 1,000 workers a year in 1973, to only five in 2009. In the United States, bosses found new ways to divide workers: contracts with two- or three-tiered wage systems were passed. Racist dog whistles were used to demonize low-income Black folks in order to bring down living standards for the entire working class, especially Black and Latinx people.

Neoliberalism resulted in a loss of wealth and wages in the working class and massive profits for capitalists. From 1979 to 2007, the incomes of the bottom 20 percent only rose 18 percent, while the incomes of the richest 1 percent rose 275 percent.

Rather than fight, union leadership convinced workers to accept wage cuts, no-strike clauses, and attacks on the ability to unionize while forging new shackles to the Democratic Party that further constrained the power of labor. They then put union funds and members’ energy toward electing Democrats who were implementing these same neoliberal attacks and called it putting up a fight for the working class. This is what Mike Davis calls the “barren marriage of American labor and the Democratic Party.” There was a radical shift away from almost any form of militant action, which resulted in a precipitous decline in strikes. Labor leadership’s almost exclusive goal became to act as an appendage of the Democratic Party, so labor militancy was off the table.

According to Stanley Aronowitz, the role of the union leadership is to act as “loyal lieutenants of the core capitalist and political institutions and their top players.” And this isn’t unique to the neoliberal era. Leon Trotsky explained that in the imperialist epoch of advanced capitalist development, union bureaucrats are representatives of capital in the labor movement. Antonio Gramsci explained that union leaderships play a central role in the “hegemony making” aspects of the capitalist state. In the neoliberal era, this meant ensuring the peaceful passage of attacks on the working class by pacifying class struggle and telling workers their power was at the ballot box.

The economic and political attacks on the working class involved profound ideological attacks as well. Put simply, as Margaret Thatcher claimed, “there is no alternative,” and people believed it: no alternative to capitalism, no alternative to accepting contracts that gave concession after concession to the bosses. Even on the Left, the ideological offensive undermined workers’ idea that they were society’s central agents of change and even revolution.

A Break With Neoliberalism

The 2008 economic crisis was a crisis of neoliberalism, and it has yet to be resolved. It created tensions “at the top,” among sectors of capital that have not come to a consensus about how to resolve the crisis, and struggles “at the bottom,” among the BLM movement, young people who favor socialism, and the working class, now re-emerging as an actor.

This shift was a long time coming. Starting in 2008, Occupy Wall Street highlighted massive inequalities, but on the whole it didn’t yet point to the working class. Later in the 2010’s, Bernie Sanders spoke out against the most glaring abuses of neoliberalism and talked explicitly about the struggles of the working class, yet he did so while funneling that energy into the Democratic Party. The shock of the Trump election in 2016 brought mass mobilizations, but no immediate labor response.

In 2018, the U.S. working class started a strike wave. Teachers organized illegal strikes in red states, followed by strikes in Los Angeles, Chicago, and Oakland, as well as strikes by General Motors and Stop and Shop workers. It was the biggest wave of strike activity since the 1980s.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13756349/chart.jpeg)

And the strikes came alongside an ideological shift: today, among workers under 30, 76 percent want to join a union. Among the general population, support is at 65 percent. This is a sharp contrast with the low of 48 percent support during the Great Recession. And instead of believing “there is no alternative,” young people are turning to socialism: favorability of socialism among Generation Z and Millennials is at almost 50 percent. The DSA ballooned in membership, standing at almost 100,000 today.

In that sense, we cannot see the current and recent strikes in a vacuum or solely analyze the potential of these strikes by looking at the working class in its workplaces. This is only half the picture. There is a broader rupture, amongst working-class and oppressed people, with what was considered common sense in the neoliberal era. There are, however, multiple barriers that seek to contain and constrain the labor movement.

The Law and the Bosses

Among the biggest barriers to strikes is the law itself. The law isn’t neutral, but on the side of capital. Many union contracts contain no-strike clauses, and there are laws against partial strikes that make the “secondary boycott” illegal. Even in recent strikes, court injunctions in Alabama and Illinois prevented more than four workers from standing together at picket lines at a time. Many laws, including right-to-work laws, also make it difficult for workers to unionize, introducing barriers like forcing them to essentially have two union elections, months apart from each other. And as Striketober and the Great Resignation show, non-unionized workers find it much more difficult to go on strike.

Bosses also engage in legal and illegal tactics to stop unionization drives. To stop unionization efforts, they force workers to attend anti-union meetings, and they spend millions on anti-union lawyers and consultants. At the Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama, we saw how Amazon even worked with the state to make workers spend less time at red lights so that they would have less contact with union organizers waiting at crosswalks to talk to workers during shift changes.

