1). “Christopher Tackett Followed The Money And It Led Him To Uncover Two Texas Billionaires Controlling Texas’ Far-Right Political Agenda”, September 26, 2022, Claire & Nichole interview Christopher Tackett, Behind the Ballot, duration of video 57:30, or of the podcast 51:68, at < https://gobehindtheballot.com/

2). “How two Texas megadonors have turbocharged the state’s far-right shift”, July 24, 2022, Casey Tolan et. al., CNN, at < https://www.cnn.com/2022/07/

3). “Deep in the Pockets”, Jul 30, 2022, Documentary Video by Christopher Tackett, CNN, duration of video 43:35, at < https://www.youtube.com/watch?

4). “The Campaign to Sabotage Texas’s Public Schools”, March 2023, Mimi Schwartz, Texas Monthly, at < https://www.texasmonthly.com/

5). “Inside the Secret Plan to Bring Private School Vouchers to Texas”, October 18, 2022, Forest Wilder, Texas Monthly, at < https://www.texasmonthly.com/

6). “How a Brazen School-Voucher Scheme in Texas Got Derailed”, February 14, 2023, Forest Wilder, Texas Monthly, at < https://www.texasmonthly.com/

Introduction: IMHO Texas has become the leading state in the country for producing extremist reactionary / fascist political and socioeconomic initiatives (of course we could clearly argue that Florida is the number one in this regard and that Texas is a close runner-up). Where Texas is far different from Florida is that, in its relative vastness, and in the isolated resource extraction peripheries that exist in parts of West West-Central, South, and North East Texas, extremely virulent Christo-Fascist movements, so-called churches, and leaders have time to develop and become ever more dangerous.

The core of Texas Urban areas and where most of the state's people live is in an area called “The Texas Triangle”, roughly demarcated by I-35 on the west, I-45 on the east, and I-10 on the south, though the urbanized areas spill out tens of miles outside of the 3 interstate triangle. The urban areas of Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio, and Austin are all located in the Texas Triangle. If you live and work in Texas and your company or governmental agency sends you to: West Texas; the Texas Panhandle; The South Texas Border area; to The huge region between West Texas deserts and the Panhandle, and the Texas Triangle; or to the Piney Woods of Northeast Texas you have been sent a clear message and that is: “Your career here is over, you are now banished to whatever horrific outpost we have sent you to, don't call us we'll call you (and don't hold your breath)”.

These two money men for Texas style Christo-Fascism, who are discussed in these articles, both come from one part of this huge weird backward area. Timothy Marvin Dunn grew up in Big Spring, Texas but has resided for years in Midland, Texas. There he is a major figure and funder for a right-wing school and some crazed reactionary church where he occasionally preaches. Big Spring is about 30 – 35 miles from Midland (described by commentators as the most reactionary community in the entire U.S., it is where George W. Bush grew up after his father and mother moved there from Connecticut, to pursue making a fortune in the Oil Industry and furthering Bush senior's ongoing surreptitious CIA asset career).

Dunn obtained a degree in chemical engineering from Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas. Texas Tech is the largest university in any of the banishment zones. Farris Wilks (and his brother Dan, who is less overtly political) both still live in Cisco, Texas; a small city east of Abilene, Texas and deep in the “ region between West Texas deserts and the Panhandle and the Texas Triangle”. They are members of a truly zany reactionary Church with bizarre beliefs, including that homosexuality and abortion are crimes that should be vigorously punished. Concerning the Church where Farris Wilks is the Pastor: “the Assembly of Yahweh (7th day) is a conservative Jews for Jesus type congregation (though sans Jews, d.m.). It teaches that 'the true religion is Jewish (not a Gentile religion)' and its members celebrate the Old Testament holidays rather than those related to the New Testament. The congregation considers the Old Testament historically and scientifically accurate. The congregation considers homosexuality and abortion to be crimes.” (See, “Dan and Farris Wilks”, Wikipedia, at < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

The Wilks brothers grew up poor and did not obtain the same level of formal education as Dunn. The Wilks Brothers and Dunn are all billionaires that made their money in the Oil Industry. They are now using that wealth to attack public education and any progressive beliefs and practices. They fall into the faction of the Christian Right known as “Dominionists” (look that term up, but I will post some materials that address “Dominionism” in particular in the near future). That is they want to take political power and force their backward and hideous beliefs using state power, including murder and other practices. They want to be in the position of controlling the entire state apparatus and to use it to persecute those they think are evil, sad to say they have made significant progress towards that goal.

Wilks and Dunn are motivated by the plan to take control of the "7 mountains" of influence in American Society (the mountains are Arts and Entertainment, Business, Education, Family, Government, Media, and Religion). Their belief system is inspired by the work of Rousas John Rushdoony, only they are more bloodthirsty and have made far more progress towards taking actual political power. The vicious views of Wilks and Dunn are shown in their own words in short clips in the video in item 3). “Deep in the Pockets”.

The three articles from Texas Monthly, items 4 - 6, look at a political struggle over the public schools of Wimberly, Texas and the surrounding area. Wilks and Dunn funded much of the partially successful attempt to take over Wimblerly ISD and to use it to promote the use of public monies to fund private schools (mostly of the reactionary Christian flavor). Wimberly is a bucolic upper middle class and upper class suburban community near Austin, Texas. Sort of like parts of Marin County near San Francisco. This is sobering reading, but it does stand out that even though the state and many local governments in Texas are overtly Christo-Fascist the state still has a lively journalistic effort. This is, of course, bolstered by massive urban populations that live in and around Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio, and Austin as well as other smaller urban areas. The state government is controlled by authoritarians, who constantly take measures to limit the ability of the state's urban populations to vote, to control socioeconomic or political policies that affect them, or any of a number of other ways that the state government interferes in the operations of local governments. But they cannot control the political or social opinions of the large urban population, at least not yet.

Christopher Tackett Followed The Money And It Led Him To Uncover Two Texas Billionaires Controlling Texas’ Far-Right Political Agenda - Go Behind The Ballot

Attention Mentions:

Chris: The Flag and the Cross: White Christian Nationalism and the Threat to American Democracy by Philip S. Gorski and Samuel L. Perry

Claire: Dopesick on Hulu

Nichole: The Bachelorette on ABC and Hulu

There’s big money behind the Texas Far Right, and it was Chris Tackett who exposed it. In this conversation with Claire and Nichole, Chris shares how he got his start in public life by serving on the school board for Granbury ISD and how what was meant to be a nonpartisan race became partisan despite the wishes of him or his opponent. That experience led him to follow the money trail in Texas politics and what he found was enlightening and frightening. Chris discusses the influence of money in politics and how it can make a few voices sound like many. He talks about the need for free and fair elections and how being consistent in his message lights the way for how he moves forward. This episode is a can’t-miss for anyone who wants a greater understanding of the relationship between money and politics in Texas elections today.

—

Nicole, thank you so much for joining us for this episode of Go Behind the Ballot. We are going to be jumping into our elections series. We’re going to talk about why elections matter, why you need to vote and things that happen behind the scenes that you might not realize. That leads us to our guest for this episode, who is Chris Tackett. He served on the Granbury ISD School Board and he has this mission to help people understand money and politics.

Money is so huge when it comes to elections. Money equals communication and communication equals votes. He tells us about how these two billionaires in West Texas, Tim Dunn and Farris Wilks, have funneled millions of dollars into local races and so few people know that this is happening. Nicole, what did you think of this talk?

You know how excited I was that we got the opportunity to talk to Chris Tackett. I can’t even tell you how much I’ve looked forward to this interview. He shines a light. He makes things clear that seem muddy and unclear and helps everyone to understand them. Also, he is an excellent follow on social media on Twitter. He takes the fight to the issues.

He also has a great YouTube Channel where he makes these videos that allow people to speak for themselves so that you, as the viewer, can make your own choices and decisions about what you’re hearing people say. I think that highlights who Chris Tackett is. A guy who is making the things that we wonder about and have unclear information about making those things clear and obvious. Enjoy, it’s a great one.

I’ll lastly add, Chris Tackett is one of those people who ran because he wanted to level up his public service. He cares a lot about having a healthy democracy. This is so important when we talk about elections that we have good competitive races. He shows how having these super-rich billionaires very much goes against that and why we need to be aware of it. As Nicole said, this is a great read and we hope you will all enjoy it.