And to break strikes, bosses can use lockouts, where they hire replacement workers to keep workplaces running. Bosses also frequently use cops to break pickets, and the National Guard as strikebreakers.

Cops, bosses, and the capitalist state work together to deter worker organization, stop strikes, and, if necessary, crush and repress picket lines. But these barriers to worker organizing are not impenetrable or absolute: as one West Virginia teacher said recently, “Strikes are only illegal if you lose.” The state will always oppose workers — and so the working class must be prepared for this kind of fight, both in workplace struggle and in politics.

The Union Bureaucracy Stands in the Way

Union bureaucrats stand in the way of building working-class power, ensuring that labor struggles don’t become more radical, while funneling labor’s power into the Democratic Party. As noted above, these union leaders are the agents of capital within the working class and play a central role in limiting class struggle.

There are many recent examples.

Take the Hunts Point struggle in New York City, where on the first day of their strike, workers from a produce market blocked the street, confronting the police and making sure scabs weren’t allowed to enter the facility they were picketing. But the next day, union leaders were telling workers that this was a bad idea and that they shouldn’t “break the law.”

This Striketober, what would have been the largest strike, of up to 60,000 members of IATSE, was averted by undemocratic union leadership. While 98 percent of workers supported a strike, the union leadership agreed to a tentative agreement (TA) the day before the strike was set to begin. The TA does not address the workers’ most important demands, including ending the practice of 14-16 hour days with little turnaround time between shifts. The TA was ratified in an Electoral College–style vote in which the majority voted against ratification and it passed anyway.

But this isn’t a reason to stop working in unions; unions are still the largest organizations of the working class, and Striketober highlights that it’s unionized workers who have the most tools to fight back. But it is a reason to fight for internal union democracy: for unions that really are by and for the rank and file of the working class. As Rose Lemich explains, this includes assemblies to decide on demands, open bargaining sessions, elected and revocable bargaining committees and union leaderships, and more.

The Democratic Party is Not a Friend to the Working Class

As a party by and for capital, the Democrats represent the interests not of the workers, but of the bosses. The dire condition of the labor movement today is, in large part, a result of the attacks on labor power by the Democratic Party, despite their labor-friendly rhetoric. Joe Biden has carefully cultivated this image of himself as standing on the side of the working class for fear of workers siding with Trump in an “anti-establishment” vote. But we shouldn’t fall for it. The Democratic Party is the graveyard of social movements, as it was for BLM. And it’s the graveyard of a combative labor movement. Fostering the illusion that Joe Biden or any other Democrat is a friend of labor disorganizes the working class and sets up a barrier to building worker power.

Yet a whole sector of labor reporters and leftists are fostering those illusions. Jonah Furman of Labor Notes, for example, says, “We need a reverse PatCo. … This is the time for Joe Biden and the Democratic Party to step in, but on the other side. If we’re going to have a moment that signals to corporate America that you’re not just going to skate, that’s the course correction we haven’t seen yet.” A More Perfect Union echoes a similar sentiment in their article “The Most Pro-Labor President? Here’s What Joe Biden Must Do” — calling on Biden to “get involved” in the most recent labor struggles.

For authors like Furman, we “need” our class enemies to step in to tip the scales on the side of labor; the strength of the working class isn’t enough. This is precisely the insidious message that has always been peddled in the labor movement: that the labor movement needs the Democrats to “save us.” Furman is right that we do need a “reverse Patco.” But a real reversal of all the neoliberal and austerity measures promoted by the bipartisan regime should come at the hands of the organized and radicalized working class.

It is absolutely essential for workers to smash the tutelage of the Democratic Party and defy labor law by the collective decision-making of the rank and file. Our perspective should be to deepen the workers’ independent self-organization, which means learning to trust their united strength against the bosses and capitalists. This means defying and defeating the bureaucrats and their attempts to keep the working class subservient. It means learning that the government, including Biden, is against the workers.

From Strike to Class Struggle

Marx distinguishes between a class “in itself” and a class “for itself”: the difference between the existence of the working class as laborers and the working class united and in a struggle against the bosses and the capitalists. Lenin goes on to explain more deeply what this means:

When the workers of a single factory or of a single branch of industry engage in struggle against their employer or employers, is this class struggle? No, this is only a weak embryo of it. The struggle of the workers becomes a class struggle only when all the foremost representatives of the entire working class of the whole country are conscious of themselves as a single working class and launch a struggle that is directed, not against individual employers, but against the entire class of capitalists and against the government that supports that class.

These strikes over the past two months are, indeed, a weak embryo of the potential of class struggle. For the working class to become a class “for itself,” it must develop not only a consciousness about bread-and-butter demands but also a political consciousness. For class struggle to really be class struggle, it must unify working-class people against all the capitalists and the government.