—

Chris, to get us started, we would love to know a little bit about you. Did you grow up in Texas? How did you start getting a little bit more politically involved?

I’ll say I can’t claim being a Native Texan because I was not born here. That’s one of the rules, but my parents moved us here to Texas when I was in the 4th grade. I have been here for the better part of my life. I went all the way through school here. I lived in other parts of the country. I lived in Canada for a couple of years but came back in 2008 with my wife and two kids to raise said kids and try and be close to family because we’ve been gone for a number of years. When we moved back to Grandbury, Texas, in 2014, I made the decision to run for school board with the support of my wife.

I was fortunate enough to get to serve. I won the election. I served on the school board from 2014 to 2017, but while I was there, I got a different sense of what was happening in the state and politically, had a newly elected House Representative, Mike Lang, in House District 60, which is where Grandbury is a part of. Had told us on the school board and the superintendent that he was a big supporter of public education.

We said, “When you go to Austin, here are the things that we think you should look at and support. They will help not only our district but other districts around the state.” He said, “Yes, no problem,” and then he got down to Austin and voted the opposite on every single one of those issues. It got me digging in, trying to understand why. To me, the obvious answer was money. I went into the Texas Ethics Commission website, started pulling campaign finance reports and saw massive amounts of money going to this guy from a handful of people.

Mostly, a gentleman from West Texas named Farris Wilkes, who is featured very prominently in the CNN documentary, Deep in the Pockets of Texas. As I figured that out, I started making pie charts to help make it easier for me to understand how much of this is coming from a handful of people but also to help others. I posted it on Facebook. People saw and started asking questions about, “What about my rep because they’re not supporting public education or all these other things either?” I started doing the research for candidates all over the state. It eventually led me to create a website ChrisHackettNow.com.

I have continued since that 2016, 2017 window ripping the entire Texas Ethics Commission database, repurposing it, putting it into a format where it’s easier for me and apparently, lots of other people around the state to leverage. It’s bar charts, pie charts, graphs so that you can go in and search for what you want and see who’s funding the politicians. The other thing it does is it helps you see very quickly what the web of money is. There’s a handful of people pulling a lot of strings in this state. That’s the abbreviated version of how I got here.

Thank you for sharing that. We want to talk about your website and the CNN documentary, Deep in the Pockets of Texas, but to rewind a little bit. I’m curious about your family growing up. Did you folks talk about politics? Would you consider your parents political because you went on to become a school board member, which is an elected office?

We weren’t political. It was one of those, you hear the things like you don’t talk about religion or politics at the table. I wouldn’t say we were hard and fast in that space, but politics wasn’t something we dove into. I grew up with my dad coaching my baseball team and being involved. With my kids, I took that space. When we moved back to Grandbury in 2008, I was the coach of my son’s team and my daughter’s teams.

I ran the local sports association for baseball and softball. I was the president there for about five years. To me, that serves not only to my kids but helping other kids in the community. The transition to school board felt like a reasonable push and between my professional space in the business world and again, my love of helping kids. It felt like, “This is a great place, a nonpartisan space that’s about community.” Going through that election changed some perspectives about the nonpartisan nature of elections, at least in modern times.

Were you prepared for that or was that surprising?

It was surprising because we hadn’t paid that much attention to politics. We had lived away for a number of years, so some of the local elements of things don’t happen. We had seen the rise of the tea party locally in Texas and across the country. Seeing that had been a little confused about some of the things that were going on, but it was one of those. It was like, “That was all big politics.” It wasn’t local stuff.

When I said I was going to run for school board, I very naively tried to schedule time to speak to all the various community groups n Grandbury. It was the optimist club and the Kawanas and all of these groups. Including the local democratic club, the local Republican club and the things you start to learn that are happening in the local politics as you go through that process. It was eye-opening.

Was your run competitive? What was that experience like when you decided, “I’m going to throw my hat in the ring and run for this position?”

It was myself and one other person. After the fact, as you go through the election, the other person who was running against me was a good guy who was trying to do it for some of the same reasons I was, wanted to contribute to the community. It’s one, the wife of the state Senator who lives in Grandbury, had somebody pull my previous voting record. I had voted in a Democratic primary in 2012 and because of that, I was a bad guy.

This state senator’s wife completely funded my opponent’s race, gave all the contributions to him and tried to do everything they could through the party and others to say some very not nice things about me. Including started running in what had been again, nonpartisan races locally, school board, city council and things, started running ads in the paper, as we were getting ready that was not authorized by the candidate.

That said, “Republican for school board and his name and everything.” I countered with, “Let’s not play politics with kids.” My opponent, at that point, as soon as they started running ads in his name that were making it very partisan, basically put his hands up and said, “I’m not participating in this.” Big kudos to him because this wasn’t what he wanted. It was the local political machine trying to take over and run this.

It was a 55-45 race in the end. He and I talked at length after the fact about, “We were trying to, again, serve the community.” The people we see at the grocery store, the people we run into at our kids’ schools, the softball games, or the baseball games. We were both trying to do it for the right reasons, but the politics on one side overwhelmed things. Luckily, I got the opportunity to serve the community in that space.

Now I understand why you say it was surprising because it sounds like that came out of nowhere. Talk about a political awakening that you may not have asked for, but here you are. I also respect your opponent that you both remained true to your original reasons for even running. I love these conversations we’re having because so much of my skepticism and cynicism is getting challenged for the best. It’s moments like that that give me so much hope. I keep saying this. This happens every time, but people who want to serve the public exists. They are out here and they’re running for offices. It gives me a lot of hope and optimism. It’s going to be okay, but we also have to expose and shine a light.

Yes, it’s making me think. When you started following the money, was that with your race or was it later on that you started digging into the Texas Ethics Commission reports?

It was after. Honestly, I did not know who was funding my opponent because I didn’t even think to ask for campaign finance reports because it was like, “What the heck?” It was only years later that I was like, “I’m going to go ahead and request those to see what happened.” Again, it was years later that I started digging into the Texas Ethics Commission. Again, I knew I had to turn my stuff in when I ran for the school board to the local district office. That’s where I was turning in my campaign finance reports. At the time, I had no clue that those reports don’t go to Austin and get loaded into a database. I figured that’s how it worked. You’re running for a public office no matter what level and everything goes to a central spot.

When I started polling from Austin and you realize, “This is only state-level races. Anything that’s local is maintained in these local spaces.” That’s what triggered me to say, “I want to find my race and understand this.” I think that one of the things people don’t understand is if you want to follow money, there are different places you have to go to be able to draw a complete picture. If you’re talking about city council races, county commissioner races, basically, anything that’s county level or below. It’s all maintained at those local spaces.

It’s generally if you’re in a small community, it’s not electronic. It’s one that you’ve got a request via a public information request. You can’t hop on the website and pull it. When you do get those, even from some of the larger places, it’s not like an excel type file where it’s easy to manipulate. You’re getting a scanned version of what was filed. Being able to connect dots and seeing who’s giving what, it’s hard. It’s easier at the state level because you can get an excel sheet and start to run these things together but following the money in this state, which also has no campaign finance contribution with it? It’s crazy.

We got to highlight this. I’m going to repeat what you said because I want to make sure I’m comprehending. Statewide races, that information is shared with must be reported to the Texas Ethics Commission. All of that is held in Austin and it is available electronically. Is that also true?

Correct. Anybody can go search for it, whether it’s the file or ID or the name and you can find those reports.

Now they may not be shiny and pretty, you’re also saying. The information is there, but it’s raw data, let’s say. For more local races, like you’re saying for trustees, for city council, that information is still kept at the local level and by who? Which office?

It’s all about what the race was. If you’re talking about a school board race, the school district offices maintain it. If you’re talking about a city council race, it’s the city offices. If it’s a county commissioner’s race, it’s the county offices. Somebody could be giving in all three of those spaces, but you would never know it because you’re only requesting this candidate’s reports, which aren’t indexed. They aren’t electronic in a database-type format. People can weigh in with money in lots of different places.

This might be jumping ahead, but is there any legislation to change this system or any movement to make it easier for folks to understand where money is coming from?

There has been some legislation filed. It hasn’t gone anywhere in the last few sessions to try and put whether it’s campaign finance, contribution limits in place or centralizing all campaign finance records in one place. I think the reality is that the people in charge now control some of the levers of power in the state. They’re pretty okay with the way things work. The idea that it’s hard to follow the money and that people can write a million-dollar check if they want to make it easier for them to do some of the things they want to do.

It means you don’t have to necessarily connect with the people you represent because you can get checks from all over the place. That may not be the people who live in your district, who may not be the people who, again, if you run into them in the grocery store, you would have any connection with. Stuff has been filed, but it hasn’t gone anywhere.

Maybe that will change with the information that more people are hopefully getting about what’s happening behind the scenes. A phrase that you said that stuck out to me was the people in charge. I wondered who are these people in charge? Is it even our representatives? I feel like that leads into the CNN special, Deep in the Pockets of Texas. Can you tell us a little bit about that special and the two people who are at the top, maybe the actual people in charge?

Now, Deep in the Pockets of Texas is a documentary that CNN put together. It’s an hour-long documentary that dives into if you’ve been following me on Twitter or Facebook or anything over the last few years that myself and my wife have been trying to yell about for a number of years. There’s not to say that we’re the only ones.

There have been lots of other people trying to highlight this, but it dives into not only what’s been happening with money in Texas politics and that two billionaires out of west Texas, Tim Dunn and Farris Wilkes, have very aggressively been investing millions of dollars in each electoral cycle in challenging and trying to get their people elected to then advance their ideology broadly across the state.

They put millions of dollars in, win some elections, lose some elections, but the whole time, they’re moving the Overton window. That idea of the way we look at things, what’s relative, pulling it further to the right and the documentary does a good job showing with the perspective of people who’ve been inside the Republican political machine and seen it with how they’ve been either marginalized or pushed to the sides because they haven’t been doing what these two billionaires wanted them to do.

It gets to this idea of a handful of people who are pulling strings on a lot of the politicians we see across the state. It’s not just them pulling the strings directly with the people they have. It’s also impacting other legislators who will vote the way they want them to vote. Maybe they’re not told directly, but they know this is what the conservative space is looking for because they don’t want to get a well-financed challenger in a primary.

Even though you have somebody who may not be aligned with the Wilkes-Dunn group, they’ll start to vote that way to avoid challengers as they go forward. That moves our overall Overton window in the state into a much more conservative space. What I did love about the documentary is it talked about not only the what, which is the money and the connections and such. It dives into the why, which is some of the ideology that comes from these billionaires.

I think that’s an important piece. For the folks, as they watch the documentary because it’s such a well-done document. It’s the tip of the iceberg. In an hour-long documentary, you can only talk about so much. There’s so much more below the water line that they haven’t been able to dive into, but I hope as people see it, it makes them more open to listening to the rest of the story. I can’t recommend that documentary enough.

For anybody who follows us on social media, on TikTok, it went across all of our social media handles and talked about where you can find it because Chris has it available on his YouTube Channel. Perhaps you’re like Claire and you were able to find it on YouTubeTV, but it can be found and we can help you find it if it isn’t simple for you. There’s something that you said that I’m hoping you can dig into a little more about. You talked about the tip of the iceberg. I’d be curious what else I think is where are we going?

It’s not only the ideology because that’s the space that starts to get scary on the why they’re doing these things. It’s also that understanding that. Again, the documentary is focused at the state-level type races but the reality is they are pushing, whether it’s public education and school boards, city councils or county commissioner races. The ideology that’s fueling all of this is one that aims to control all levers of government.

It’s not at the state house. It’s not at a federal level. It’s also those races, that again, historically have been nonpartisan, but they want to control. To touch a little bit on that ideology that’s mentioned in the documentary, it’s seven mountains dominionism. You may have heard Christian Nationalism as a term that’s leveraged. It was what fueled January 6th at the US capital. Seven mountains is the engine behind it.

It’s this idea that there are seven mountains or seven pillars of society. If you can gain dominion and again, it’s a biblical term. Gain dominion over those seven mountains, you can take a nation. When you start to dive into those mountains, it’s the church, the government, the family, education, the media, arts and entertainment and business. Those are the seven. That philosophy is to drive control. It is to own all levers of power. Not at the top levels, but it’s in all aspects of society. That’s the push to get these people elected so that they can pass the laws via the government to impose their version of religion on everybody else.

You see it when you look at the public education space, the push to ban books, the ridiculous CRT dialogue, which you can’t talk about history in what happened. It’s this idea of, again, porn and libraries, bathroom bills, anti-transgender students being able to participate in athletic activities. It’s all of these things come back to this push to devalue what we see for public education in people’s minds to create fear so that they can start to deconstruct it.

It comes down to money that comes down to this push for vouchers. It comes down to this push, they want the ability to indoctrinate kids in the way they talk about our schools or indoctrinating kids now, which is not true. Their real goal is that’s what they’re shooting to do in that one space. That’s some of the play in one of those mountains.

There’s so much about this ideology that’s very upsetting, but the thing that makes me very frustrated is they want to prioritize these things that it takes us away from what matters. Nicole and I read an article that Texas Tribune put out about how rural Republicans are holding back the floodgate for school vouchers and school choice.

They keep saying what we need to talk about is school safety, but we can’t talk about it because, somehow, they’re taking all the attention away. It’s so frustrating because it’s like we have the grid that needs to be fixed. We have to fix our schools. We’re losing our teachers. Our road systems aren’t the best and yet, what do we talk about session after session?

Trivial things or harmful things at worst and yet, that’s what that’s happening. As the documentary reveals, these two billionaires have had such influence and it’s been very much in the dark. We appreciate that you and other people are finally, it feels like getting some light on this so folks can know what is happening. Do you want this to happen? I don’t think many of us do.

There are so many people who, “I don’t want to talk about politics. I don’t want to wade into this space or that space.” We’re honestly at the point where if people don’t start talking about some of these things, the things that you value in your life, the things that you want your kids to have, the opportunity, the diversity that many of us celebrate, some of those things will go away and a lot of the public spaces. I think that’s pretty tragic. People do need to plug in and start paying attention to what’s happening in our communities, in our state and broadly in our country.

Such an important point. I found myself as you were sharing with us about the seven mountains, dominionism and philosophy and I watched your video, which was amazing. Here’s another plug for a Chris Tackett video. Here’s what I appreciate about your channel, which is that you don’t put commentary over the information you present. You allow people to speak for themselves, which means me, as a viewer, get to make my own choices and decisions about what they’re saying.

That is something that I appreciate. That’s one thing I want to say. I’m trying to make sense of it in my mind still. It’s like I can understand it on an intellectual level but what I’m trying to understand is like, if I were a believer in the seven mountains philosophy. If that was a rule that I lived my life by, I struggle and I don’t think anybody can answer this for me, but I feel the need to pause and say this.

I struggle with why there is such a deep desire to impose that on others and I get that it’s built into the philosophy. That it’s part of the thinking that it is your biblical duty to have dominion that’s part of what God has called you to do. Anyway, before we got on, Chris, I will also say I was watching another one of your videos. Maybe I won’t even get into the actual content of the video as much as to say there’s this scarcity also like mentality underneath it all I think that I find disturbing, which is this idea that only a certain thing can exist.

There’s a very specific way of life that is endorsed by them or that is put forth by them. Anything that is outside of that specific way of life, there’s no room for it. There’s no actual tolerance for anything that falls outside of this very specific way of living and philosophy. For me, the part that’s the most upsetting and disturbing is how narrow and specific and limited it is. Underneath it all is this idea that nothing else can exist because anything else takes away from their pie. It’s a real killer for me.

The reality is that you’ve had groups that have been marginalized. People who have not had that equal seat at the table and no one’s advocating that someone has to lose their seat. It’s, “Let’s make room for somebody else and somebody else’s voice and somebody else’s experience.” I went in South Beto’s Peak in Fort Worth.

He said, “It’s the philosophy we see from a lot of folks is you or me and rather than you and me.” That truly resonated with me as I was thinking about the things that we’ve been trying to talk about and what you articulated in what you’ve seen. It’s it is very much a you or me. It is not someplace that they can make room for anything that is different.