The Role of Socialists

Throughout history, socialist workers have played a key role in labor upsurges and uprisings. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) coined the term militant minority to talk about the vanguard of class struggle, and it has been used to describe the socialists and anarchists who organized combative picket lines, defense committees, and democratic decision-making bodies for workers.

More recently, militant minority is a term taken up by Eric Blanc in relation to the 2018 teachers’ strikes, highlighting that many DSA members were involved in organizing those strikes. This is a helpful term to the extent that a radicalized labor movement always needs a radicalized core to push the movement forward. Indeed, there are always “militant minorities” that emerge in every struggle. But a militant minority is not enough. Militancy itself is not enough.

“A class for itself” is a class that organizes as a political force to fight for itself — in a political party that fights for socialism, the only program that represents the working class “for itself.” We do not merely support class struggle but must put forward a perspective for the working class to really win. This means a political program to wrest control of society from the capitalist class and the capitalist state and put it in control of the working class and the oppressed. And it begins by seeing the connection between the labor bureaucracy and the state, and particularly between the labor bureaucracy and the Democratic Party.

Putting forward this kind of political perspective isn’t an individual task. It’s the task of a group of socialists, united in agreement around these key issues and prepared to fight for them. We need a socialist political party to organize the most left and most combative sectors of each struggle under a collective program against the capitalist class.

We need socialist politics and a socialist party.

And this political moment is full of possibilities. Not only are there labor struggles but also young people turning to socialism. To this new generation of socialists, the importance of the working class is clear. There are socialists who are playing a role in class struggle, as in the 2018 teacher strikes.

But the current U.S. Left is not up to the task. DSA, the country’s largest left organization, is not fighting for an independent workers’ movement, but rather to serve as an appendage of the Democratic Party. It shows up at rallies alongside the union leaders who signed two-tier contracts in the past, as they did recently at a Kellogg strike. And they use labor struggles as pressure campaigns to elect Democratic Party leaders or to pressure Democrats into signing onto the PRO Act. And one wing of the DSA has an economistic, or class-reductionist approach to class struggle — which refuses to connect labor struggle to the struggles of the oppressed.

Unity of the Working Class and Oppressed

A working class for itself must be for all of itself: it must include workers who face oppression as well as exploitation. It means standing for workers who also experience racism, sexism, transphobia, and other forms of oppression.

This is key for the success of any working-class struggle, since racism is used to curb working-class organizing. At the Nissan unionization effort in Mississippi, not only was white-supremacist literature given out by anti-union organizers, but the bosses also provided small privileges to white workers in order to divide them. The result: no Nissan union in Mississippi. It’s a story replayed throughout U.S. history. And this not only results in the oppression and hyper-exploitation of working-class Black folks and other people of color, but it also drives down wages for all sectors of workers.

The working class must build antibodies against management’s racist provocations. And the way to do that is to fight for the labor movement to take up the fight against oppression — to organize in the workplace, to push unions to take action, and even to employ workers’ strongest weapon: the strike.

This fight against tyranny anywhere must also include an international perspective — this is especially true for workers in the belly of the imperialist beast. This means workers understand that their enemies are not workers in Mexico or China but the bosses who exploit workers all over the world. It means rejecting the borders that serve to divide workers for the profits of the bosses. This is essential in the current strikes: Kellogg’s workers, for example, are demanding that their jobs stay in the U.S. and not be sent to Mexico. This could easily become the social base for xenophobia and Trumpism if workers do not see that their coworkers in Mexico are exploited by the same bosses that exploit them and that the tens of millions of dollars in profit pocketed by the bosses during the pandemic could instead be used to improve working conditions for all of them.

We see sparks of this within the working class. In support of the Black Lives Matter movement, the ILWU port workers shut down West Coast ports on Juneteenth, highlighting the power of the labor movement to fight for Black lives. They also went on strike against the Iraq War in 2008. More recently, Jack in the Box workers organized protests when the boss threatened to call ICE against the workers who were speaking up against workplace abuses.

A working class “for itself” knows that it is for all of itself — meaning it is for the diverse members of the working class, including people of color, immigrants, queer folks, and all oppressed people. A class for itself sees the bosses as enemies, and workers in other countries as labor siblings in struggle. Moreover, a working class “for itself” cannot be just “for itself” but for every sector beat down by the capitalist system, for every sector oppressed by the bosses that exploit the labor of workers and the system that profits from their sweat.

After the biggest mobilizations in U.S. history last summer, and as young people continue to turn to socialism, there are pieces in place that show potential for a working class that radicalizes and becomes a class for itself. But there is a clear necessity of a working-class, socialist organization to push what is now an embryo of class struggle to deeper, stronger class war against the bosses and their government.

No comments:

Post a Comment