It makes me think in the documentary, there’s a woman who’s speaking and she is a theologian. It’s interesting because it comes down to theology. Do you believe in Genesis 1:28 to be interpreted that we’re supposed to have dominion over the earth and their sense of it, this domination? She’s saying not necessarily. It’s so frustrating that their theology is leading our policies when not even theologians are on the same page with this issue. We are the ones that they’re mercy, it feels like.

Without realizing it too.

Sure, because it’s all happening behind the scenes where we don’t understand who’s funding the politicians, who’s funding the packs. One of the things that I always touch on when I do my follow the money presentations is until you understand that when you go through a primary cycle and you’re getting ten pieces of mail in your mailbox every single day from all of these different groups. Until you realize that it’s the same handful of billionaires who are not only funding the candidates who are sending you stuff but also funding the packs who are sending you stuff, who are also on the board of directors of the nonprofit organizations who are sending you stuff.

It’s the same handful of people influencing so much of what we see in our politics in this state. Again, it’s not just Texas. It’s carried further, but it’s one for a low information voter when they see all of these mailings come in from these groups that have these names that sound like something you would want. Responsible government, “Yes. We want this.” Physical responsibility, yes. We should be physically responsible. Those things, you can get lulled into this space of, “This is a candidate I should be supporting,” because look at how many others are supporting them when the reality is, it’s the billionaires who have an ideology that they’re trying to advance. People don’t know.

Incredibly smart. It is very skillful to split that up into so many different entities that it feels like this is much bigger than it is.

Its voices being converted into a chorus. It’s not real.

That was probably my biggest takeaway from this documentary because I had seen you speak and you shared a lot of this amazing information. I had no idea how coordinated it was with these two billionaires giving to things like Texas right to life, Texas public policy foundation, the scorecard thing, defend Texas Liberty. I was like, “This is unreal.” It seems like you’re saying on its surface to be another group. It’s a nonprofit. Like, “This person’s got support and money and I’m getting these flyers. I’m going to vote for them,” but it’s all smoke and mirrors.

They try and present themselves as being grassroots, but they’re anything but.

What do we do?

That is the operative question. It all comes down to elections. It truly is about trying to make sure we’ve got people who believe in free and fair elections. We’ve got people who believe that a diverse society is a stronger society, who believe in public education, who, again, believe in LGBTQ rights, rights for the disabled, who believe in all of these things for separation of church and state. This is where getting people to take the blinders off and understand what’s at stake because all of the things I rattled off may not impact everybody’s life on a daily basis, but there’s probably something there. I didn’t even mention voting rights. That’s something that’s at risk too.

In any of those spaces, we have to help people understand what’s at stake and they have to show up in November. They have to show up in every election after that, whether it’s local or not or it’s a statewide or federal to make sure that we’re trying to put people in office who may not believe everything that you believe. There are almost no perfect candidates but trying to vote for people and help them move forward. That will represent the community that they’re supposed to be, therefore.

Whether it’s at the school board, city council, county commissioner, state rep, house rep, State Senator or the Governor’s mansion, we have to have people that truly represent us if we’re going to continue and continue to grow as a democracy, representative democracy. Whatever you want to call it but we have to engage. We’re like, what? Less than 90 days, I think, from the election at this point when we’re recording this. It’s now. We have to engage.

I was going to share with you all. When I was watching the documentary, one of the saddest moments to me and there were a lot of them. , the screen would go to black and the text would come up and say, “So and so is running in this election. They’re heavily funded by Dunn and Wilkes.” They don’t have an opponent. They don’t have a challenger. If I was someone living in these rural areas, seeing this documentary and I was like, “I’ll vote for the other person.” There is no other person in some cases. Can you talk about how that is damaging to our democracy?

In places like that, in the more rural spaces is where you especially see it happen. The activity isn’t in the general election. It is only in the primary. As we think about the redistricting process that we went through.

Which was sooner than it had to be.

We didn’t have all the information, and there were questions, especially about Texas, the numbers, and where things should have been. They did go through and redistrict and it was a very partisan push because there were a lot of districts across Texas that were competitive districts. That were leaning toward purple to where in the next cycle you could see some chick seats flip.

Districts were all drawn to basically maintain a status quo. Red districts got redder. They did draw blue districts bluer and created less purple. Less swing type districts with the idea of being, “As we go forward, we want to maintain control of those levers for any of these house races, these state Senate races.”

As it translates to the US House races as well, the congressional districts. It is to maintain the hold on power we have. What that does is in your districts that are those safe red districts like the one they talked about in the documentary because it is so red, there’s not a chance for somebody who’s a Democrat to win in that space. When you can’t win, it’s hard to get people motivated to run. To get the right people running for those.

It does take your politics ever further in an extreme direction because that’s who’s going to show up to vote. That’s the game that Dunn and Wilkes have played in very effectively over the last few years is taking those Republican primaries and making them more conservative, as the term I’ll use, all the way through. It hurts your democracy because you don’t get a balanced set of ideas talked about by candidates.

You don’t give the community broadly the ability to participate and influence who’s going to be representing them because there’s bad and worse, become your only choices as you’re going through this. To me, creating competitive districts where we will not be able to until the next census is completed. We’re plus years away from that next census starting, but competitive districts create dialogue in your communities. You will have what probably is the majority in most communities being able to make a real difference in that. You hear young people talking about, “It doesn’t matter for my vote. There’s no reason for me to vote.”

In certain districts, it’s hard to argue if you’re talking about an individual race because you can’t make a difference. You either may not have somebody on the ballot who represents you from your party or otherwise that’s out there. I think that’s where coming back to the issues at stake and understanding that whether it’s a local election talking about a school board or a city council or the bigger races, the statewide, Lieutenant governor, land commissioner, AG commissioner, governor’s race. You can make a difference in those races. It’s only by electing some of the people at a statewide level that truly represents us broadly. Will it enable us to get better people and more representative people running in these other spaces as well?

Yes, it’s like, I want to highlight to anybody reading who would consider sitting out any election that isn’t the solution no matter how defeated you might feel that your vote does matter. It matters even when it doesn’t feel like it. We can’t give up. Democracy is counting on every single person and every single vote.

To somehow find a way to encourage people to run even if they don’t win, but you never know if we’re going to win.

You might be surprised.

Magic could happen.

I believe in miracles.

That’s where finding good candidates who connect to their community should be supported. No matter which rates they’re running in. When you find good people, you support them and help them and shout their names from the rooftops in every single platform you have whether it’s online or in person. If you run into somebody at the grocery store, “Did you hear about this person’s running? They’re good. You should support them.” We all have to leverage our networks and, no matter where they are, to help these people make a difference.

I think also reminding people that when you run it, the wind can be something outside from getting that position. It can be Dunn and Wilkes have figured out, moving the conversation in the direction they want it to go. They have effectively done that by putting their money behind candidates who don’t even win. Their win rates like 50/50, but they’re getting what they want anyway. They’re getting people to move further to the ultraright. If we remind candidates, “You’re going to have a microphone,” and that is so valuable. If you can run for that reason, it could be worth the effort you’re going to put into it. It will hopefully help your community for the better.

I was thinking about how you said it so well, Claire, which is how can we redefine winning? In this case, I don’t even think what we’re talking about is a conservative versus liberal winning. What we’re all touching on is a democratic winning with a lower-case D. It’s what does a win mean in a democracy? It means having a conversation that is about issues that affect people. It means electing representatives who have your interests at heart and who will be responsive to you. That’s what the winning we’re talking about, having the conversations that we want to have.

As you’re saying, it does not have to mean that you win the office. It can mean at least having an agenda that is representative of the things that you care about and having conversations that matter to your community. Let’s focus on that. Redefining what winning means could be helpful. I know it’s shifting my brain because of that sense of defeat. If we could redefine like, “No, it wasn’t a defeat if we got to talk about these things that haven’t been talked about in forever.” Maybe some of the smaller communities that are unopposed races or whatever that picture could look like.

I would speculate, too, that this is what folks like Dunn and Wilkes are relying on. Tired of trying and trying that you’re like, “I got to step out and take a break.” What if no one’s there to pick up the baton then it’s game over. If we can find other ways to have our voices heard, maybe that’s the approach we should take until we can find a way to change the system the way they have. For some of our wrap-up questions, can you let us know what has been successful for you with your advocacy work? How have you managed to get people to listen to you?

It is be very consistent with message over and over. As I said, my wife and I have been beating this drum for a while now, a number of years. There are times when it feels like you’re screaming into the void. You’re putting this message out there. You’re trying to help people understand. It will get frustrating when you’re doing the advocacy work, when you’re trying to help people see things in a different way.

Sometimes it takes time and it takes lived experience in many cases, somebody feels personally, “Now I’ve experienced this. Chris, let me have a conversation with you because I have heard you talking about this. Is this what this was?” When you feel in your gut that something is right or something is wrong and you want people to hear about it. You have to be consistent in the way you’re talking about it. You have to figure out different ways to try and present it. I will tell you, the very first time I laid out the campaign information, the campaign finance numbers. I’m an Excel guy.

I had my spreadsheets and my numbers and I showed my wife the numbers. She’s looking at this Excel sheet and it’s like, “You’re not helping me here. You’re telling me this is awful, but I’m not seeing it.” It was translating those numbers into a pie chart that gave a visual, which is not the way I intuitively processed things, but it’s the way she did. It’s figuring out how you can share your message with people and how you can repackage your ideas in a way that may connect with someone differently.

It is truly that consistency of what we’ve done. I hate to say build a brand, but that’s where we’ve been because it has been not only the what is happening. That’s the money but touching on to the why. I would love to say, “We talked about this and this thing went away and therefore, it was a win and we didn’t get any attention for these things.” These bad things from our perspective continue to happen, it has helped others see it. They’ve had that lived experience and it has the things we’ve been talking about and other experts whom we’ve learned from along the way.

All of the work being recognized is helping people put into context the things they’ve been seeing happening all around them the scary things going on. That’s where coming back to the documentary for a second, what it did is distilled a lot of the things that we’ve talked about over the last few years into a single narrative. That, again, it’s not the whole story, but it’s a big piece of the story that made it digestible to folks.

I think that was hugely important in helping that message get out there. When they reached out and said, “Chris, would you be interested in being involved in this?” I was like, “Oh my gosh.” This is because we had made enough noise for a long enough time, someone referred them to us and it helped to create a different platform and a different way to go about it. Be the little engine that could. Keep pushing, keep putting it out there because eventually, somebody may notice and help carry your message even further.

Do you have any final thoughts before we move into our last little ending segment?

I don’t think I do. This is one of those that is going to be playing on my mind. I’m going to have all these things that I.

That’s what we do, back and forth.

Before we let our guests go, what we like to do is our attention mentions where we mention something that has our attention, like a show or a movie or an article, something like that. I’ll go first because I’m dying to share it because it’s so connected to what the work you do. I found this show. I don’t know how I missed it in 20201, but Dope Sick on Hulu. Have you seen this, Chris?

I have not seen it, but I’ve heard good things about it.

You got to go watch it. It basically tells the whole story of how oxycontin rose in the United States and the family behind it, the Sackler family. It was Purdue Pharma that created oxycontin and marketed very aggressively, got many people hooked on it and addicted. I think ha half a million people have died from it since it rolled out in like 1996. It’s amazing because they put the pieces together and they show you how this family was so skillful in marketing this drug and making it seem like these other nonprofit entities were pushing the value of it, but it was them behind the scenes funding these organizations. It was incredible. Very much recommend Dope Sick on Netflix.

I was obsessed with it for a little bit. When Claire said she was watching it, I was pretty excited. Do you have one, Chris?

I’ll say the book that I’ve finished reading, which again, relates to all of this craziness that we’ve been dealing with. It’s called The Flag and the Cross. It’s by Samuel Perry and Philip Gorski. It connects Christian Nationalism broadly and the things that drive it using social surveys, real outcomes on what we’ve seen to again help drive context. If anybody who’s reading what we’ve talked about here is intrigued and wants to dig deeper into the science behind the realities of what we’re seeing around us.

That book is a fabulous introduction, which again, if what we’ve talked about peaks your interest. Go look up The Flag and The Cross because they draw connections between the things going on in the Trump presidency. The things that we have all as people who care deeply about our communities have mobilized to go push back on. It puts real research-type information behind it to show you the root of the route that we see happening in these places.

It’s this idea of Christian Nationalism and the fact that these things that we’re all fighting are the weeds that come out of this one route. Until you understand that all of these things are being driven by different fragments of the same ideology, it’s hard to go fight. It will help people understand the mountain we were up against. Until you understand it’s a mountain, it’s hard to go fight.

It sounds like you could get exhausted because you’ll be exhausted finding that little bit of thing when you’re not focused on the bigger.

I can’t recommend that book highly enough.

Very cool. I wrote it down, but it also will be in our episode description. I’m going to take it in a totally different direction. I’m going to bring the lightness and the mindlessness. I have been watching the Bachelorette. They have two this season, which is a little bit chaotic and crazy. There are more tears than I think I’ve seen in a while on that franchise. It is mindless and it is a relaxing time when you need to like step out of the craziness. You can watch it on ABC or you can watch it on Hulu when it streams.

I’ll say the Great British Bake Off is that show for me.

I hear good things about it. My family watches it. I haven’t seen it with them, though.

They’re so and happy even when horrible things are happening in their kitchen in front of them.

Our brains need the time to let it go and get back up to fight. Thank you so much, Chris, for your time. We appreciate you chatting with us and sharing more about your journey with your advocacy and the incredible documentary that you are part of Deep in the Pockets of Texas. If you haven’t seen it, go check it out. Let us know what you think and follow Chris on social media to learn more.

How two Texas megadonors have turbocharged the state's far-right shift | CNN Politics

Gun owners allowed to carry handguns without permits or training. Parents of transgender children facing investigation by state officials. Women forced to drive hours out-of-state to access abortion.

This is Texas now: While the Lone Star State has long been a bastion of Republican politics, new laws and policies have taken Texas further to the right in recent years than it has been in decades.

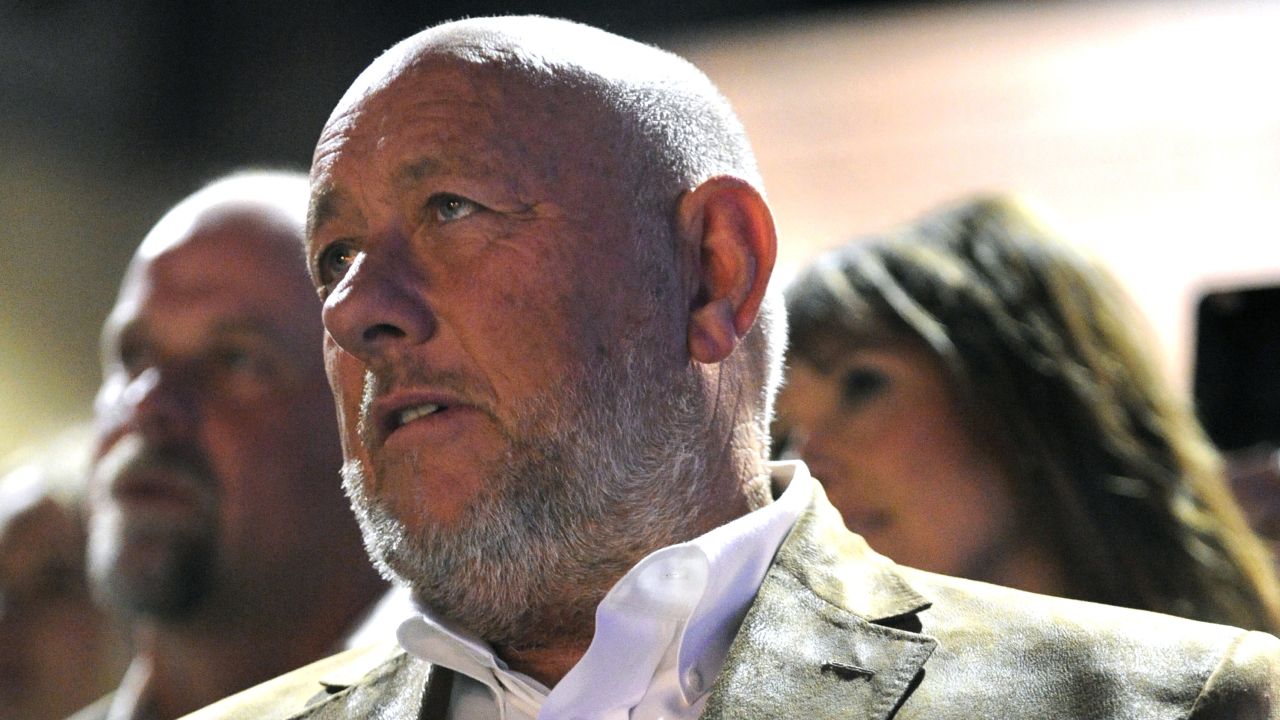

Elected officials and political observers in the state say a major factor in the transformation can be traced back to West Texas. Two billionaire oil and fracking magnates from the region, Tim Dunn and Farris Wilks, have quietly bankrolled some of Texas’ most far-right political candidates – helping reshape the state’s Republican Party in their worldview.

Over the last decade, Dunn and his wife, Terri, have contributed more than $18 million to state candidates and political action committees, while Wilks and his wife, Jo Ann, have given more than $11 million, putting them among the top donors in the state.

The beneficiaries of the energy tycoons’ combined spending include the farthest-right members of the legislature and authors of the most high-profile conservative bills passed in recent years, according to a CNN analysis of Texas Ethics Commission data. Dunn and Wilks also hold sway over the state’s legislative agenda through a network of non-profits and advocacy groups that push conservative policy issues.

Critics, and even some former associates, say that Dunn and Wilks demand loyalty from the candidates they back, punishing even deeply conservative legislators who cross them by bankrolling primary challengers. Kel Seliger, a longtime Republican state senator from Amarillo who has clashed with the billionaires, said their influence has made Austin feel a little like Moscow.

“It is a Russian-style oligarchy, pure and simple,” Seliger said. “Really, really wealthy people who are willing to spend a lot of money to get policy made the way they want it – and they get it.”

Dragged to the ‘hard right’

Dunn and Wilks did not respond to repeated requests for comment. In past interviews and opinion pieces, Dunn has argued that his political spending is focused on making Texas’ state government more accountable to its voters, while Wilks has described his donations as aimed at electing principled conservative leaders.

Former associates of Dunn and Wilks who spoke to CNN said the billionaires are both especially focused on education issues, and their ultimate goal is to replace public education with private, Christian schooling. Wilks is a pastor at the church his father founded, and Dunn preaches at the church his family attends. In their sermons, they paint a picture of a nation under siege from liberal ideas.

“The cornerstones of our government are crumbling and starting to come apart,” Wilks declared in a 2014 sermon at his insular church, the Assembly of Yahweh 7th Day. “And it’s because of the lack of morality, the lack of belief in our heavenly Father.”

Texas’ far-right shift has national implications: The candidates Dunn and Wilks have supported have turned the state legislature into a laboratory for far-right policy that’s starting to gain traction across the US.

Dunn and Wilks have been less successful in the 2022 primary elections than in past years: Almost all of the GOP legislative incumbents opposed by Defend Texas Liberty, a political action committee primarily funded by the duo, won their primaries this spring, and the group spent millions of dollars supporting a far-right opponent to Gov. Greg Abbott who lost by a wide margin.

But experts say the billionaires’ recent struggles are in part a symptom of their past success: Many of the candidates they’re challenging from the right, from Abbott down, have embraced more and more conservative positions, on issues from transgender rights to guns to voting.

“They dragged all the moderate candidates to the hard right in order to keep from losing,” said Bud Kennedy, a columnist for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram newspaper who’s covered 18 sessions of the Texas legislature.

“I don’t think regular Texans are as conservative as their elected officials,” Kennedy said. “The reason that Texas has moved to the right is because the money’s there.”

Political investments paying off

Over the last decade, many of the most conservative bills in the Texas legislature, on topics from LGBT rights to guns to private school vouchers, were killed by the moderate Republicans who held sway in the state House. That changed last year, thanks to people like Valoree Swanson.

Swanson was a Sunday school teacher and political activist when she challenged a 14-year incumbent Republican, Debbie Riddle, in 2016 in a district covering Houston’s Republican-dominated northern suburbs.

Swanson, who ran to Riddle’s right, shocked political observers by outraising the incumbent – an unusual feat for a first-time candidate. Her largest donor: Empower Texans, a political action committee created by Dunn and largely funded by him and Wilks. She defeated Riddle in the Republican primary by more than 10 percentage points and went on to easily win the general election.

Last year, Swanson won a major legislative victory: She authored the transgender sports bill, which blocks trans students from playing on K-12 school sports teams that aren’t aligned with their genders at birth. While other bills about transgender issues had failed in previous years, the sports bill was approved by a legislature now firmly controlled by the GOP’s right flank after the moderate former House speaker retired. Observers saw it as a validation of the billionaires’ early investments in Swanson’s first campaign, paying off years later.

“They’re effectively investing their money and they’re moving the needle on policy in Austin,” said Scott Braddock, the editor of Quorum Report, a publication that’s been covering the legislature for decades, referring to Dunn and Wilks. “These are extreme people investing a lot of money in our politics to reshape Texas, such that it matches up with their vision.”

Swanson is hardly an outlier: All 18 of the current Republican members of the Texas Senate, and almost half of the Republican members of the Texas House, have taken at least some money from Dunn, Wilks or organizations that they fund. Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick and Attorney General Ken Paxton have also been major beneficiaries of the billionaires’ spending.

Texas is one of just 10 states that allow individuals to make unlimited contributions to state political candidates, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures – letting Dunn and Wilks have more influence than they might elsewhere in the country.

While Dunn and Wilks focus on state politics, they’ve also gotten involved in national races. Wilks, his brother Dan and their wives were among the largest donors to super PACs supporting GOP presidential candidate Sen. Ted Cruz in 2016, contributing a total of $15 million. And Dunn has given millions of dollars to super PACs supporting former President Donald Trump and congressional Republicans in recent years.

In a statement to CNN, Cruz called the Wilks brothers “the epitome of the American dream” and “fearless champions of conservative causes, much to the consternation of the corrupt corporate media.”

So far in 2022, Dunn’s and Wilks’ political investments haven’t been as successful as in past years. Defend Texas Liberty, the group they fund, gave more than $3 million to Don Huffines, a former state senator who challenged Abbott in his Republican primary and won just 12% of the vote. Despite his loss, experts pointed out, over the course of the campaign Abbott embraced some of the positions Huffines had staked out, including strong opposition to transgender rights and support for deploying National Guard members to the US-Mexican border.

Defend Texas Liberty’s second-largest beneficiary this year has been Shelley Luther, an unsuccessful far-right legislative candidate who attracted national attention after she was arrested for refusing to shut down her Dallas hair salon to comply with coronavirus restrictions.

In an interview with CNN, Luther – who proposed banning Chinese students from Texas universities and declared she is “not comfortable with the transgenders” – said that Dunn and Wilks had been integral to her campaign.

“Without them, I couldn’t have even run,” Luther said. But she added that the spending wouldn’t have given the billionaires influence over her votes or decisions: “He wants me to do what I say that I represent,” she said of Dunn.

Enforcing the ‘law of the jungle’

Dunn and Wilks don’t just use campaign donations to play a role in state politics. They also fund a network of organizations that have been influential at boosting conservative causes.

Texans for Fiscal Responsibility, a non-profit chaired by Dunn, has released a “Fiscal Responsibility Index” each legislative session grading state lawmakers based on their stances on conservative bills. The scorecard, which is often cited in election ads that show up in voters’ mailboxes, is known in Texas political circles for its ability to make and break Republican primary campaigns.

“If you don’t show up well on the scorecard, you’re going to have a lot of money spent against you,” Seliger said.

Texas Republicans say that even a deeply conservative record doesn’t protect someone from a primary challenge funded by Dunn, Wilks and groups they bankroll.

State Sen. Bob Deuell had won elections for years in his northeast Texas district and racked up a conservative record – including co-authoring a 2013 abortion bill that was considered among the strictest in the country at the time, and was struck down by the US Supreme Court.

But in 2013, Deuell, a doctor, supported a bill that overhauled Texas’ end-of-life procedures. Texas Right to Life, a group whose largest donor over its history is Wilks, falsely claimed the bill would “strengthen Texas’ death panels.” The following year, Deuell was challenged by Bob Hall, a tea party activist.

Texas Right to Life spent more than $150,000 on mailers, voter guides and political consultants for Hall and other candidates in 2014, airing a barrage of ads claiming Deuell had “turned his back on life and on disabled patients.” Hall won the Republican primary in a runoff by 300 votes. Since that first campaign, Hall has received more than $900,000 from Dunn, Wilks, and groups that they are major funders of – about a third of his total donations.

“All this West Texas money is what made him into a viable candidate,” Deuell said of Hall, who did not respond to requests for comment from CNN.

Seliger, Deuell’s former colleague in the Senate, has also staked out conservative positions on many issues, and Dunn gave his campaign $1,000 during his first year in office in 2004.

But after Seliger decided he couldn’t support efforts to divert funding from public schools to private school vouchers, Dunn turned on him, he said. In the decade since, he’s found himself repeatedly running against a challenger backed by groups funded by Dunn and Wilks.

“That’s the law of the jungle now in Texas,” Seliger said. “The majority of Republican Senate members just dance to whatever tune Tim Dunn wants to play.”

Dunn has defended his spending and his group’s campaign tactics.

“Empower Texans remains outside the swamp, and the group informs voters who want their representatives to do in Austin what they promised during election season,” he wrote in a 2018 op-ed in The Dallas Morning News, responding to criticism of the group’s tactics. “If all of us outsiders stick together, we can drain the Austin Swamp.”

Zachary Maxwell has had an inside view of the billionaires’ influence. He worked for Empower Texans, Dunn’s PAC, and served as campaign manager and chief of staff for then-state Rep. Mike Lang, who received more than 60% of his campaign donations from Wilks and PACs he and Dunn were major funders of.

Maxwell told CNN in an interview that there was “no way” Lang could have gotten elected without Wilks’ money. At one campaign fundraiser, he said, Jo Ann Wilks handed Maxwell a check for more than $100,000.

“I was like, ‘Can you even write a check that big?’ ” Maxwell remembered. “I about had a heart attack.”

Huge sums like that helped buy Wilks influence once Lang took office, Maxwell said. “Whenever (Farris Wilks) called, he answered,” Maxwell said of Lang. “There was a lot of control.”

Lang did not respond to requests for comment from CNN.

West Texas upbringings

Texas has a long tradition of oil and gas magnates using their fortunes to shape politics. Hugh Roy Cullen, one of Houston’s wealthiest philanthropists, supported the pro-segregation Dixiecrat movement in the 1940s, and H.L. Hunt, who owned a vast swath of the East Texas Oil Field, funded a conservative radio program that aired across the US in the ’50s and ‘60s.

What sets Dunn and Wilks apart, political observers say, is how they’ve spent so much money pushing not just business-friendly policies that boost their bottom line but also socially conservative bills that seem designed to reshape Texas in the image of their far-right Christian values.

Both are products of humble West Texas upbringings who earned huge fortunes in Texas’ energy industry.

Dunn, 66, lives in Midland, the childhood home of George W. Bush and a center of the state’s oil industry. He grew up in nearby Big Spring, the son of a farm and factory worker, and studied chemical engineering at Texas Tech before working for Exxon and other oil and banking companies.

He started his own oil company, now named CrownQuest Operating, in 1996. The firm operates oil wells around West Texas’ Permian Oil Basin and beyond, and pumped 31 million barrels of oil in Texas in 2021, making it the state’s 12th largest oil producer, according to government records.

Dunn became more involved in Texas politics in 2006, when he opposed a tax measure that included a new tax on business partnerships – including some that fund oil wells, Texas Monthly reported. He started an organization to oppose the measure, Empower Texans, which continued to fund conservative causes even after the tax legislation passed. The group’s PAC shut down in 2020, and the billionaires more recently pivoted to funding Defend Texas Liberty.

Wilks, 70, grew up in a converted goat shed in Cisco, Texas, a town of 3,700 where sleepy streets are dotted with more than a dozen churches. He and his younger brother Dan were the sons of a bricklayer and started their careers as apprentice masons.

After several other business ventures, in 2002 they founded Frac Tech Services, a company that provided trucking services for fracking operators. It was perfect timing: Fracking was about to take off in Texas and elsewhere in the US amid a boom in shale gas.

Less than a decade later, in 2011, the Wilkses sold their majority share of the company for more than $3 billion to a group that included international investors. Since then, they’ve been buying up land in Texas and around the Western US, joining the ranks of America’s largest landowners – and getting involved in politics.

Farris Wilks is the pastor of the Assembly of Yahweh 7th Day Church, which operates a sprawling compound outside of Cisco and was founded by his father. In sermons, he has denounced homosexuality and abortion rights in vitriolic terms.

“A male on male or a female on female is against nature,” Wilks declared in a 2013 recording of one sermon posted on his church’s website, which is no longer publicly available. “This lifestyle is the predatorial lifestyle in that they need your children. … They want your children.”

Dunn also preaches at his church, the Midland Bible Church, where he serves as a member of the congregation’s “pulpit team.”

“No matter what rules you grew up with, none of them are enforceable in God’s kingdom,” he declared in one 2018 sermon.

In a 2004 interview with The Times of London, Dunn told a reporter he believed that, as the newspaper put it, “his oil has existed for only 4,000 years, the time decreed by Genesis, not 200 million years as his geologists know.”

That religious fervor has influenced Dunn’s and Wilks’ political moves. In a meeting with former Texas House Speaker Joe Straus, who is Jewish, Dunn declared that only Christians should hold leadership positions in the chamber, Texas Monthly reported. Straus declined an interview request with CNN.

And both Wilks brothers have donated millions of dollars through their personal foundations to conservative Christian groups, including crisis pregnancy centers, according to IRS records, which work to dissuade women from abortion and in some cases share misleading medical information.

‘The goal is to tear up, tear down’

People who’ve worked with Wilks and Dunn say they share an ultimate goal: replacing much of public education in Texas with private Christian schools. Now, educators and students are feeling the impact of that conservative ideology on the state’s school system.

Dorothy Burton, a former GOP activist and religious scholar, joined Farris Wilks on a 2015 Christian speaking tour organized by his brother-in-law and said she spoke at events he attended. She described the fracking magnate as “very quiet” but approachable: “You would look at him and you would never think that he was a billionaire,” she said.

But Burton said that after a year of hearing Wilks’ ideology on the speaking circuit, she became disillusioned by the single-mindedness of his conservatism.

“The goal is to tear up, tear down public education to nothing and rebuild it,” she said of Wilks. “And rebuild it the way God intended education to be.”

In sermons, Dunn and Wilks have advocated for religious influence in schooling. “When the Bible plainly teaches one thing and our culture teaches another, what do our children need to know what to do?” Wilks asks in one sermon from 2013.

Dunn, Wilks and the groups and politicians they both fund have been raising alarms about liberal ideas in the classroom, targeting teachers and school administrators they see as too progressive. The billionaires have especially focused on critical race theory, in what critics see as an attempt to use it as a scapegoat to break voters’ trust in public schooling.

In the summer of 2020, James Whitfield, the first Black principal of the mostly White Colleyville Heritage High School in the Dallas suburbs, penned a heartfelt, early-morning email in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, encouraging his school to “not grow weary in the battle against systemic racism.”

The backlash came months later. Stetson Clark, a former school board candidate whose campaign had been backed by a group that received its largest donations from Dunn and organizations he funded, accused Whitfield during a school board meeting last year of “encouraging all members of our community to become revolutionaries” and “encouraging the destruction and disruption of our district.” The board placed Whitfield on leave, and later voted not to renew his contract. He agreed to resign after coming to a settlement with the district. Clark did not respond to a request for comment.

Whitfield said he saw the rhetoric pushed by Dunn and Wilks as a major cause of his being pushed out.

“They want to disrupt and destroy public schools, because they would much rather have schools that are faith-based,” Whitfield said. “We know what has happened over the course of history in our country, and if we can’t teach that, then what do you want me to do?”

Meanwhile, the legislature has also been taking on the discussion of race in classrooms, passing a bill last year that bans schools from making teachers “discuss a widely debated and currently controversial issue of public policy or social affairs.” The legislation was designed to keep critical race theory out of the classroom, according to Abbott, who signed the bill into law.

Some of the co-authors and sponsors of the bill and previous versions of the legislation received significant funding from Dunn and Wilks.

The billionaires “want to destroy the public school system as we know it and, in its place, see more home-schooling and more private Christian schools,” said Deuell, the former senator.

The Texans feeling the impact include Libby Gonzales, an 11-year-old transgender girl living in the Dallas suburbs. She and her family say they feel like targets after the new law restricting trans students’ participation in school sports went into effect last year – passed by Swanson and other legislators bankrolled by Dunn and Wilks. Now, Libby won’t be able to play for the girls’ soccer team that she’d like to join.

“We don’t have issues in our neighborhood, among our friends,” said her mother, Rachel Gonzales. “It’s when our legislators meet and decide that they’re going to leverage their political power against some of the most marginalized kids in our state.”

Gonzales has started volunteering for political campaigns in an attempt to turn the tide on anti-trans policies. Libby said she’s been following the news about Texas’ conservative turn – and worrying what’s coming next.

Last month, the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a think tank that Dunn serves on the board of, called on the legislature to ban the prescription of puberty blockers and hormone treatments for minors.

“I’m under attack,” Libby said. “I have no idea why people don’t understand that I’m just a girl: an 11-year-old girl living in Texas – with amazing hair.”

The Campaign to Sabotage Texas’s Public Schools

What seems like an outbreak of local skirmishes is part of a decades-long push to privatize the education system.

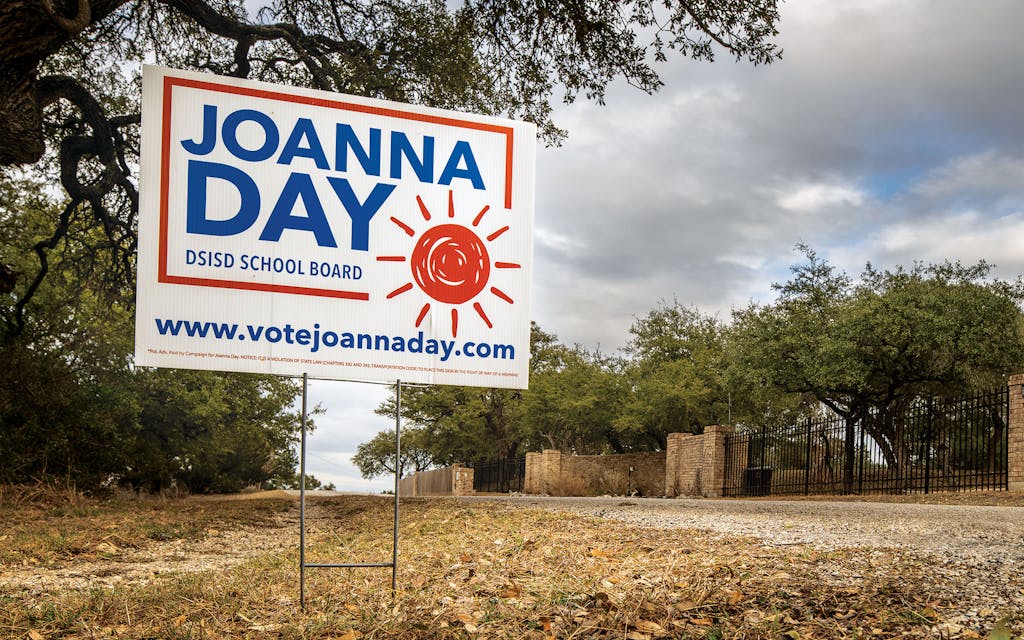

Joanna Day has never been a fan of horror movies, which is why she didn’t yet realize she was starring in one in real life. If you had to pick a turning point in her story, the part when everyone in the audience feels their jaws and shoulders tighten because they know—unlike the oblivious, trusting protagonist—that really bad things are about to happen, it would be when a member of the Hays County Sheriff’s Office showed up at Day’s home, in Dripping Springs.

It was a hot evening in August 2020, with the sun just about ready to give up on the day. The family was collected around the dinner table, which, thanks to its second-floor location, felt like it was in a tree house nestled in the branches of some comforting old live oaks. Day loved this house, with its rooms laid out every which way on three floors, the abundant windows filling the place with light. It was filled too with family: husband Eric, three towheaded children, two dogs, and all the accompanying detritus—kid toys, dog toys, books, and clothes dropped willy-nilly but in a good way, a happy way. Day’s indomitable optimism showed in the print hung in the stairwell with the famous Methodist maxim (“Do all the good you can by all the means you can”) and in the words on a multicolored abstract sculpture in the front yard (“Kindness can change the world one heart at a time”).

Tonight, as on most nights, plates clattered, silverware clinked, and the high-pitched voices of the kids—two boys and a girl, all under twelve—rose and fell as each competed to describe the best part of their day. “We only talk about the peak, not the pit,” is the way Day, 47 years old, describes this ritual. Focusing on the good calms the kids and fosters a positive outlook.

On this evening, though, the doorbell rang while someone was just about to get to their good part. Everyone went silent. The house sits high atop a hill on several brambly acres, a ten- to fifteen-minute drive from the middle of town. No one ever just showed up at the door, except the occasional Amazon driver, and he just tossed the packages and raced off.

The kids looked at their mom expectantly. Day pushed back from the table and trotted down the twisting flight of wooden stairs to the front door. When she opened it, a uniformed officer was holding her Lab mix, Heath, by the collar. Heath was panting proudly. How kind that he found our dog and brought him home, began Day’s internal dialogue. I have no idea how he got out.

But when Day focused on the officer’s words, she realized he wasn’t talking about the dog at all. He was young and blond and, she thought, unaccountably anxious. “We got a call about a domestic disturbance,” he said.

Now Day was confused. She didn’t know of any disturbance, except that with three kids, every day brought at least one. But rowdy children weren’t what the officer was talking about. Whoever had made the report, he said, “heard people threatening to kill each other.”

Day is a small, pale, brown-haired woman with a delicate, underplayed prettiness and a melodious voice. These characteristics can make her seem harmless, like someone who is maybe too nice for her own good. But before she became a full-time mom in Texas, Day was a public defender and an adjunct law professor at Catholic University of America, in Washington, D.C. She’d also taught in one of the city’s underserved public schools and lived a block away from an open-air drug market. Day had lingering fears about a stray bullet piercing the walls of her house. After she gave birth to her first child, in 2009, those dangers figured into her and Eric’s decision to move to Austin. Later, in 2015, they moved twenty miles southwest, to Dripping Springs, where ostensibly the biggest threats were fire ants and rattlesnakes.

But in the past few months, Day’s sunny life had grown dark. There had been phone calls with no one on the other end and Facebook posts in which her name was attached to lie after lie. Once friendly faces shunned her in the grocery store. And just the other day, someone had told her about a local troll doxing her on a neighborhood website, posting her home address. Now this officer was suggesting the danger was coming from inside her house?

After witnessing the quizzical faces of three clearly safe kids, the officer retreated. That’s when Day started fuming. She had no proof that the dinnertime disruption was related to previous threats, but logic suggested it was. Someone was trying to rattle her, and the reason seemed clear. Day had unknowingly made one big mistake after moving to town. In 2019 she had run successfully for the Dripping Springs Independent School District’s board, a job that not long ago had been about as controversial as cafeteria lady.

But that was then.

The scenes have become weirdly familiar all across Texas. Just a few years ago, furious, placard-waving parents protested pandemic-induced school closings and mask mandates. Now that anger has been redirected toward school library books that deal with issues of race and gender and toward the supposed teaching of critical race theory, a college-level framework for examining systemic racism that is not actually taught in Texas public schools.